The modern art movement rejected the traditional assumption that paintings should be as true-to-life as possible, or even that they should depict recognizable objects. One consequence of this rejection was that it often became unclear how to orient modern-art paintings when displaying them. Which way was up, and which way down? Confused exhibitors sometimes struggled to figure this out, and occasionally they got it wrong — much to the amusement of those members of the public who weren't convinced that modern art was actually real art.

The gallery below traces the history of this phenomenon of upside-down art — also taking note of accidentally sideways art.

17th-century scholar Athanasius Kircher, lampooned as a foolish expert

Tales of befuddled academics failing to recognize when objects were upside-down or reversed, and earnestly interpreting them anyway, had been circulating for a long time before the emergence of the modern art movement. These tales reflected skepticism about the judgement of intellectuals. The popular suspicion was that the bookish concerns of these scholars had made them too far removed from everyday common sense.

For instance, in his 1715 book

The Charlatanry of the Learned, Johann Burkhard Mencken related a story about the seventeenth-century scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was said that Kircher once received a piece of silk paper covered with strange characters. Believing it was Chinese script, he set to work to translate it. Only after many days of fruitless labor did he happen to see the paper in a mirror, at which point he realized that the cryptic characters were simply Roman letters printed in reverse. They spelled out a message authored by a prankster: "Do not seek vain things, or waste time on unprofitable trifles."

There's no good evidence this actually happened, but it shows that stories about the foolishness of experts were a well-established trope long before art exhibitors accidentally started hanging paintings upside down.

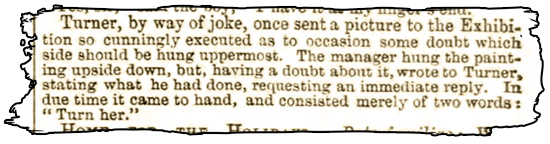

The Hampshire Advertiser - January 18, 1862

Art historians date the birth of the modern art movement to 1863, when Édouard Manet's convention-defying painting

"Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe" was rejected from the Paris Salon, prompting him to exhibit it elsewhere. However, by that year stories were already being told about experts confused by the orientation of paintings. Just the previous year, British newspapers had run an anecdote about

the painter J.M.W. Turner, claiming that he had once sent a work to a gallery, only to receive a query from the manager who suspected it had been hung upside down. Turner was said to have replied, "Turn her."

Like the story about Athanasius Kircher, it's doubful this actually happened. It was probably a joke inspired by the pun on Turner's name, combined with the fact that Turner's style in his later works had grown increasingly atmospheric (i.e. blurry). Some of his critics complained that the objects in his paintings were often barely recognizable. Nevertheless, Turner exerted a powerful influence on the subsequent modern art movement.

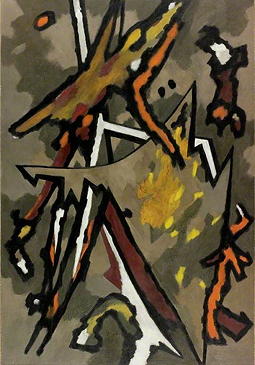

"Sunrise with Sea Monsters" (1845) by Turner.

An example of his increasingly abstract later work.

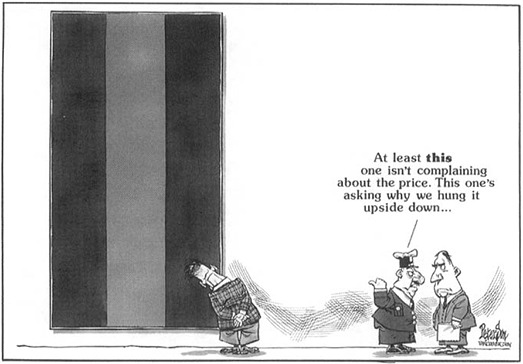

The West Plains Journal - July 6, 1911

As this 1911 cartoon demonstrates, by the early twentieth century the idea of modern-art paintings being accidentally hung upside down was already a well established joke, or urban legend. However, there weren’t yet any reports of this actually happening at any major exhibition — assuming the story about Turner was a mere anecdote. This would soon change.

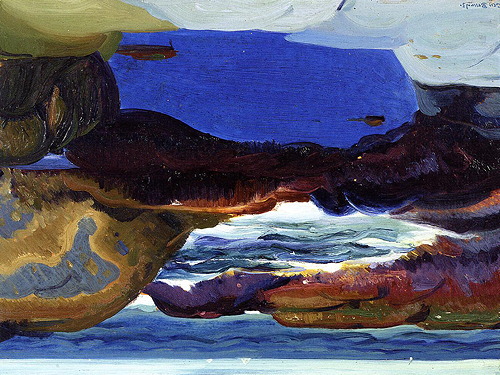

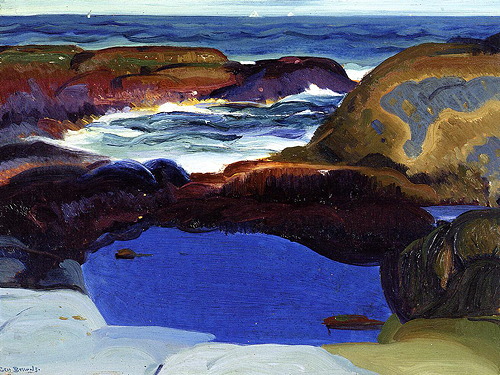

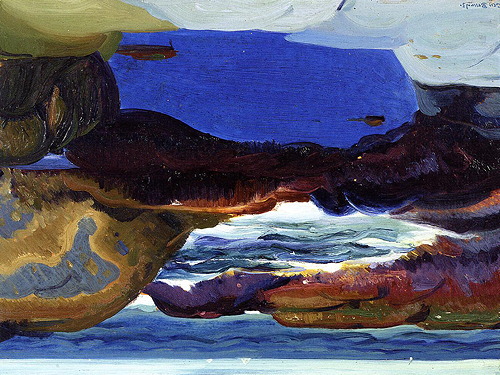

upside-down

right-side up

Finally, an actual, reported case of an upside-down painting. At a 1915 art exhibition in Grand Rapids, Michigan, "The Blue Pool," by George Bellows, was hung in a conspicuous location. Several artists gave talks at the event in which they referenced it, describing it as "modern in treatment." It was only after three weeks that the exhibitors realized they had hung the painting upside-down. When righted, the seemingly abstract swatches of color transformed into a more familiar scene of a pool of water surrounded by rocks.

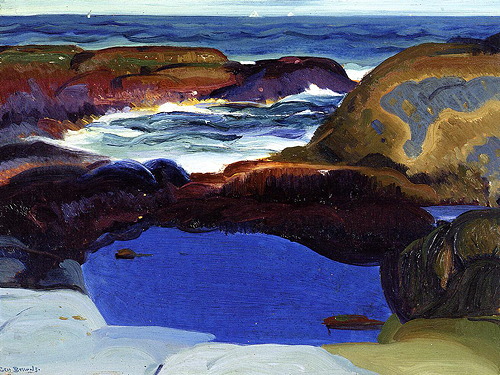

sideways

right-side up

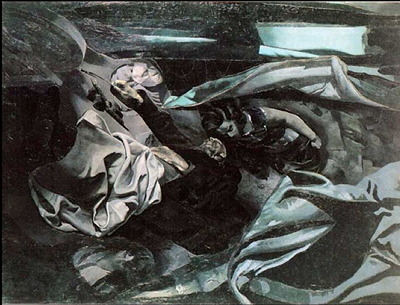

Edwin Dickinson completed his painting "The Fossil Hunters" between 1926 and 1928. It was then displayed at various locations including the Carnegie International Exhibition of 1928, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the New York Academy of Design. At the latter event, it won a prize of $500. It was only then, in 1929, that someone finally realized it had, all that time,

consistently been hung horizontally, whereas Dickinson had apparently intended it to be hung vertically. In other words, it was sideways. The fact that the painting had won an award while sideways made international headlines.

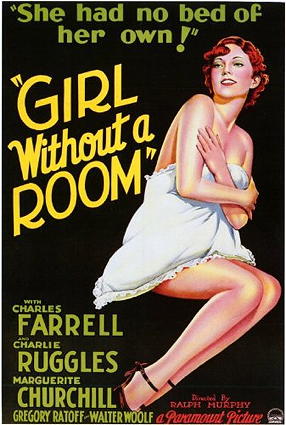

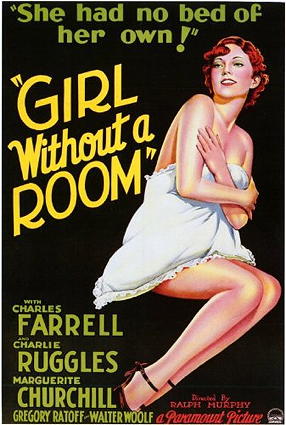

The 1933 Paramount movie “Girl Without a Room” told the fictional story of a young painter from Tennessee who won an art scholarship to Paris, got mixed up with Bohemians, abandoned his traditional style of art, and then ended up winning the top prize at a Paris show — even though his painting was hung upside down.

As wikipedia notes, "the film is notable as an example of Hollywood's attitude to abstract art in the 1930s."

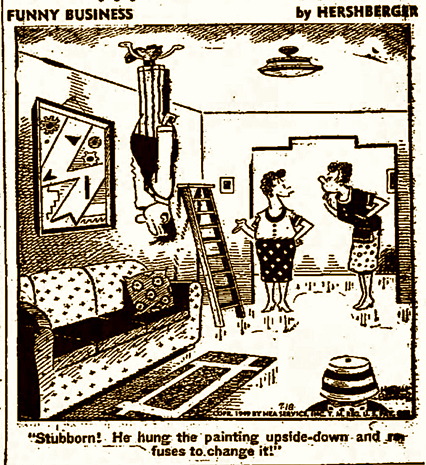

The Mexico Ledger (Mexico, Missouri) - July 18, 1949

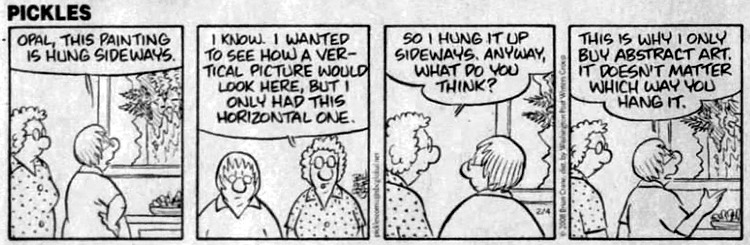

By the mid-twentieth century, jokes about upside-down abstract art had become a favorite of cartoonists.

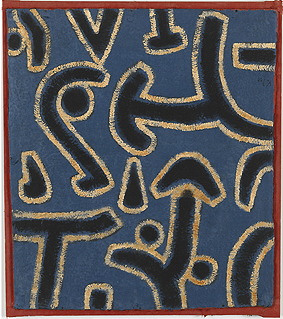

upside-down

right-side up

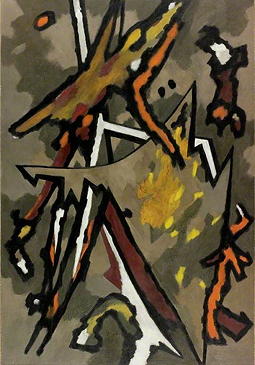

As part of the 1951 Festival of Britain, the Arts Council of Great Britain organized a show titled

60 Paintings for ’51. It included "Autumn Landscape" by William Gear. The selection of this painting for a £500 prize then provoked enormous controversy, due to its abstract nature. An article in the

Daily Mail described the work as “jam pot thrown on canvas.” Critics of the painting reacted with glee when, due to a printer’s error, it was subsequently reproduced upside-down in the Arts Council’s 1951 catalog. The April 1952 issue of

Picture Post magazine purposefully printed a picture of both of it and William Gear upside-down.

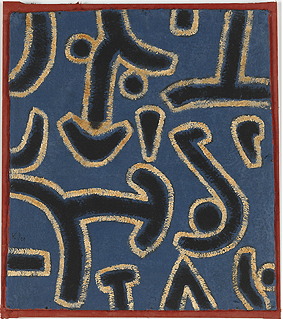

upside-down

right-side up

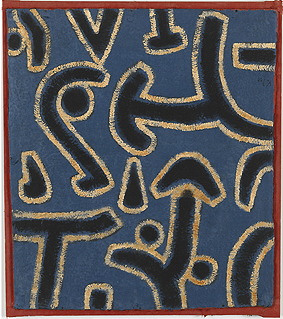

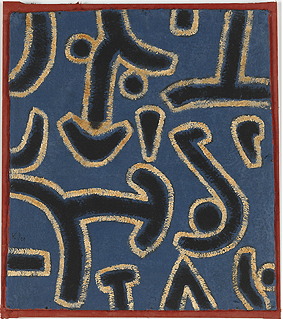

During a 1952 exhibition of modern art at the city museum in Amsterdam, two schoolboys noticed something odd about Paul Klee's 1938 painting "Ludus Martis." The artist's signature was upside-down and in the wrong corner. They pointed this out to the museum authorities, who then realized that the painting had been hung upside down.

In 1956, Anna P. Baker’s work “High Frequency Ping” won the top prize of $1500 at the Chicago Art Institute’s annual exhibition. But two students then noticed that Baker’s signature on the painting was upside down, prompting concerns that the work had been hung incorrectly. The exhibitors confessed they weren’t sure which was the right way around, but noted that they had asked contestants to label their paintings in the upper left hand corner on the back, and they had used this as a guide while hanging the works. Baker herself subsequently assured the Art Institute that they had oriented her painting correctly. “I signed it the second day,” she explained. “Then I painted on it for nearly a year and decided it looked better the other way around.”

sideways

right-side up

Sam Himmelfarb’s painting “Mosaic” won honors at a 1957 exhibition hosted by Chicago’s Art Institute. But when Himmelfarb visited the exhibition, he discovered that his painting had been hung sideways. The work depicted a group of people sitting outdoors on stone steps. Himmelfarb noted, “It was definitely a semi-abstract work, but not that abstract. I even painted faces on the people… The way they hung it, the people looked like they were falling off a cliff.” He also confessed that he hadn’t been sure whether to reveal the error because “maybe they wouldn’t think as highly of it if they knew it should be hung the other way.”

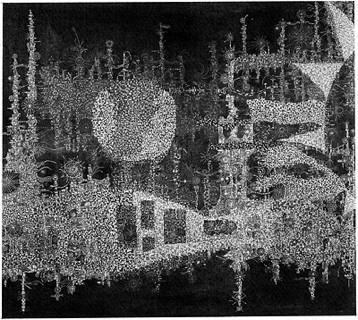

upside-down

right-side up

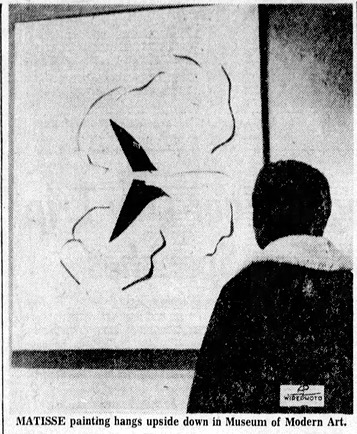

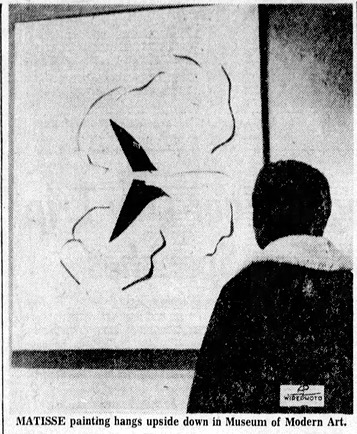

In 1961, New York's Museum of Modern Art hosted an exhibition of "The Last Works of Henri Matisse." Over one hundred thousand people attended the event during the first month, but only one person, the Wall Street broker Genevieve Habert, noticed that something looked wrong with the painting "La Bateau," which showed a sailboat and its reflection.

She returned several times to puzzle over the painting, until finally she tracked down a reproduction of it in a catalog. This led her to realize that the painting had been hung upside down. She pointed the mistake out to a guard who responded, “You don’t know what’s up and you don’t know what’s down, and neither do we.” Nevertheless, Mrs. Habert persisted, taking her concern to an employee at the information desk, who looked at the painting and agreed with her. Together, they brought the matter to the attention of the director of the exhibition, Monroe Wheeler. He promptly conceded the error, and had the painting righted. All in all, it had hung 47 days upside-down.

This incident was widely reported, and has since become the most famous example of a painting accidentally hung upside-down.

upside-down

right-side up

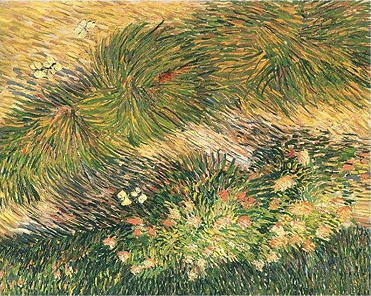

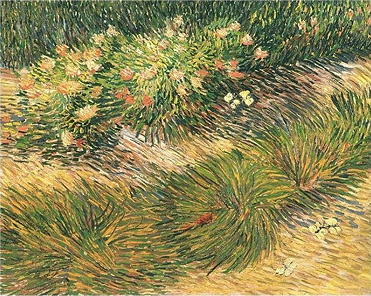

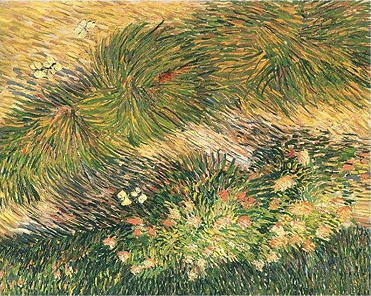

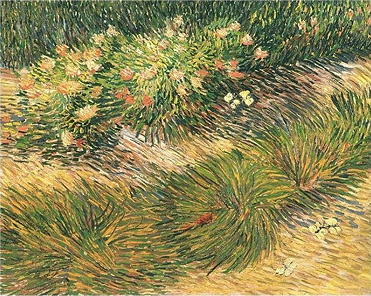

While visiting the National Art Gallery in London, 15-year-old schoolgirl Jean Cockburn noticed that Van Gogh's 1889 painting "Grass and Butterflies" was hung upside down. She pointed this out to an attendant who insisted it couldn't be so, but when she told other museum officials, they checked and realized she was right. The officials insisted, however, that it had only been hung that way for a mere 15 minutes. They explained that the painting had been taken away to be photographed, and the workmen who had rehung it weren’t familiar with Van Gogh’s works.

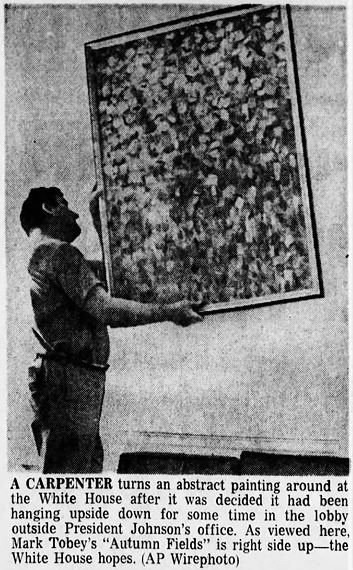

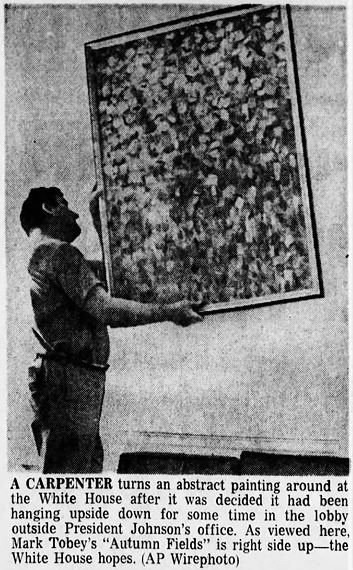

As a group of reporters waited in the lobby outside President Lyndon Johnson’s office in January 1968, they admired "Autumn Fields," a watercolor by American artist Mark Tobey that was on loan to the White House from the Smithsonian Institution. But when one newsman noticed that Tobey's signature was upside-down, debate ensued about whether the painting had been hung incorrectly. After a week, during which various members of the White House staff weighed in with their opinions, a consensus was finally reached: the painting was indeed upside down. The deciding factor was the observation that in every place where the watercolors had run, they were running uphill. A White House carpenter turned the painting around. The work had recently been exhibited in Japan where, apparently, it had also been hung upside down.

The Oil City Derrick - May 25, 1968

Grand Prairie Daily News - Oct 12, 1975

Horizontal

Vertical

Georgia O’Keefe completed her painting “Oriental Poppies” in 1928, and the University of Minnesota Art Museum acquired it in 1937. The painting was then displayed vertically at the museum for decades, until 1986, when Lyndel King, the museum's director, discovered that the original accession records for the painting indicated it was supposed to be hung horizontally. She indicated that, going forward, the painting's orientation would be corrected, but she also noted, "What the heck! It looks terrific either way!"

The traditional orientation

The corrected orientation

Georgia O’Keefe’s 1929 painting “The Lawrence Tree” depicts a tall tree that stood on author D.H. Lawrence’s ranch near Taos, New Mexico. For decades, this work was displayed with the trunk of the tree rising from the bottom right corner, but evidence emerged in 1989 indicating that this was upside-down. This evidence consisted of a photo showing the painting hung by O'Keefe herself, with the trunk descending from the top left corner, as well as a letter from her in which she complained that galleries were hanging the work upside down. The significance of the orientation was that O'Keefe had intended the painting to show how the tree might look to someone lying on the ground beneath it, gazing up at the stars.

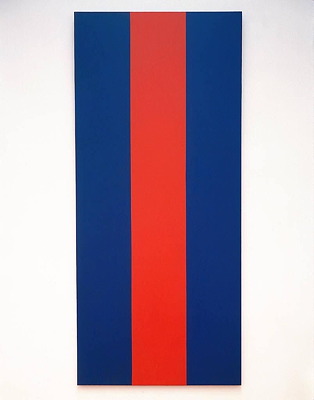

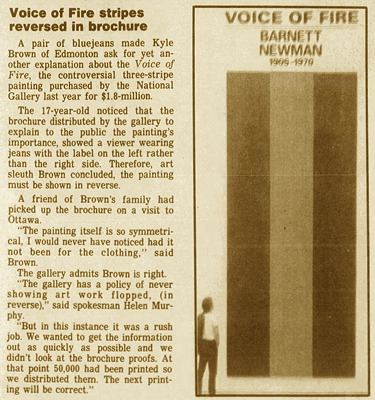

American artist Barnett Newman created “Voice of Fire” in 1967 as a special commission for the World’s Fair held that year in Montreal, Canada. But it was in 1989 that the work generated controversy, following its purchase for $1.8 million by the National Gallery of Canada. Many members of the public objected to the cost of the painting, its minimalist nature (a single, red stripe on a blue background), and the fact that Newman wasn’t Canadian.

The gallery released a brochure to explain why it had purchased the painting, but a young student, 17-year-old Kyle Brown of Edmonton, then pointed out that the image on the cover of the brochure, showing a man looking at "Voice of Fire," was reversed along the horizontal axis. He discovered this by noticing that the blue jeans on the viewer incorrectly had the label on the left side rather than the right. The gallery admitted the error. A spokeswoman said, “The gallery has a policy of never showing art work flopped, (in reverse). But in this instance it was a rush job. We wanted to get the information out as quickly as possible and we didn’t look at the brochure proofs.”

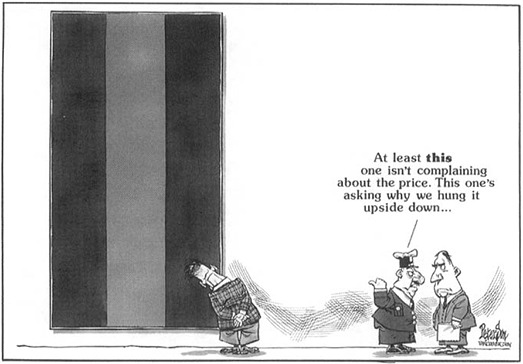

Wikipedia claims that further controversy ensued in 1992 following the discovery that the painting had been displayed upside-down ever since its acquisition. However, there's no evidence this was the case. The idea that it had once been hung upside down may have been inspired by several cartoons that ran in Canadian newspapers in 1990, such as the one below by Roy Peterson, that joked about this possibility.

Vertical Stripes

Horizontal Stripes

Controversy erupted in 2008 about two abstract works by Mark Rothko from his “Black on Maroon” series that were on display at the Tate Modern in London. The paintings, completed in 1958 and 1959, consisted of two stripes on a black background. They had been hung so that the stripes were vertical, but some critics argued that the location of Rothko’s signature on the back indicated that the stripes should be horizontal. Richard Dorment, art critic for the

Daily Telegraph, argued, “the lines create a sort of gate image when they are horizontal which can lead to a totally different interpretation when vertical because that really is the wrong way round.”

Defenders of the vertical orientation argued that when Rothko gifted them to the Tate Modern, back in 1969, the deed of gift had indicated that they were vertical paintings. Over the years, the paintings have, in fact, been displayed both ways, and the controversy about their correct orientation continues.

Lancaster Intelligencer Journal - Feb 4, 2008

Posted:

Nov 01, 2019