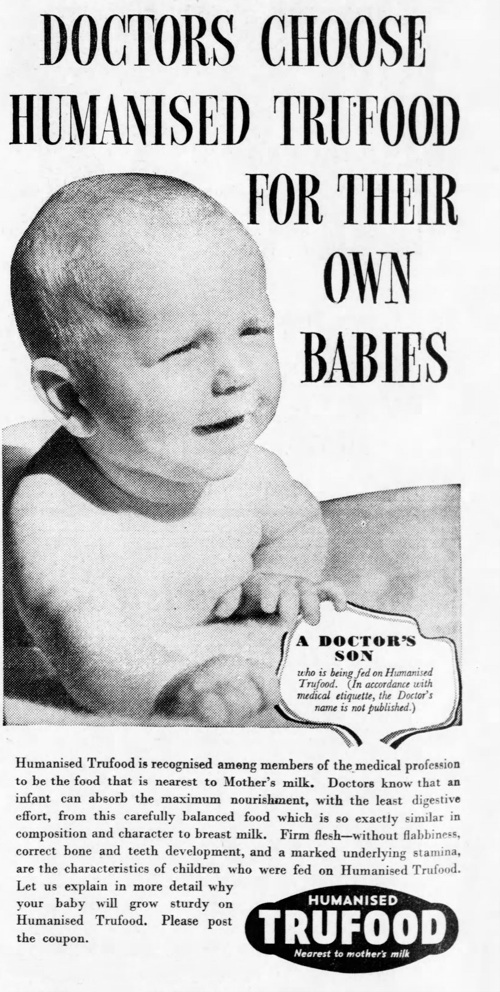

Babies

Humanised Trufood

Make sure your food has been humanised...

Daily Telegraph - Jan 28, 1937

Post-Graduate Medical Journal - June 1935

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 06, 2024 -

Comments (6)

Category: Babies, Food, Advertising, 1930s

Building houses with diapers

Concrete uses sand, and this is a problem due to a growing shortage of sand. However, Siswanti Zuraida, a researcher at the University of Kitakyushu in Japan, has proposed that cleaned and shredded diapers can be used in concrete as a sand replacement:More info: New Scientist

Posted By: Alex - Tue May 30, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Architecture, Babies, Excrement

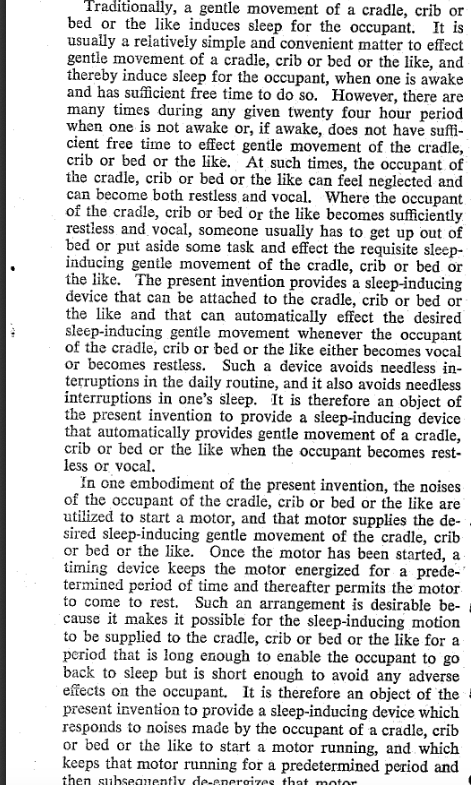

Wailing-Activated Rocking Cradle

Mister Muzzey had a good idea way back in 1962 and was actually ahead of his time--his patent also references a baby monitor to transmit the cries to the parents' room--but I wonder if his device ever went into production? As you can see below, there are modern versions today.

Amazon link.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Apr 03, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Babies, Domestic, Inventions, Patents, Parents, 1960s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

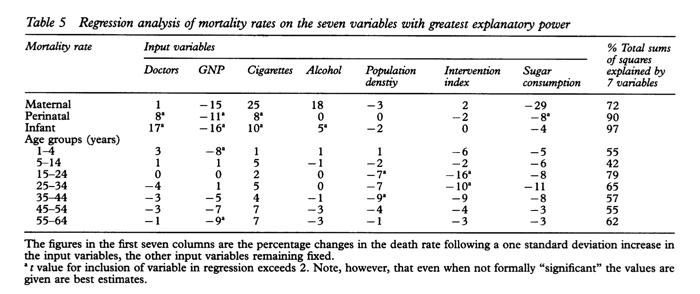

The Anomaly That Wouldn’t Go Away

In medical literature, the "anomaly that wouldn't go away" refers to a finding published in 1978 by a group of Welsh doctors (Cochrane, St Leger, and Moore). They had set out to examine the relationship between health services and mortality in the major developed countries, but in doing so they came across a correlation that surprised them — the more doctors there were per capita, the higher was the rate of infant mortality.The correlation wasn't a weak one. In fact, for infant mortality it was the strongest correlation in their study. The number of doctors per capita seemed to have a stronger negative impact on infant mortality than did the level of cigarette or alcohol consumption in the population.

Obviously the researchers found the correlation unsettling since, ideally, more doctors should result in fewer, not more, infants dying.

So why would more doctors correlate with higher infant mortality? The three doctors did their best to figure this out:

As the above passage indicates, they didn't think it was plausible that doctors themselves were somehow responsible for the elevated infant mortality, but nor could they come up with a satisfactory explanation for the correlation. So they called it "the anomaly that wouldn't go away."

I'm not sure if the correlation still holds true. I believe it still did about twenty years ago. Unfortunately much of the relevant literature is locked behind paywalls.

Over the years there have been quite a few attempts to explain the anomaly. I've listed two below. Again, I'm not sure if one has been accepted as THE explanation. So the anomaly may still persist.

It occurred to us that some of the countries richly endowed with physicians may obtain their large supplies by having bigger medical schools, larger classes, and thus less individual instruction of the medical student. The consequence could be a poorer standard of medical practice, the influence of which would be evident in the mortality of the younger age groups where the outcome of disease is most susceptible to the physician's skill.

The explanation proposed here is that, as compared with other regions, the expectation of opportunities in the growing industrial cities initially attracts an over supply of doctors. Once in practice, doctors in new regions enjoy fewer economies of scale, which means that they are more numerous as compared with the mature regions. These same industrialising cities attract rural immigrants whose health habits and supports break down in the context of city life. Thus, the places with the most doctors also have the highest death rates, but the two variables are associated only by common location.

More info (pdf): Cochrane, Leger, & Moore, "Health service 'input' and mortality 'output' in developed countries."

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 23, 2022 -

Comments (9)

Category: Babies, Death, Medicine

Skina Babe

Skina Babe, produced by Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., has been a popular brand of baby bath oil in Japan for decades. Mochida trademarked the name in the U.S. However, I don't believe it ever tried to introduce the product in an English-language market, which seems just as well.

Incidentally, Mochida also sells "Skina Fukifuki," which is a skin cleanser for senior citizens.

More info: mochida.co.jp

Posted By: Alex - Thu Dec 08, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Babies, Odd Names, Asia

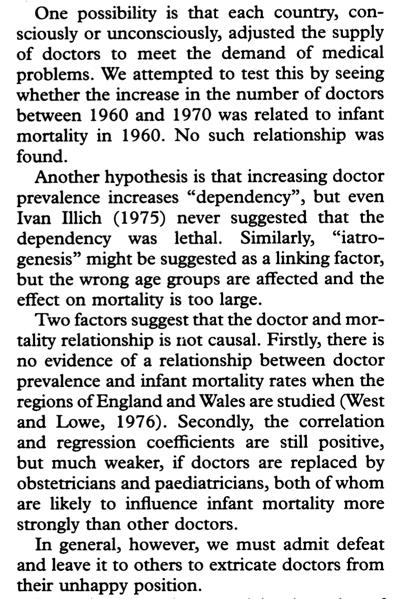

Would-Be Test-Tube Mothers of the 1930s

1939: Having filed for divorce from her husband, Mrs. Virginia Cleary announced that she was seeking a "perfect specimen of manhood" in order to father a "test tube" baby with her. Never mind that the technology for this didn't exist, and wouldn't for another four decades.She consulted with a doctor to determine what qualities the father of her "eugenic baby" would need to have:

- Between 28 and 32 years of age;

- Athletic in type, preferably light-haired;

- Unmarried, good habits, moderate in smoking and drinking;

- Strong, well-formed features;

- Strong personality, good ancestral background;

- Weight between 160 and 175 pounds.

San Francisco Examiner - Apr 26, 1939

Inspired by the example of Mrs. Cleary, Jean Gordon came forward and announced that she too wanted to mother a "test tube baby."

Des Moines Tribune - Apr 28, 1939

Posted By: Alex - Sun Sep 25, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Babies, 1930s

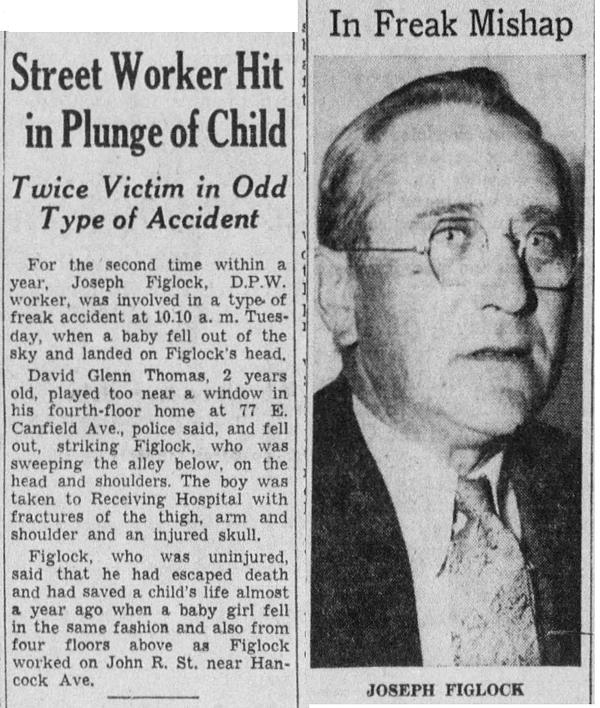

Watch out for falling babies

While Joseph Figlock was walking down the street, minding his own business, he twice had a baby fall from an overhead window onto his head. It first happened in 1937, and then again in 1938.Bad luck for him, but good luck for the kids who landed on him.

Detroit Free Press - Sep 28, 1938

Posted By: Alex - Sun Sep 04, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Babies, Synchronicity and Coincidence, 1930s

Lactation Cookies

'Lactation Cookies' are cookies that supposedly help to boost milk production in nursing mothers. Recipes vary, but the main ingredient seems to be oatmeal. So, they're essentially oatmeal cookies.I heard about them for the first time yesterday, but they've been around for a number of decades. The oldest reference to them I could find was in a 1974 zoo keepers journal discussing ways to increase milk production in orangutans. However, interest in them has spiked in the last decade, and there are now bakeries that specialize in making them, such as here and here.

Do lactation cookies actually work? The jury is still out on that question. Wikipedia, in its article on galactogogues (lactation inducers), notes that "Herbals and foods used as galactogogues have little or no scientific evidence of efficacy." But on the other hand, what harm can an oatmeal cookie do? And maybe they'd work via the placebo effect.

Incidentally, Guinness beer has also long been rumored to induce lactation and was often given to nursing mothers in Ireland.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 04, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: Babies, Food, Body Fluids, Pregnancy

Jazz Emotions

The Rock Island Argus - Feb 8, 1926

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 24, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Babies, Censorship, Bluenoses, Taboos, Prohibitions and Other Cultural No-No’s, Music, 1920s

Peat Moss Diapers

A manual on infant care, released by the U.S. Department of Labor in 1914, recommended peat moss (aka sphagnum moss) for use in diapers:Such a pad (i.e., a pad of sphagnum moss inclosed in cheesecloth) weighing only an ounce will completely absorb and retain a quarter of a pint of urine—say as much as would be passed in the night. This is infinitely cleaner and healthier than allowing the urine to spread over a wide area of napkin and nightdress, and thus cause extensive chillding and more or less irritation of the skin. Dry sphagnum forms an extremely light, clean, airy, elastic pad, which will yield in any direction and accommodate its shape to the parts.

Those living in the country where this moss grows may find it a great convenience to pick and dry the moss for this or other domestic purposes.

peat moss

Some googling reveals that Native American tribes, way back when, would often use peat moss for diapers.

And at the Earthling's Handbook you'll find an account by a modern-day couple who used peat moss for diapers and reported positive results:

Posted By: Alex - Sat Feb 26, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Babies, Nature

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |