The Lice-Infested Underwear Experiment

During World War II, millions of men served their country by fighting in the military. Hundreds of thousands of others worked in hospitals or factories. And thirty-two men did their part by wearing lice-infested underwear.

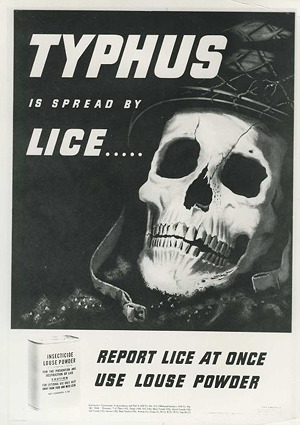

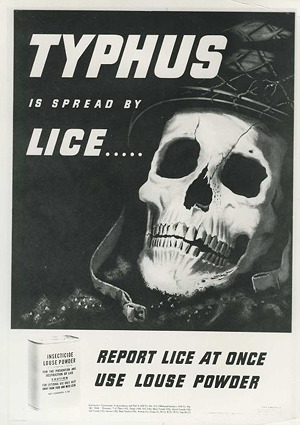

It began with the recognition of the serious public-health problem posed by body lice (Pediculus humanis corporis). Being infested by these tiny insects is not only unpleasant, but also potentially deadly, since they're carriers of typhus. During World War II, medical authorities feared that the spread of lice among civilian refugees could trigger a widespread typhus epidemic, leading to millions of deaths, as had happened in World War I.

It began with the recognition of the serious public-health problem posed by body lice (Pediculus humanis corporis). Being infested by these tiny insects is not only unpleasant, but also potentially deadly, since they're carriers of typhus. During World War II, medical authorities feared that the spread of lice among civilian refugees could trigger a widespread typhus epidemic, leading to millions of deaths, as had happened in World War I.

In an attempt to prevent this, the Rockefeller Foundation, in collaboration with the federal government, funded the creation in 1942 of a Louse Lab whose purpose was to study the biology of the louse and to find an effective means of preventing infestation. The Lab, located in New York City, was headed by Dr. William A. Davis, a public health researcher, and Charles M. Wheeler, an entomologist.

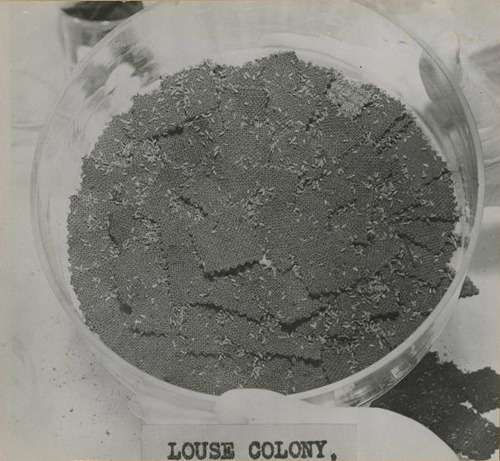

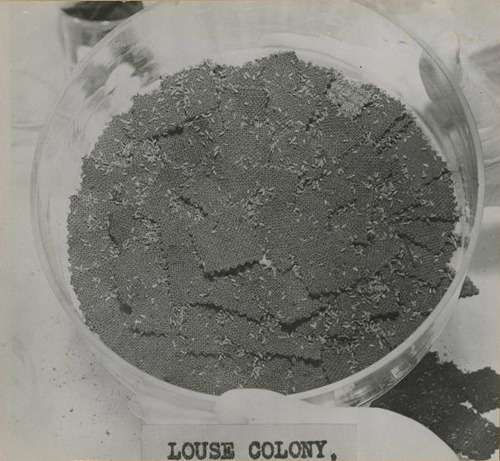

The first task for the Louse Lab was to obtain a supply of lice. They achieved this by collecting lice off a patient in the alcoholic ward of Bellevue Hospital. Then they kept the lice alive by allowing them to feed on the arms of medical students (who had volunteered for the job). In this way, the lab soon had a colony of thousands of lice. They determined that the lice were free of disease since the med students didn't get sick.

Next they had to find human hosts willing to serve as subjects in experiments involving infestation in real-world conditions. For this they initially turned to homeless people living in the surrounding city, whom they paid $7 each in return for agreeing first to be infected by lice and next to test experimental anti-louse powders. Unfortunately, the homeless people proved to be uncooperative subjects who often didn't follow the instructions given to them. Frustrated, Davis and Wheeler began to search for other, more reliable subjects.

In theory, the COs were always given a choice about whether or not to serve as guinea pigs. In practice, it wasn't that simple. Controversy lingers about how voluntary their choice really was since their options were rather limited: be a guinea pig for science, or do back-breaking manual labor. But for their part, the COs have reported that they were often eager to volunteer for experiments. Sensitive to accusations that they were cowardly and unpatriotic, serving as a test subject offered the young men a chance to do something that seemed more heroic than manual labor.

Eventually COs participated in a wide variety of experiments, but Davis and Wheeler were the very first researchers to use American COs as experimental subjects. And they planned to infest these volunteers with lice.

In July 1942, Davis and Wheeler took the train up to New Hampshire to meet their volunteers and begin the experiment. Davis took his lice with him. He kept them alive during the journey by allowing them to feed on his own blood.

Davis also took along other equipment for the experiment — pairs of blue cotton undershorts and light cotton sleeveless jerseys into which cloth patches had been sewn infested with lice and their eggs. These were the undergarments the men would be required to wear.

Upon arrival, Davis explained the rules of the experiment to the men. They would be required to wear the lice-infested undergarments for eighteen days without ever changing or removing them. They weren't allowed to purposefully kill the lice. Nor could they change their bedding. The only exception to these rules was that they were allowed to remove the undershirt if they got hot while working during the day. (Throughout the experiment the men continued working at their road construction duties.)

For the first nine days of the trial, the men simply wore the lice-infested undergarments. But during the second half of the trial, once they were fully crawling with bugs, they were divided into groups that were given various delousing powders to test. Again, Davis had specific instructions about how to apply the powders: "Spread it over your entire underwear and the armpits and crotch of outer clothing; pay particular attention to seams and folds. The better you spread it, the less they bite!"

Throughout the course of the trial, the researchers examined the men daily and counted the number of lice they found on them so that, after eighteen days, they had accurate information about the efficacy of each powder.

One of the volunteers later recalled what it was like wearing the lice-infested underwear:

Many of the men complained that the powders were more uncomfortable than the lice, because the powders had side-effects such as staining of the skin, nasal and anal irritation, and burning of the scrotum.

Despite these discomforts, the men obediently did as they were told — although a few of them later admitted to taking off their underwear at night because they felt excessively bothered by it. But even those that did this kept the underwear with them in the bed, and Davis decided that this minor infraction didn't effect the end results. In fact, he praised the cooperation of the men.

After tabulating all the results, Davis and Wheeler didn't find any powder that was entirely ideal as a delousing agent, although they did single out two they felt were the best of the bunch. But in an accident of historical timing, the efforts of all involved proved to be somewhat in vain, because soon after the conclusion of the experiment, the Department of Agriculture began testing a new powder, DDT, at its facility in Orlando, Florida. DDT proved far superior to anything that had been used before. In fact, it seemed like a miracle pesticide to researchers. It killed lice through nerve poisoning, but it didn't seem harmful to humans.

It was the use of DDT that prevented a typhus epidemic after World War II. As a result, the thirty-two volunteers couldn't claim to have contributed directly to this victory against the disease. But they nevertheless felt proud of their efforts. One volunteer drily remarked, "They also serve who only stand and scratch."

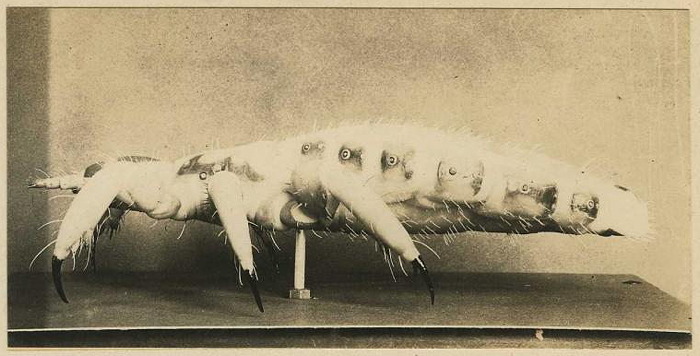

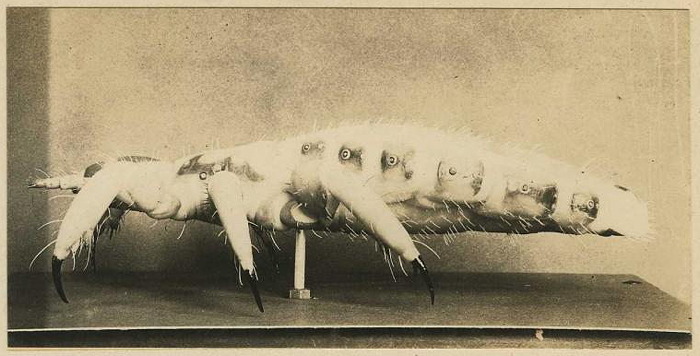

Model of a body louse, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Origin of the Experiment

World War II public health warning

Source: Nat. Museum of Health & Medicine

In an attempt to prevent this, the Rockefeller Foundation, in collaboration with the federal government, funded the creation in 1942 of a Louse Lab whose purpose was to study the biology of the louse and to find an effective means of preventing infestation. The Lab, located in New York City, was headed by Dr. William A. Davis, a public health researcher, and Charles M. Wheeler, an entomologist.

The first task for the Louse Lab was to obtain a supply of lice. They achieved this by collecting lice off a patient in the alcoholic ward of Bellevue Hospital. Then they kept the lice alive by allowing them to feed on the arms of medical students (who had volunteered for the job). In this way, the lab soon had a colony of thousands of lice. They determined that the lice were free of disease since the med students didn't get sick.

Next they had to find human hosts willing to serve as subjects in experiments involving infestation in real-world conditions. For this they initially turned to homeless people living in the surrounding city, whom they paid $7 each in return for agreeing first to be infected by lice and next to test experimental anti-louse powders. Unfortunately, the homeless people proved to be uncooperative subjects who often didn't follow the instructions given to them. Frustrated, Davis and Wheeler began to search for other, more reliable subjects.

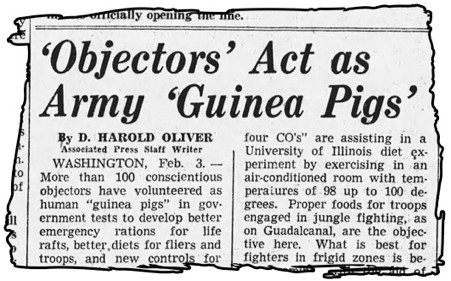

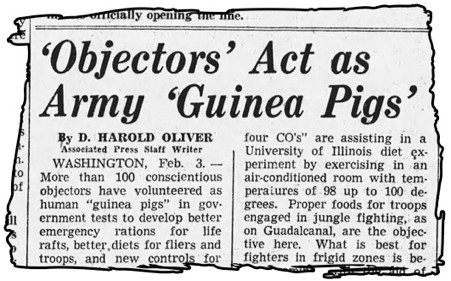

Conscientious Objectors

Eventually Davis and Wheeler hit upon conscientious objectors (COs) as potential guinea pigs. The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 allowed young men with religious objections to fighting to serve their country in alternative, nonviolent ways. At first they were put to work domestically at jobs such as building roads, harvesting timber, and fighting forest fires. But in 1942, inspired by the example of the British government, it occurred to U.S. officials that these young men were also a potential pool of experimental subjects for research, and they began to be made available to scientists for this purpose.

The Vancouver Sun - Feb 3, 1943

In theory, the COs were always given a choice about whether or not to serve as guinea pigs. In practice, it wasn't that simple. Controversy lingers about how voluntary their choice really was since their options were rather limited: be a guinea pig for science, or do back-breaking manual labor. But for their part, the COs have reported that they were often eager to volunteer for experiments. Sensitive to accusations that they were cowardly and unpatriotic, serving as a test subject offered the young men a chance to do something that seemed more heroic than manual labor.

Eventually COs participated in a wide variety of experiments, but Davis and Wheeler were the very first researchers to use American COs as experimental subjects. And they planned to infest these volunteers with lice.

Camp Liceum

Davis and Wheeler located a group of COs working at a camp in rural Campton, New Hampshire who seemed like ideal subjects. The setting they were in was isolated and allowed for greater experimental control, the men were willing to cooperate, and best of all, they didn't need to be paid. Arrangements were quickly made, and a side camp was established for the purpose of the experiment, forty miles from the base camp. The volunteers nicknamed their new home "Camp Liceum".In July 1942, Davis and Wheeler took the train up to New Hampshire to meet their volunteers and begin the experiment. Davis took his lice with him. He kept them alive during the journey by allowing them to feed on his own blood.

Davis also took along other equipment for the experiment — pairs of blue cotton undershorts and light cotton sleeveless jerseys into which cloth patches had been sewn infested with lice and their eggs. These were the undergarments the men would be required to wear.

Patches of fabric infested with lice

Upon arrival, Davis explained the rules of the experiment to the men. They would be required to wear the lice-infested undergarments for eighteen days without ever changing or removing them. They weren't allowed to purposefully kill the lice. Nor could they change their bedding. The only exception to these rules was that they were allowed to remove the undershirt if they got hot while working during the day. (Throughout the experiment the men continued working at their road construction duties.)

For the first nine days of the trial, the men simply wore the lice-infested undergarments. But during the second half of the trial, once they were fully crawling with bugs, they were divided into groups that were given various delousing powders to test. Again, Davis had specific instructions about how to apply the powders: "Spread it over your entire underwear and the armpits and crotch of outer clothing; pay particular attention to seams and folds. The better you spread it, the less they bite!"

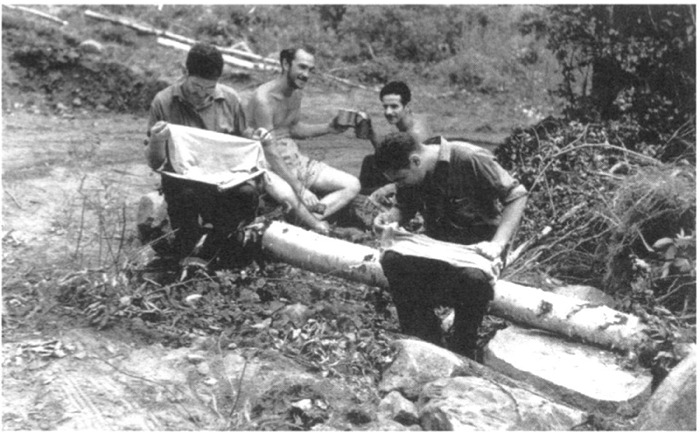

Throughout the course of the trial, the researchers examined the men daily and counted the number of lice they found on them so that, after eighteen days, they had accurate information about the efficacy of each powder.

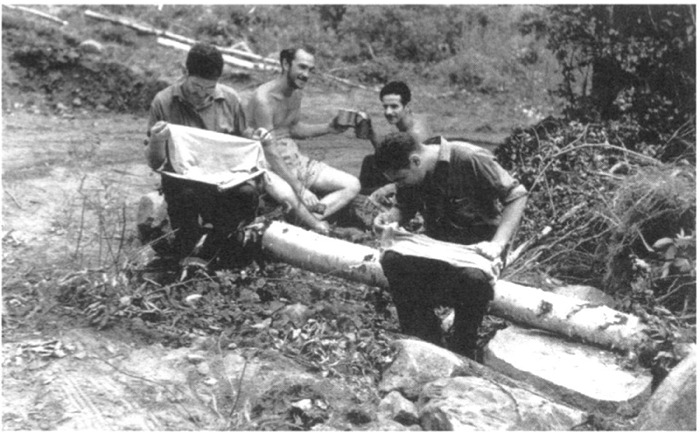

New Hampshire, 1942: Volunteers count the number of lice infesting the underwear of the experimental subjects. (Source: Rockefeller Archive Center)

Outcome

Between July and October 1942, Davis and Wheeler conducted three separate trials. During the third trial, as it grew colder, the volunteers were given lice-infested long underwear to wear instead of the cotton undershorts, but otherwise the protocol remained the same each time. Overall, they tested eighteen different delousing agents.One of the volunteers later recalled what it was like wearing the lice-infested underwear:

The first night was uncomfortable. The business of getting acquainted is often awkward, and possibly these laboratory-bred insects were just as embarrassed as were the campers. (It is hoped they slept better.) But, with few exceptions, there was no serious discomforture after that. The bites were no worse than those of the mosquito, and apart from a certain amount of uninhibited scratching in public, the men felt and behaved more or less normally.

Many of the men complained that the powders were more uncomfortable than the lice, because the powders had side-effects such as staining of the skin, nasal and anal irritation, and burning of the scrotum.

Despite these discomforts, the men obediently did as they were told — although a few of them later admitted to taking off their underwear at night because they felt excessively bothered by it. But even those that did this kept the underwear with them in the bed, and Davis decided that this minor infraction didn't effect the end results. In fact, he praised the cooperation of the men.

After tabulating all the results, Davis and Wheeler didn't find any powder that was entirely ideal as a delousing agent, although they did single out two they felt were the best of the bunch. But in an accident of historical timing, the efforts of all involved proved to be somewhat in vain, because soon after the conclusion of the experiment, the Department of Agriculture began testing a new powder, DDT, at its facility in Orlando, Florida. DDT proved far superior to anything that had been used before. In fact, it seemed like a miracle pesticide to researchers. It killed lice through nerve poisoning, but it didn't seem harmful to humans.

It was the use of DDT that prevented a typhus epidemic after World War II. As a result, the thirty-two volunteers couldn't claim to have contributed directly to this victory against the disease. But they nevertheless felt proud of their efforts. One volunteer drily remarked, "They also serve who only stand and scratch."

References

- Bateman-House, A. (July-August 2009), "Men of Peace and the Search for the Perfect Pesticide: Conscientious Objectors, the Rockefeller Foundation, and Typhus Control Research", Public Health Reports, 124: 594-602.

- Davis, W.A., & C.M. Wheeler (1944), "The Use of Insecticides on Men Artificially Infested With Body Lice", American Journal of Hygiene, 39(2): 163-76.

Comments

Truely, the Greatest Generation

Posted by crc on 09/04/19 at 12:16 PM

Since DDT has been discovered to be, in fact, harmful to humans, maybe this experiment will become useful again, as a template for other product testing.

Posted by Yudith on 09/05/19 at 06:09 AM

I got curious as to whether or not DDT is very harmful to humans so I checked around on...the internet...and found this link: https://www.acsh.org/news/2016/02/11/how-poisonous-is-ddt It is from the American Council on Science and Health. The article points out that the LD50 for DDT in larger mammals is the same as {"aspirin, caffeine and Tylenol (acetaminophen)" [copied and pasted from the above url]}.

I think article is a good read and the comments are interesting points of view.

I think article is a good read and the comments are interesting points of view.

Posted by Steve E. on 09/05/19 at 01:24 PM

I think, well actually I know, that the ACSH is a well known pro-chemical propaganda organization. DDT is more harmful in many different vectors than aspirin, caffeine, and Tylenol (whose own harms are no doubt real and minimized by other pro-corporate anti-truth organizations). The whole point of organizations are like that are to create materials to obfuscate and are spread by both willful and unwilling misinformation spreaders.

Posted by Floormaster Squeeze on 09/05/19 at 02:09 PM

Not all heroes wear capes. Some wear lice-infested underwear.

Posted by Brian on 09/12/19 at 09:09 PM

Commenting is not available in this channel entry.

Category: Health | Insects and Spiders | Experiments | Underwear | 1940s