Science

The Family That Walks On All Fours

Full article here.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Mar 03, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Human Marvels, Medicine, Regionalism, Science

Ballads for the Age of Science

The whole playlist is here.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jan 21, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Education, Science, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Children, 1960s

Noses

Read it here.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Jan 20, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Body, Science, Psychology, Self-help Schemes, 1950s

Captain Entropy

The creator's Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Dec 24, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Drugs, Education, Music, Science, Children, Bohemians, Beatniks, Hippies and Slackers, 1970s

The Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification System

In the early twentieth century, odor researchers Ernest Crocker and Lloyd Henderson created a classification scheme that allowed them to number and catalog every smell in the world. Kind of like a Dewey decimal system for smells. Every different odor was assigned a four-digit code.Their system was based on the premise that every smell is a combination of four "primary odors." So the four-digit code was created by judging and listing the relative strength of each primary odor.

The problem was that judging the relative strength of each primary odor in any one smell turned out to be a very subjective process. Other people struggled to replicate the numbers that Crocker and Henderson came up with. So their system was never adopted by other researchers.

More info: NadiaBerenstein.com

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 15, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Science, Smells and Odors

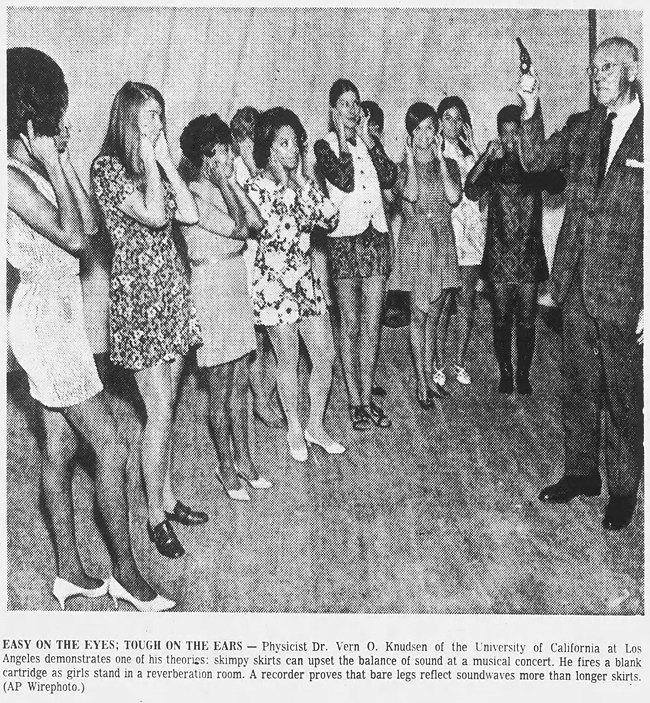

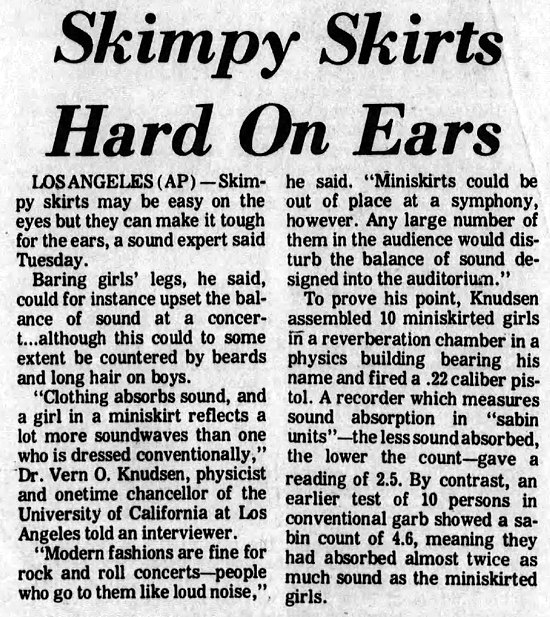

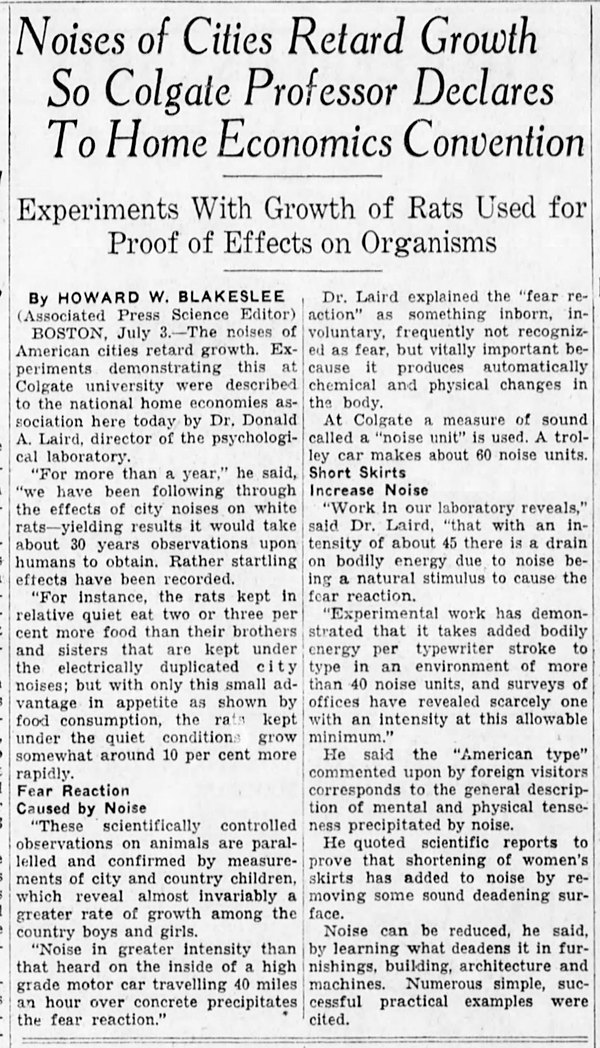

The Acoustics of Miniskirts

October 1969: UCLA Professor Vern O. Knudsen assembled ten young women wearing miniskirts in a reverberation chamber and fired a blank cartridge from a pistol. He did this to prove his hypothesis that bare legs revealed by a miniskirt will reflect more sound than legs covered by a long skirt.His hypothesis confirmed, he warned that miniskirt wearers might disturb the carefully engineered balance of sound in concert halls by reflecting more sound. He noted: "We must be acoustically thankful that they don't wear bikinis."

Rock Island Argus - Oct 29, 1969

Orangeburg Times and Democrat - Oct 29, 1969

Oddly enough, this wasn't the first time a scientist had warned of the acoustic danger of short skirts. Back in 1929, Colgate University Professor Donald A. Laird had issued a very similar warning: "He quoted scientific reports to prove that shortening of women's skirts has added to noise by removing some sound deadening surface."

San Bernardino County Sun - July 4, 1929

Related posts: Miniskirts for road safety, Nun in a miniskirt

Posted By: Alex - Thu Nov 03, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Fashion, Science, Experiments, 1960s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

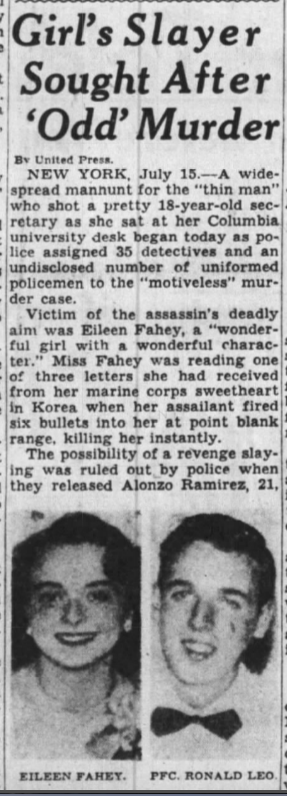

Unlikely Reasons for Murder No. 11

In 1952, a schizophrenic with an eccentric theory of physics murdered a random person.“Have they dropped the electronic theory?” he asked her.

“I don’t know anything about it,” she replied.

Before she could say more, he fired the gun at her.

“I just wanted to kill somebody,” he told police. “I was going to shoot anybody. It was my book. They wouldn't look at my book. They wouldn't even look at it."

Peakes had done the calculus: Shooting people gets you in the papers. And if you shoot physicists because they rejected your theory, your theory gets in the papers.

Full account here.

The initial coverage below.

Article source: The South Bend Tribune (South Bend, Indiana) 15 Jul 1952, Tue Page 1

Posted By: Paul - Wed Nov 02, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Science, Scary Criminals, 1950s, Mental Health and Insanity

One Step Beyond: The Sacred Mushroom

Here is the Wikipedia page for the show, which has a section on this episode.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Oct 04, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Drugs, Psychedelic, Science, Television, 1960s, Natural Wonders

The Palatibility of Tadpoles

In 1970, biologist Richard Wassersug conducted a study to determine what different kinds of tadpoles taste like. More specifically, whether some taste worse than others. He convinced 11 grad students to be his tadpole tasters.The most distasteful tadpole was Bufo marinus, while the most palatable ones were Smilisca sordida and Colostethus nubicola.

This confirmed his hypothesis that the most visible tadpoles were the least palatable. Their bad taste deterred predators from eating them, whereas the better tasting tadpoles relied on concealment to avoid being eaten.

Thirty years later, Wassersug was awarded an Ig Nobel Prize for this research.

More info: "On the Comparative Palatibility of Some Dry-Season Tadpoles from Costa Rica"

Richard Wassersug poses with a frog

image source: University of Chicago

Posted By: Alex - Thu Sep 29, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Science, Experiments

Can you speak Venusian?

In his 1972 documentary, Can You Speak Venusian?, the British astronomer Patrick Moore examined the astronomical theories of various "independent thinkers" — otherwise known as kooks. It's probably now the only footage of most of these odd folks, talking about their odd ideas. Moore released an accompanying book of the same name.My favorite of his independent thinkers is John Bradbury and his 15-lens telescope, viewable at around the 15:30 mark. His basic idea was that if two lenses are good, then fifteen must be even better. Bradbury claimed his telescope was so powerful that it could show "the actual background casing of the universe."

source: Can you speak Venusian?

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 13, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Science, Spaceflight, Astronautics, and Astronomy, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |