Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters

Atomic-Powered Vacuum Cleaners

Alex Lewyt, owner of the Lewyt Vacuum Corporation, has been mocked for his 1955 prediction that vacuum cleaners would one day be atomic-powered.But he also predicted self-guided, robotic vacuums, and he was right about that.

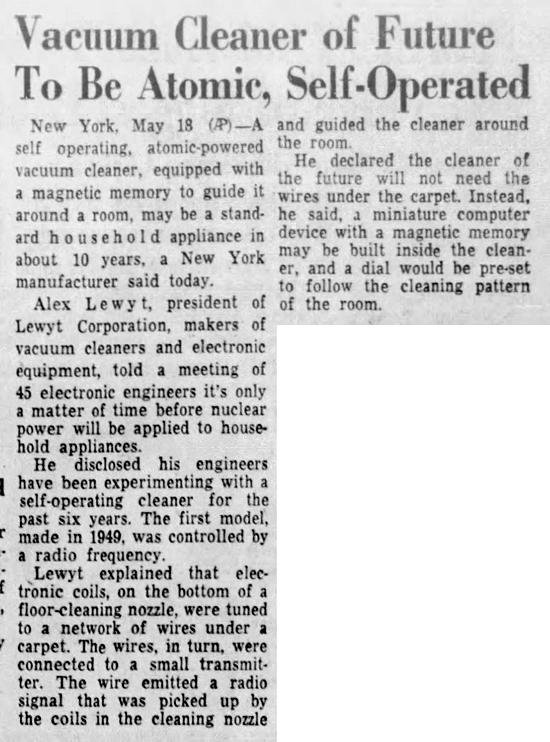

Louisville Courier Journal - May 19, 1955

Albuquerque Tribune - Jun 7, 1955

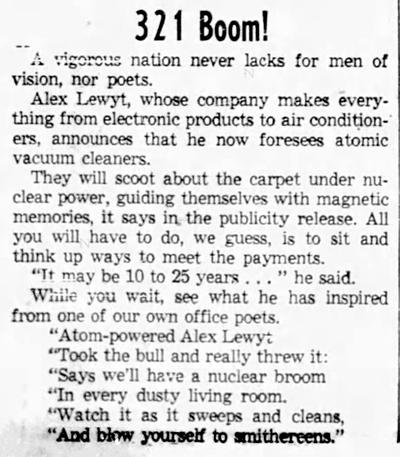

Below: a 1950 ad for Lord Calvert whiskey that, for some reason, featured Alex Lewyt. Note the vacuum cleaner in the glass case behind him.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 26, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, Appliances, 1950s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

The Atomic Balm prank

I'm not sure when exactly Atomic Balm was first sold. I believe it was sometime in the 1950s. But it very quickly became widely used by football teams as a pain-relieving ointment.It also became a favorite of pranksters. The prank involved surreptitiously placing Atomic Balm in a player's jockstrap. Since the ointment contains Capsaicin, the results were painful.

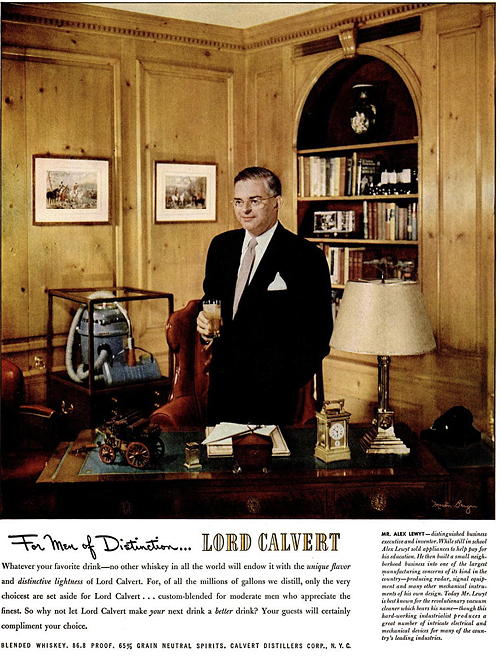

The Atomic Balm prank was a perennial favorite on high school football teams, but the most famous instance of the prank occurred on the Miami Dolphins, recounted below.

Source: Teena Dickerson, The Girlfriend's Guide to Football

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 19, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Sports, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, Pranks, Pain, Self-inflicted and Otherwise

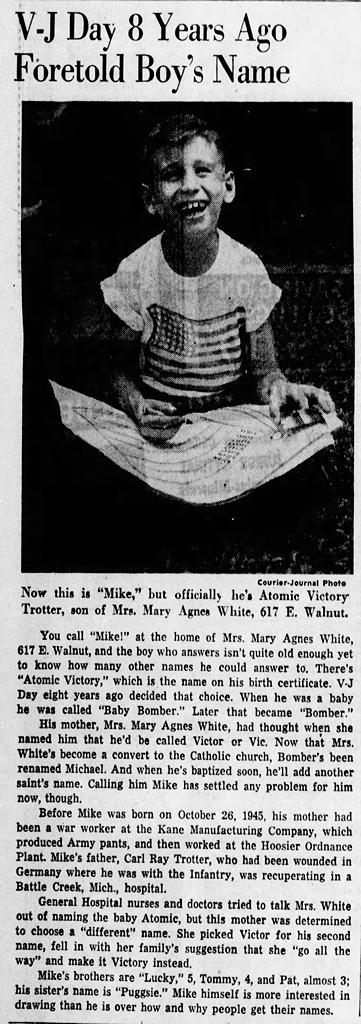

Atomic Victory Trotter

Seems that everyone called him 'Mike' instead of 'Atomic Victory.' But even so, all his official documents must have had his name listed as 'Atomic Victory Trotter'.

Wilmington Morning News - Nov 17, 1945

Louisville Courier-Journal - Aug 14, 1953

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 06, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Odd Names, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1940s

Atomic Brandy

1971: Soviet scientists claimed to have invented a method of making brandy in 10-15 days, as opposed to the 2-3 years it usually takes. Specifically, their method involved infusing grape juice with "oak shavings irradiated with 200 rads," and in this way rapidly transforming the juice into brandy.

San Rafael Daily Independent Journal - Sep 14, 1971

Some googling reveals that food scientists have continued to experiment with using ionizing radiation to speed up the aging process for alcoholic beverages. For instance, here's a 1999 article about Brazilian scientists using radiation to speed up the aging of cachaca.

Would the resulting brandy or cachaca be radioactive? Apparently no more so than any alcoholic drink.

Consider this Snopes article: Does U.S. Law Require Alcohol to Be Radioactive?

The answer is that, no, the law doesn't require alcohol to be radioactive, but any alcohol made from plants is going to be slightly radioactive because the plants have been exposed to cosmic rays. As opposed to synthetic alcohol made from petroleum, which will be far less radioactive. So, one way to determine if alcohol came from plants or petroleum is to measure how radioactive it is. Most people, I assume, would prefer the more radioactive stuff.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 11, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Inebriation and Intoxicants, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters

The best defense against an atomic bomb…

"... is not to be there when it goes off."Advice which remains true to this day.

Manchester Evening News - Feb 18, 1949

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jun 18, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: War, Weapons, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1940s

“Goodbye, Three Mile Island”

With Chernobyl in the news again, perhaps we need to revive this song.Gary and the Outriders, a local music group, recorded an original song, "Goodbye T.M.I. (The Ballad of Three Mile Island)," and released it as a 45 rpm record. Its catchy melody contrasts with its dire refrain: "Goodbye, goodbye to your life, T.M.I."

Posted By: Paul - Tue Apr 19, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Music, Regionalism, Riots, Protests and Civil Disobedience, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1970s

Recipes for the fallout shelter housewife

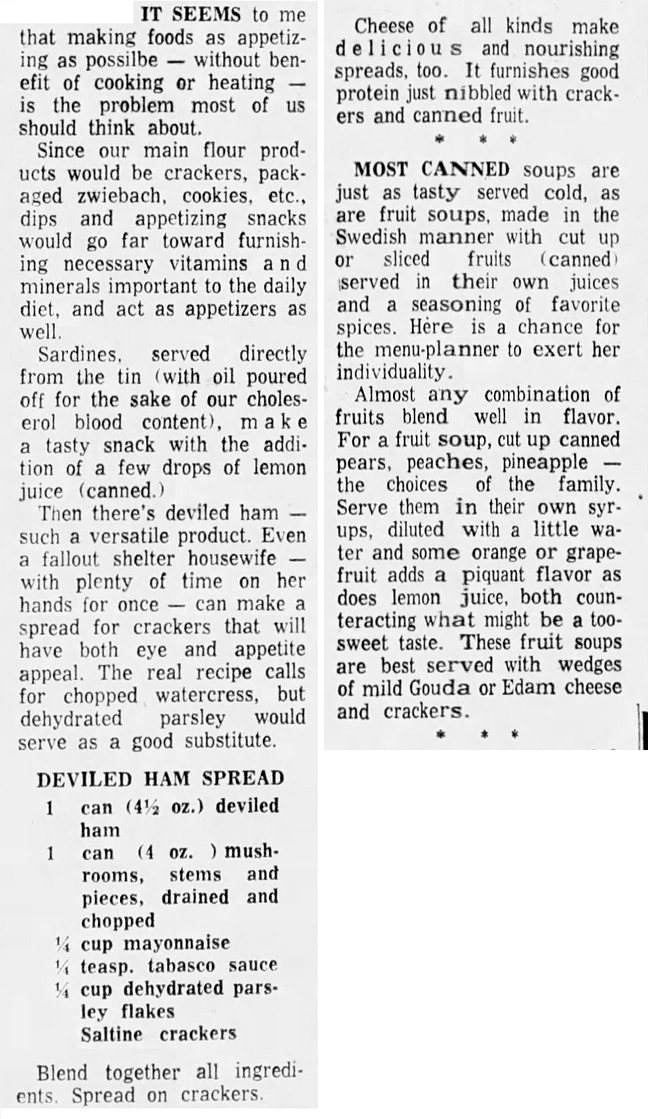

Marie Adams, food editor of the Charlotte News, felt that nuclear war shouldn't stop a "fallout shelter housewife" from providing her family with tasty meals and "appetizing snacks". In a 1961 column (Sep 7, 1961) she offered suggestions for fallout shelter meals that included deviled ham and parsley dip served with tomato juice, swedish fruit soup with cheeses, and vichyssoise with crackers.

A response from a reader of the Charlotte News:

Charlotte News - Sep 11, 1961

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 22, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Food, War, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s

Nuclear Tunneling

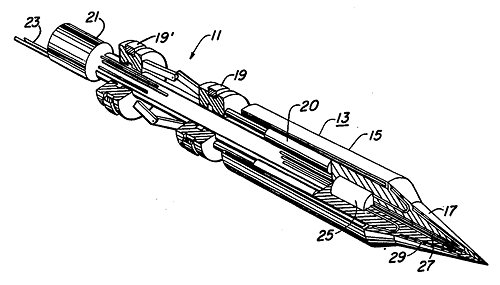

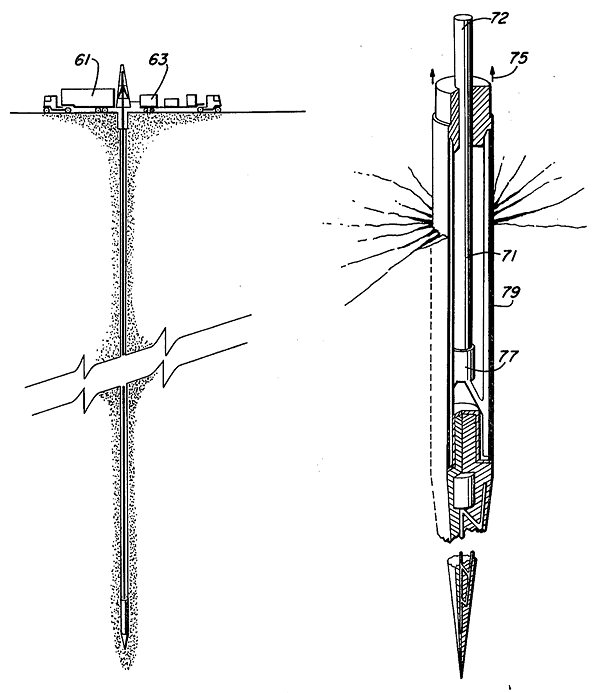

One of the projects that researchers at Los Alamos have worked on is a 'subterrene'. This is a nuclear-powered tunneling machine capable of boring through solid rock at high speed by melting the rock. They were granted a patent (No. 3,693,731) for this in 1972.

There's some info about this (as well as it's possible use on the Moon or Mars) in the book Terraforming Mars:

The same technology was proposed by Joseph Neudecker and co-workers, in 1986, as a means by which tunnels might be bored upon the Moon in order to construct a subsurface transportation system. Describing their nuclear-powered melting machine as a SUBSELENE, Neudecker et al. calculate that a fission-reactor-heated, 5-m diameter tunneler could be made to advance by as much as a 50-m per day through the lunar subsurface. This tunneling, they argued could (indeed, must) be operated remotely. Importantly, for tunnel coherence and stability, the material melted at the front of the SUBSELENE would be extruded at its backend to form a glass lining on the tunnel wall.

Wikipedia has an article about the Subterrene, noting the rumor that the Soviets actually built such a device which they called the "battle mole".

Posted By: Alex - Sat Feb 19, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Caves, Caverns, Tunnels and Other Subterranean Venues, Patents, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1970s

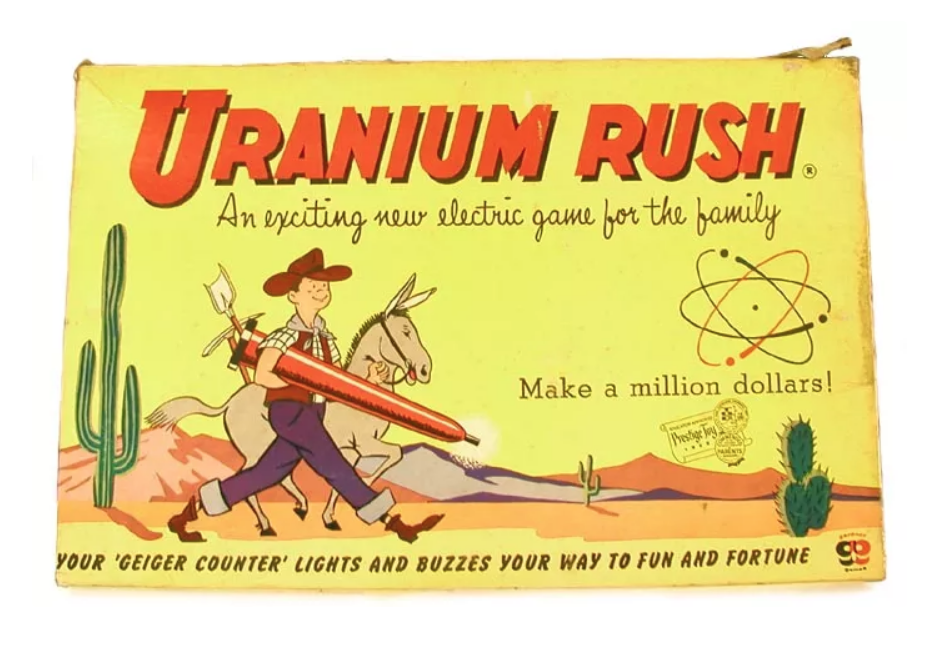

Uranium Rush Board Game

More pics and info at Board Game Geek.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Dec 07, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Games, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1950s

Atomic Chess

Atomic Chess is a variant of chess that was invented by Nasouhi Bey Tahir, the Transjordanian Deputy Minister of Agriculture, in 1949. Most of its rules were the same as the traditional game except that it was played on a larger board (of 144 squares) and when a pawn was promoted it would become an 'atomic bomb'. When used it would annihilate all pieces (of both players) within a radius of six squares from the object of attack.The game also involved two other pieces, a tank and airplane, but I'm not sure how these were used.

Sydney Morning Herald - May 1, 1949

Chess.com describes a different version of Atomic Chess, that it says was introduced in 2000. This newer variant is played on a standard board, with the twist that "whenever a piece is captured, an 'explosion' reaching all the squares immediately surrounding the captured piece occurs. This explosion kills all of the pieces in its range except for pawns." Therefore, every capture, except by a pawn, is suicidal.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Oct 22, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Games, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1940s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |