Law

No makeup or men for five years

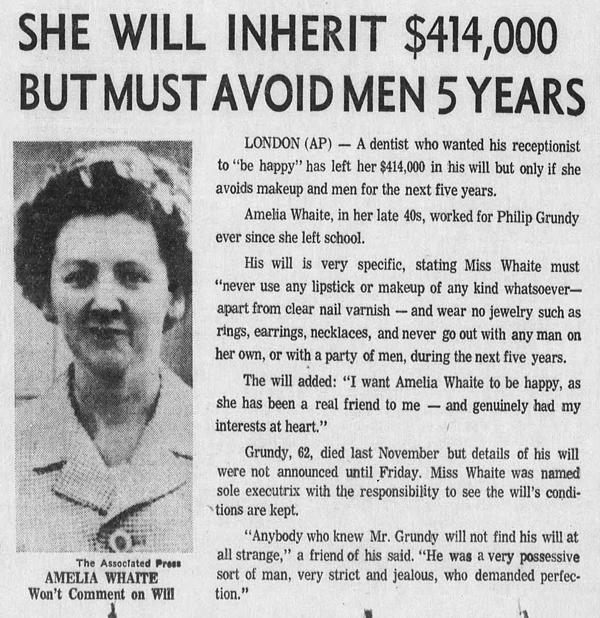

When British dentist Philip Grundy died in 1974, he left the bulk of his estate, slightly over $400,000, to Amelia Whaite, the receptionist at his practice. But with some unusual conditions. He forbid her from wearing lipstick or makeup, or going out with any men, for five years.$400,000 in 1974, adjusted for inflation, would be over $2,000,000 today. So a nice chunk of money.

However, Grunday also made Whaite the sole executor of his estate "with the responsibility to see the will's conditions are kept." So if she didn't follow the conditions was she supposed to self-report herself?

Atlanta Constitution - Mar 17, 1974

I found a forum where residents of Leyland, Lancashire (where Grundy worked) recalled going to his practice. Seems that, in addition to the money, he left behind a lot of traumatized patients. Some typical comments:

Some more info about Grundy and Whaite from a 1974 Associated Press article:

Four years later, Grundy was accused of addiction to inhaling anesthetic gas and was forbidden to practice for five years.

He resumed his practice in 1971 and built it into a flourishing enterprise with a staff of 14. . .

Miss Whaite now runs the practice, still with a 14-member staff.

Grundy sounds like he was a real piece of work.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 31, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Law, 1970s, Teeth

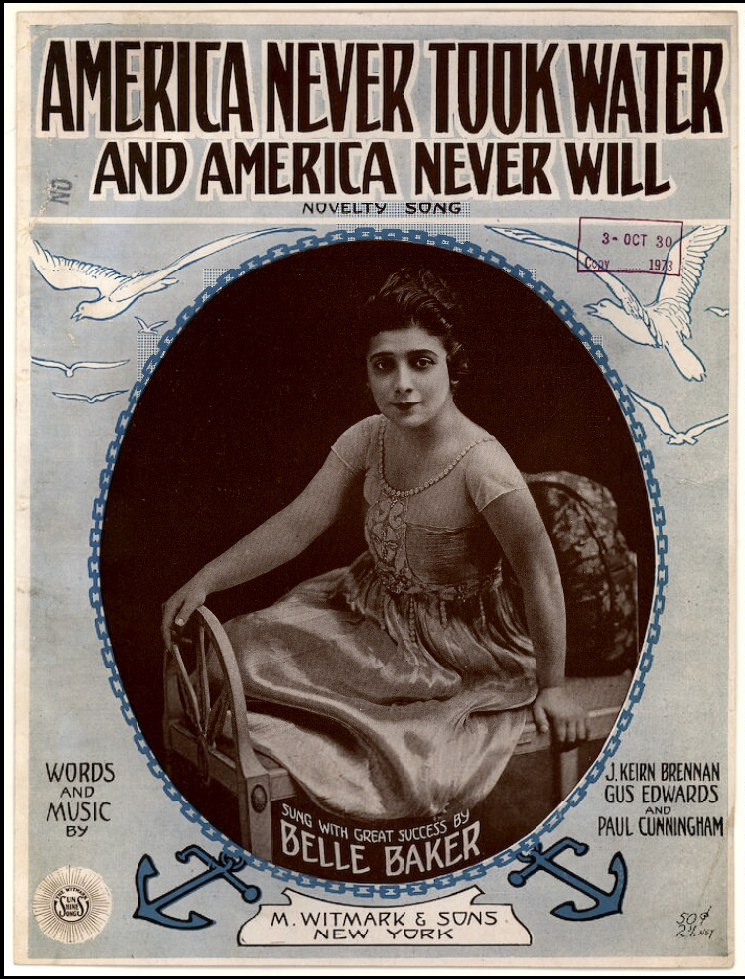

America Never Took Water

Sing along to this rousing anti-Prohibition ditty! Full lyrics here.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jul 23, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Government, Law, Music, Propaganda, Thought Control and Brainwashing, Alcohol

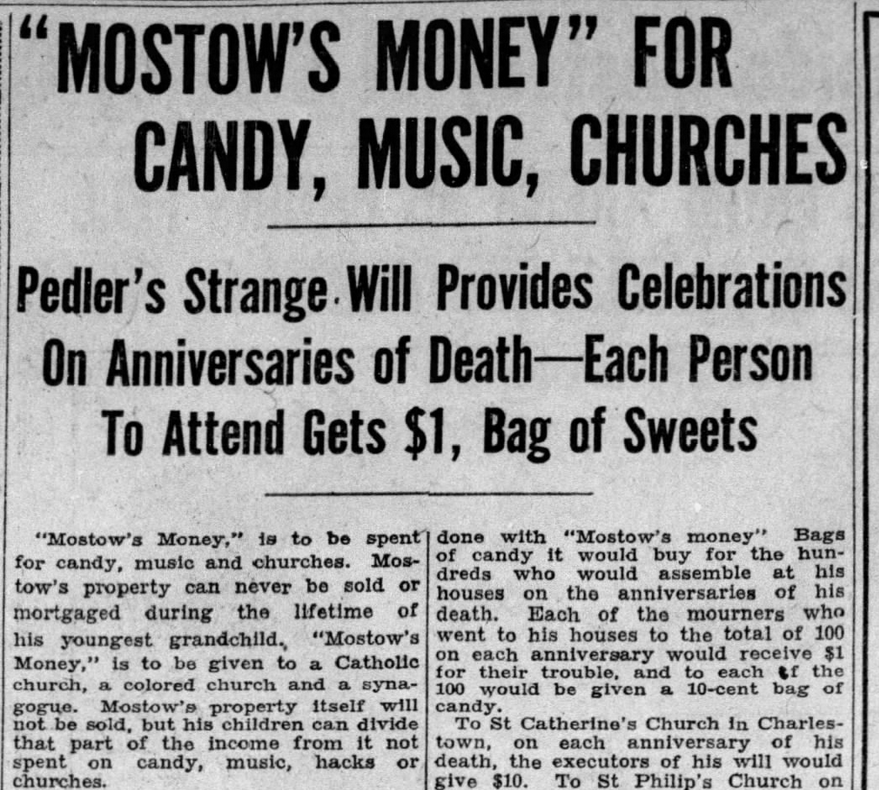

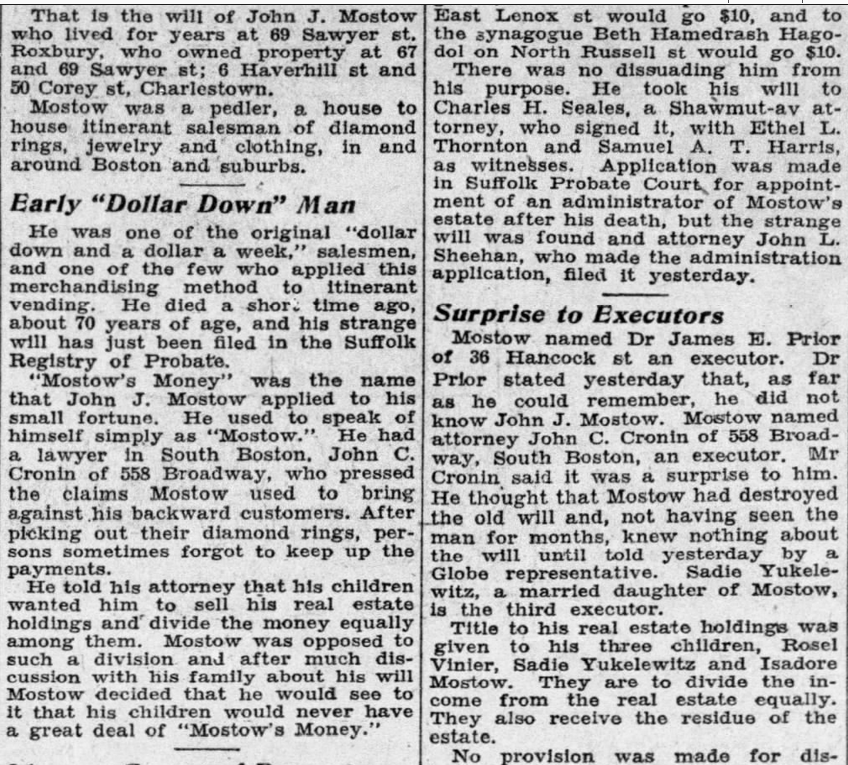

The Strange Will of John Mostow

Source: The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts)04 Apr 1928, Wed Page 16

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 06, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Death, Eccentrics, Law, Money, Candy, 1920s

Singing Jurors

Two different legal cases offer guidance on when singing jurors are considered grounds for a new trial, and when they're not. Details from the Virginia Law Register - April 1905.WHEN THEY'RE NOT:

From the case Collier v. State

WHEN THEY ARE:

From the case State v Demareste La

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 22, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Law, Music

Understanding the Law: The Worm

Understanding the Law: The Worm, Diane Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Posted By: Paul - Sun Feb 13, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Law, Lawsuits, PSA’s, Cartoons, 1990s

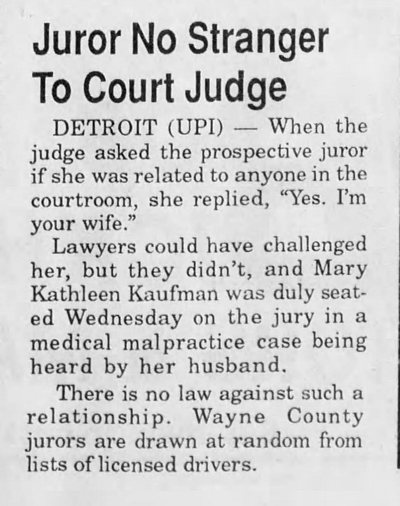

Judge’s wife serves as juror in his court

This was legal???

Macon Chronicle-Herald - Sep 8, 1989

Apparently so. Some googling reveals that this situation seems to happen fairly regularly.

Most recently, there was the case of Judge Thomas Ensor of Colorado whose wife served as a juror in his court. During the trial the judge repeatedly cracked jokes about the presence of his wife, such as, "Be nice to Juror 25. My dinner is on the line."

Inevitably the case was appealed, but in June 2020 the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that it was legal for Ensor's wife to be on the jury, noting that the defense lawyer could have objected to her sitting as a juror, but didn't. (Though the defense lawyer had said that he was afraid to challenge her.)

More info: ABA Journal

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 25, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Law, Judges

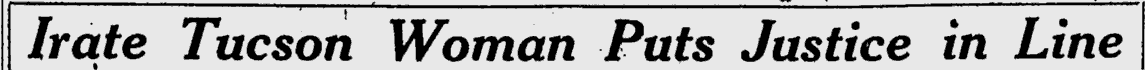

The 1000-Mile Courtroom

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jan 25, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Eccentrics, Law, Money, Outrageous Excess, Police and Other Law Enforcement, 1950s, Cars

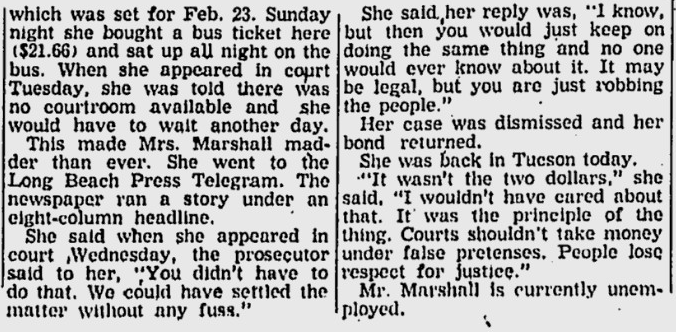

Isaac Parker, the Hanging Judge

His Wikipedia page tells us:Parker became known as the "Hanging Judge" of the American Old West, because he sentenced numerous convicts to death.[1] In 21 years on the federal bench, Judge Parker tried 13,490 cases. In more than 8,500 of these cases, the defendant either pleaded guilty or was convicted at trial.[2] Parker sentenced 160 people to death; 79 were executed.

Read a memoir that appeared two years after his death at this link.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Sep 17, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, History, Wild West and US Frontier, Law, Books, Nineteenth Century

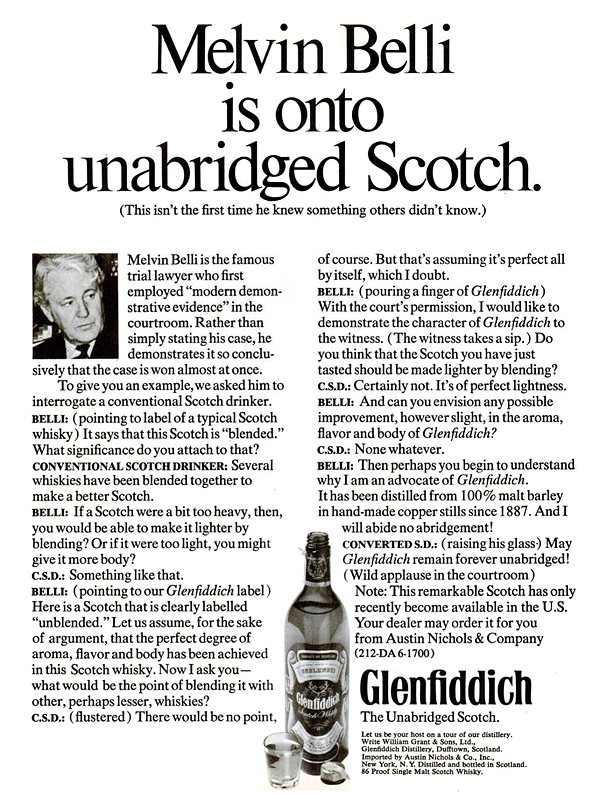

Melvin Belli Drinks Glenfiddich

The ad below, in which trial lawyer Melvin Belli endorsed Glenfiddich scotch, ran in the New York Times and New York Magazine in early 1970. Taken at face value, it doesn't seem like a particularly noteworthy ad. However, it occupies a curious place in legal history.Before the 1970s, it was illegal for lawyers to advertise their services. So when Belli appeared in this ad, the California State Bar decided he had run afoul of this law — even though he hadn't directly advertised his services. It suspended his license for a year. The California Supreme Court later lowered this to a 30-day suspension — but it didn't dismiss the punishment entirely.

Some high-placed judges felt sympathetic to Belli, which added fuel to the movement to end the 'no advertising' law for lawyers, and by 1977, the Supreme Court had struck down the ban on advertising, saying that it violated the First Amendment. That's why ads for legal services now appear all over the place. Compared to the ads one sees nowadays, Belli's scotch endorsement really seems like no big deal at all.

More info: Belli v. State Bar, "Remember when lawyers couldn't advertise?"

New York Magazine - Mar 2, 1970

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 16, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Law, Advertising, 1970s

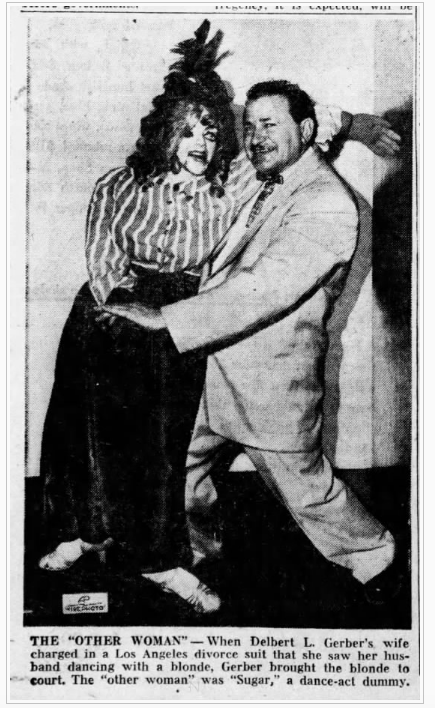

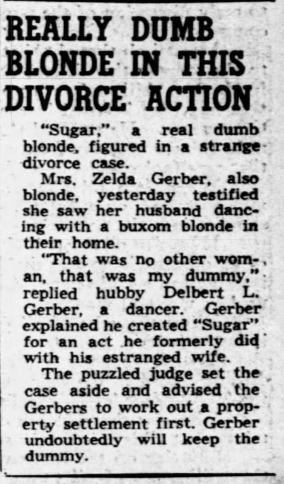

Dummy Divorce

Photo source: The Baltimore Sun Baltimore, Maryland 21 Aug 1953, Fri • Page 4

Text source: Los Angeles Evening Citizen News (Hollywood, California) 21 Aug 1953, Fri Page 11

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jun 19, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Law, Puppets and Automatons, Husbands, Wives, Divorce

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |