Psychology

Sympathetic Vomiting

An outbreak of mass vomiting at a school in North Carolina is being attributed to some kids getting upset stomachs from eating a combination of fruit juice and spicy chips, and then a bunch of other kids being triggered into “sympathetic vomiting.” That's when people vomit in response to seeing other people vomit. According to wisegeek.com, biologists suspect that the phenomenon has its roots in our evolutionary history:Other cases of sympathetic vomiting occasionally make headlines, such as in 2014 when a flight was forced to make an emergency landing after one person's vomiting caused five other people to do likewise.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 29, 2019 -

Comments (4)

Category: Psychology, Body Fluids, Stomach

The Lemon-Juice Bandits

In January 1995, Macarthur Wheeler and Clifton Johnson robbed a bank in Swissvale, Pennsylvania. However, they had a plan to avoid detection: they rubbed lemon juice on their faces. Their reasoning was that lemon juice can be used to make invisible ink, so surely it would conceal their faces from surveillance cameras as well. They even tested this hypothesis by taking polaroid pictures of each other smeared with lemon juice, and it seemed to work.Unfortunately, they showed up just fine on the bank's cameras, and they were identified and arrested several months later when the footage of the robbery was broadcast on a local news show.

This odd crime has an interesting postscript. The psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger of Cornell University read about it, and it inspired them to start thinking about the problem of stupidity: this being that stupid people often don’t realize they’re stupid. In fact, they think they’re quite smart, which leads them to do incredibly dumb things. This phenomenon (of dumb people not being able to recognize the limits of their competence) is now known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect. In the journal article in which they introduced the concept, Dunning and Kruger cited the lemon-juice bandits as their inspiration.

Tyrone Daily Herald - Jan 8, 1996

Pittsburgh Post Gazette - Mar 21, 1996

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 26, 2019 -

Comments (4)

Category: Stupid Criminals, Psychology, 1990s

Hangovers Due to Guilty Conscience

In 1973, Professor Robert Gunn advanced this theory.

Twenty years later, he was still pursuing the idea, as you can see in the scientific paper at the link.

To reappraise a prior study of hangover signs and psychosocial factors among a sample of current drinkers, we excluded a subgroup termed Sobers, who report "never" being "tipsy, high or drunk." The non-sober current drinkers then formed the sample for this report (N = 1104). About 23% of this group reported no hangover signs regardless of their intake level or gender, and the rest showed no sex differences for any of 8 hangover signs reported. Using multiple regression, including ethanol, age and weight, it was found that psychosocial variables contributed independently in predicting to hangover for both men and women in this order: (1) guilt about drinking; (2) neuroticism; (3) angry or (4) depressed when high/drunk and (5) negative life events. For men only, ethanol intake was also significant; for women only, being younger and reporting first being high/drunk at a relatively earlier age were also predictors of the Hangover Sign Index (HSI). These multiple predictors accounted for 5-10 times more of the hangover variance than alcohol use alone: for men, R = 0.43, R2 = 19%; and for women, R = 0.46, R2 = 21%. The findings suggest that hangover signs are a function of age, sex, ethanol level and psychosocial factors.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Feb 10, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Science, Experiments, Psychology, 1970s, 1990s, Pain, Self-inflicted and Otherwise, Alcohol

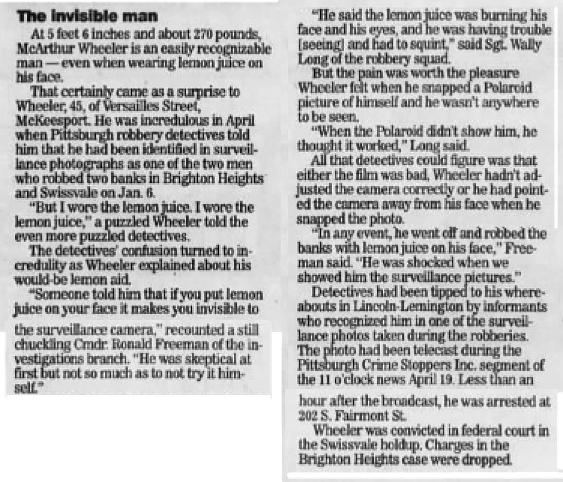

Hot Dogs vs Hamburgers

According to a study conducted by Dr. Leo Wollman (and reported in Omni magazine in 1980), one's preference for hot dogs or hamburgers when going out for a quick lunch has a deeper significance:"The people who eat hot dogs usually grab it and go," he said. "Hamburger eaters take more time. They're better dressed executive types, used to making decisions—well done, rare, ketchup or mustard."

I like both hot dogs and hamburgers, but if I was pressed for time I'd probably grab a hot dog over a hamburger. However, I don't match Wollman's hot-dog personality type at all. So I wouldn't put much stock in his results. And digging into his bio a bit further, it doesn't seem that he was exactly known for his credibility as a researcher.

Omni - July 1980

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 01, 2018 -

Comments (7)

Category: Food, Junk Food, Psychology

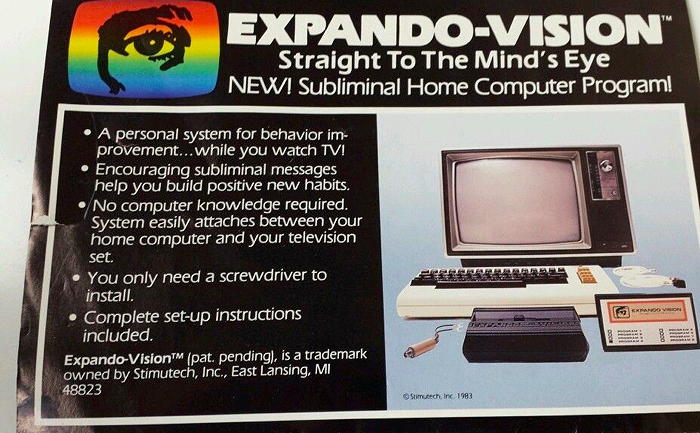

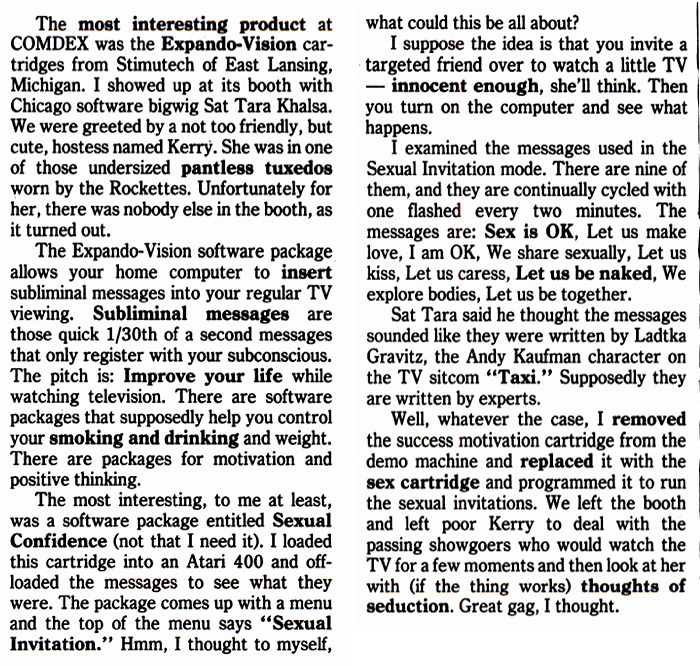

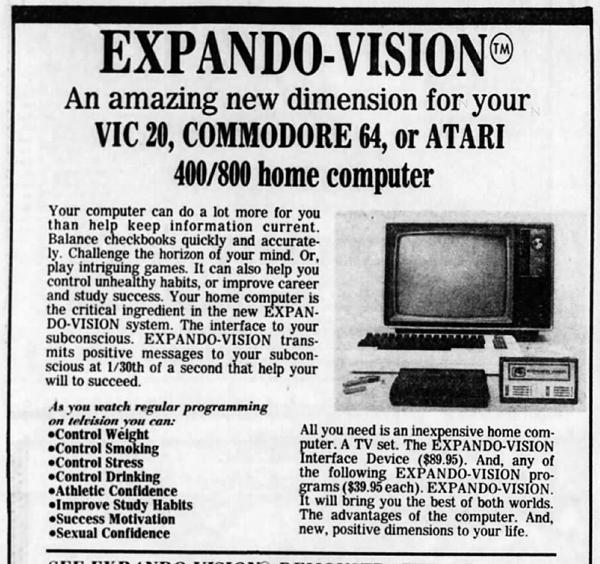

Expando-Vision

Introduced in 1983 by Stimutech. It was a device that could flash subliminal messages on your TV screen as you watched TV. The maker emphasized the ways this could be put to use for self-help (weight-loss, stop smoking, stop drinking, etc.). But they did sell a "Sexual Invitation" program that surreptitiously flashed messages of seduction: "Sex is OK, Let us make love, I am OK, We share sexually, Let us kiss, Let us caress, Let us be naked, We explore bodies, Let us be together.”

John Dvorak, InfoWorld - Dec 26, 1983

Lansing State Journal - Dec 4, 1983

Posted By: Alex - Fri Oct 19, 2018 -

Comments (2)

Category: Innuendo, Double Entendres, Symbolism, Nudge-Nudge-Wink-Wink and Subliminal Messages, Technology, Psychology, 1980s

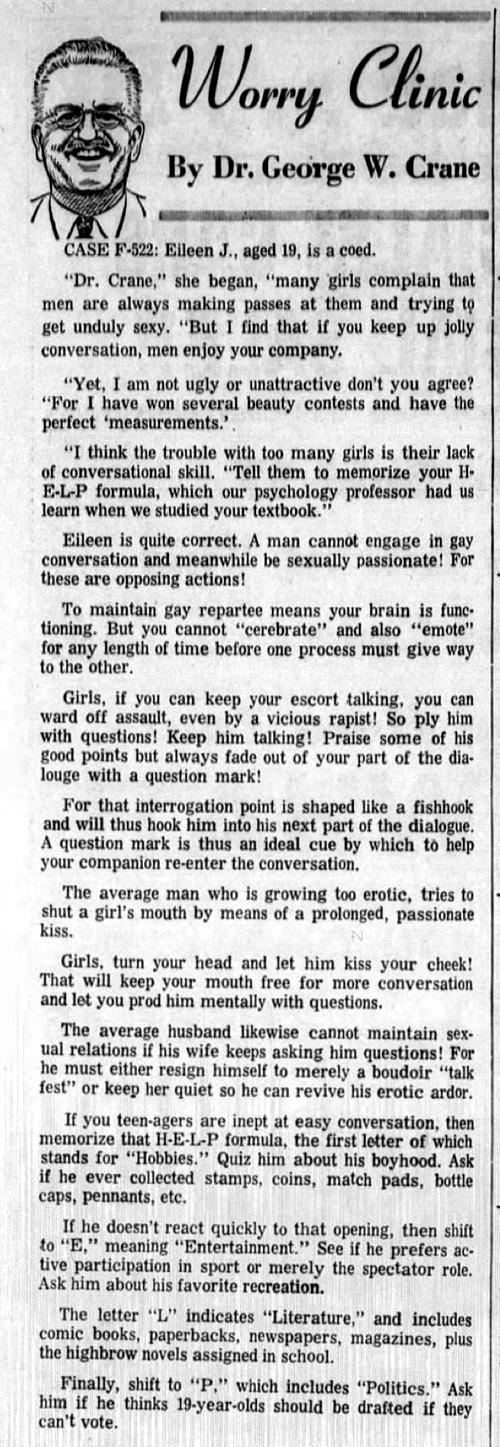

Dr. George W. Crane’s H-E-L-P Formula

A nugget of applied psychology wisdom from the 1960s: How young women could avoid date rape, according to Dr. George W. Crane, a well-known psychologist and newspaper columnist — "Girls, if you can keep your escort talking, you can ward off assault, even by a vicious rapist! So ply him with questions! Keep him talking! Praise some of his good points but always fade out of your part of the dialogue with a question mark!"Crane's logic was that, "A man cannot engage in gay conversation and meanwhile be sexually passionate! For these are opposing actions!" He offered the H-E-L-P formula as a mnemonic to help women keep the 'gay conversation' going. The idea was that they should quiz a potential assailant about Hobbies, Entertainment, Literature, and Politics, in that order.

There's more about Crane on Wikipedia. Apparently he developed the first computer dating organization. There's also this:

Mansfield News-Journal - Mar 21, 1968

Posted By: Alex - Wed Oct 17, 2018 -

Comments (8)

Category: Psychology, 1960s

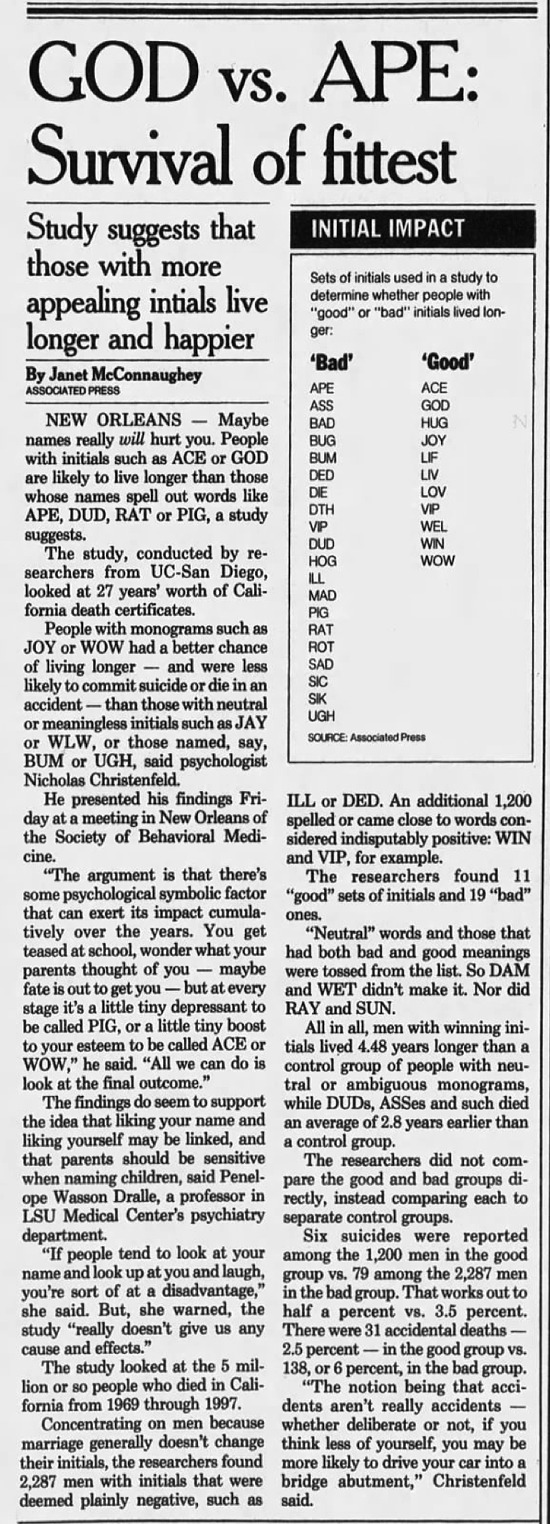

The Initials Effect

Found by psychologist Nicholas Christenfeld. The effect is that if the initials of your name spell out something positive (such as J.O.Y. or G.O.D.) you'll likely live longer than someone whose initials spell out something negative (B.A.D. or A.S.S.).From his article in the Journal of Psychomatic Research (Sep 1999):

San Francisco Examiner - Mar 28, 1998

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 05, 2018 -

Comments (4)

Category: Odd Names, Science, Psychology

Dentists smell fear

Recent research reveals that dentists can not only smell fear, but that when they do their job performance significantly declines. From New Scientist:Next, examiners graded the dental students as they carried out treatments on mannequins dressed in the donated T-shirts. The students scored significantly worse when the mannequins were wearing T-shirts from stressful contexts. Mistakes included being more likely to damage teeth next to the ones they were working on.

So, if your fear causes your dentist to start making more mistakes, I assume that will only increase your fear, causing your dentist to make even more mistakes, leading to a downward-spiraling cycle of terror.

The academic study is here.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 05, 2018 -

Comments (4)

Category: Experiments, Psychology, Teeth

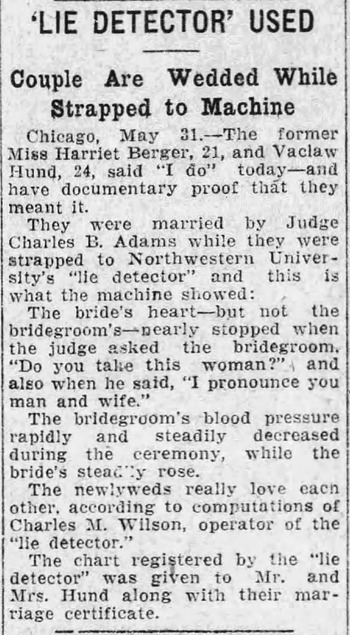

Wedding with lie detector

A lie detector used at the 1932 wedding of Harriet Berger and Vaclav Rund determined that their love was true.Vaclav and Harriet were still together in 1940, according to the census. So, score one for the lie detector. I haven't been able to trace their marriage any later than that. Though a V.R. Rund of the correct location and birth year died in 1989.

(Some media sources listed the bridegroom's name as Vaclaw Hund, but I think 'Rund' was his correct name, given the census data.)

Albuquerque Journal - June 14, 1932

Sioux Falls Argus-Leader - June 1, 1932

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jun 04, 2018 -

Comments (0)

Category: Psychology, 1930s, Weddings

Cheerleader Effect

image source: dwilliss/flickr

Pro-tip for non-photogenic people: You'll look better in a group photo than on your own. This is known as the Cheerleader Effect, and it's been scientifically verified. From medicalxpress.com:

Participants rated the attractiveness of faces presented in a group and individually. Regardless of gender, attractiveness ratings were higher when people were presented in a group compared to presented individually.

However, this does not mean the bigger the group—the more attractive you are. The authors found that group size, whether 4, 9, or 16 individuals, had no effect on attractiveness ratings. Basically, a handful of friends is all you need to take advantage of this effect.

Importantly, studies have shown the cheerleader effect to be reliable. Additional studies published in 2015 and one just this month continue to find a groups' attractiveness is significantly higher than the attractiveness of an individual group member.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Mar 04, 2018 -

Comments (2)

Category: Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Psychology

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |