Smells and Odors

Follies of the Madmen #563

Obviously whatever this gal was cooking smelled so hideous that she needed to conceal the odors.

Posted By: Paul - Mon May 01, 2023 -

Comments (5)

Category: Domestic, Food, Advertising, 1960s, Smells and Odors

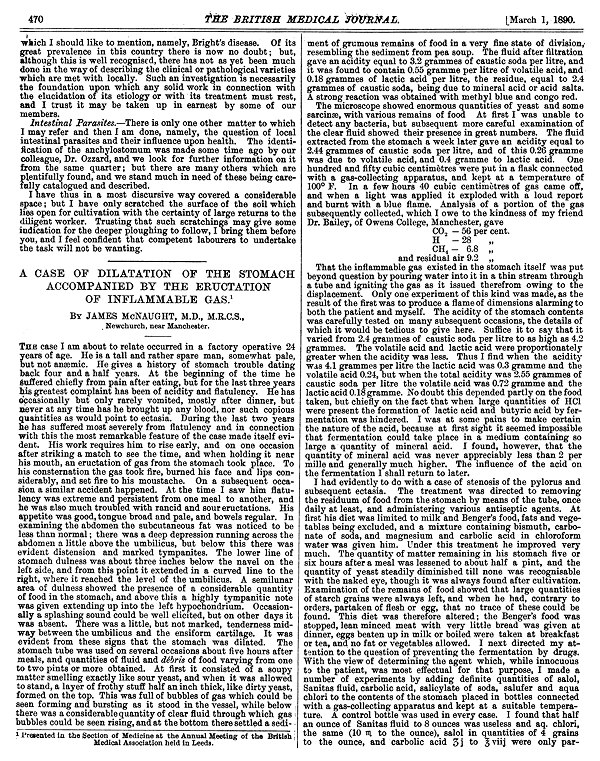

Burned by a belch

In 1890, Dr. James McNaught of Manchester reported in The British Medical Journal the strange case of a 24-year-old factory worker whose burp caught on fire while he was holding a match, badly burning his face and lips. McNaught managed to replicate the burning belch with the man in his office, confirming it really did happen. He diagnosed the problem as the "eructation of inflammable gas" from the man's stomach.McNaught concluded that the man suffered from a disorder that caused food to ferment in his stomach and produce flammable gas, instead of being digested. He advised the man to eat foods that would pass more quickly out of his stomach, to avoid the fermentation.

More info: British Medical Journal, "A Case of Dilatation of the Stomach Accompanied by the Eructation of Inflammable Gas"

Posted By: Alex - Fri Apr 21, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Health, Stomach, Smells and Odors

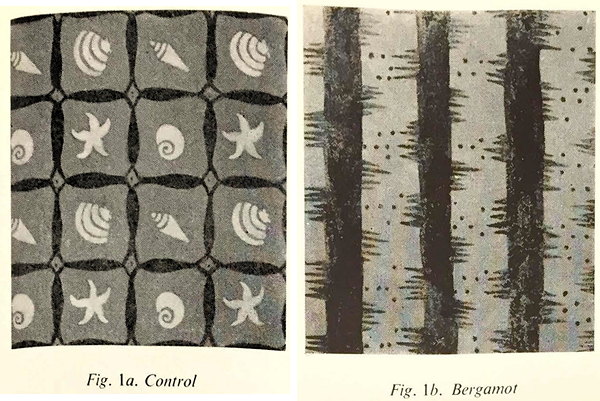

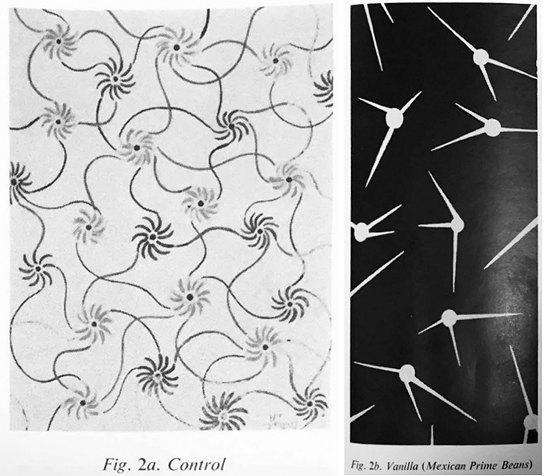

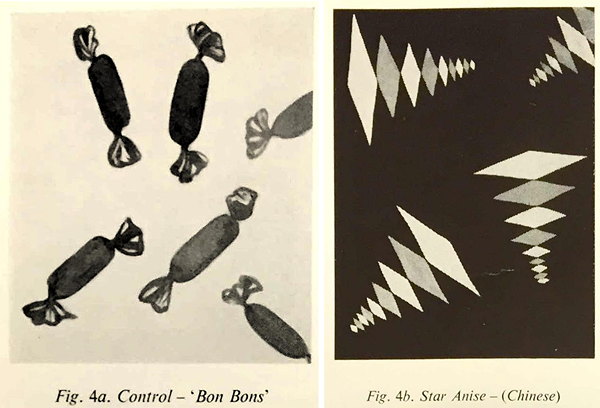

The influence of odors on creative thinking

There have been a variety of studies examining how psychoactive drugs affect behavior and creative output. But could smells also have a psychoactive effect? That was the question posed in a 1958 experiment conducted by scientist Leo H. Narodny — published in an obscure trade journal, The Perfumery & Essential Oil Record. Narodny wrote: "It may be possible, by inhaling certain odours, to influence creative imagination without endangering the whole brain by an excessive dosage of drugs."He used a textile designer as his test subject. Every day, for two weeks, he had her draw a design while breathing unscented air. Then, after breathing in air saturated with an odorous essential oil (such as bergamot, vanilla, peppermint, or cedarwood), she drew a second design. Some of the results are below.

It was hard to draw conclusions based on such a small sample size, but Narodny felt that the designer tended to draw more abstract patterns when exposed to the essential oils.

Nadia Berenstein offers more details about the experiment on her "Flavor Added" blog.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Mar 25, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Art, Experiments, Psychology, Smells and Odors

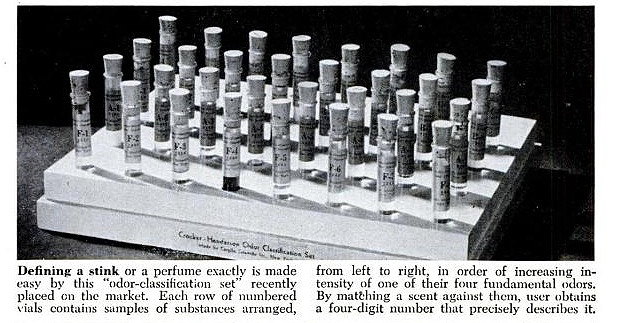

The Crocker-Henderson Odor Classification System

In the early twentieth century, odor researchers Ernest Crocker and Lloyd Henderson created a classification scheme that allowed them to number and catalog every smell in the world. Kind of like a Dewey decimal system for smells. Every different odor was assigned a four-digit code.Their system was based on the premise that every smell is a combination of four "primary odors." So the four-digit code was created by judging and listing the relative strength of each primary odor.

The problem was that judging the relative strength of each primary odor in any one smell turned out to be a very subjective process. Other people struggled to replicate the numbers that Crocker and Henderson came up with. So their system was never adopted by other researchers.

More info: NadiaBerenstein.com

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 15, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Science, Smells and Odors

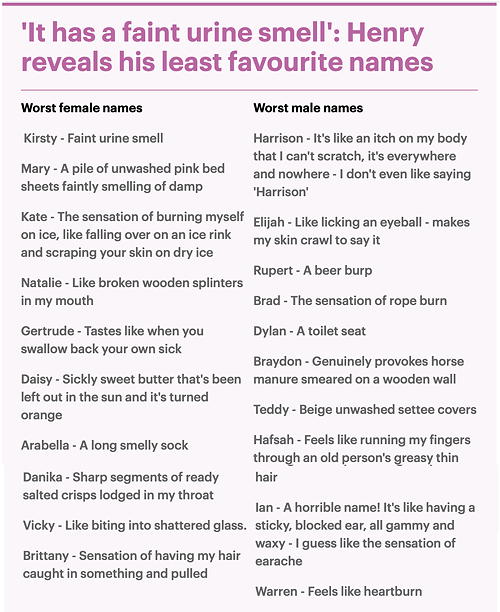

What does your name smell like?

Henry Gray of Newcastle suffers from "lexical-gustatory synaesthesia," which means that he experiences people's names as smells or tastes. He says that the name 'Kirsty' smells of urine, and 'Duncan' is "like a bird dipped in smoky bacon crisps."Makes me wonder what my name would smell like. I'm sure it's not anything good.

More info: Daily Mail

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 05, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Odd Names, Smells and Odors

Smelling the Enemy: The Odortype Detection Program

The U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) launched the "Odortype Detection Program" in 2002. It had two goals:The goal of Phase 2 will be to build a detector that can reliably detect the signature identified in phase 1 with high sensitivity and specificity.

By 2007, DARPA had changed the name of the program to the "Unique Signature Detection Program," but its goals remained essentially the same:

I haven't been able to find out what's become of the program since 2007. Though I'd wager that the U.S. government hasn't completely abandoned the idea since being able to identify people by their smell would be a hard-to-defeat surveillance technology. (Assuming that we all really do have a unique 'odortype' that can't be camouflaged with fragrance or by eating stinky food).

However, I did find a report on the program from 2005 that included the interesting detail that they field-tested the technology on seven sets of twins at Williamsburg, VA and Research Triangle Park, NC:

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jun 12, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Military, Spies and Intelligence Services, Smells and Odors

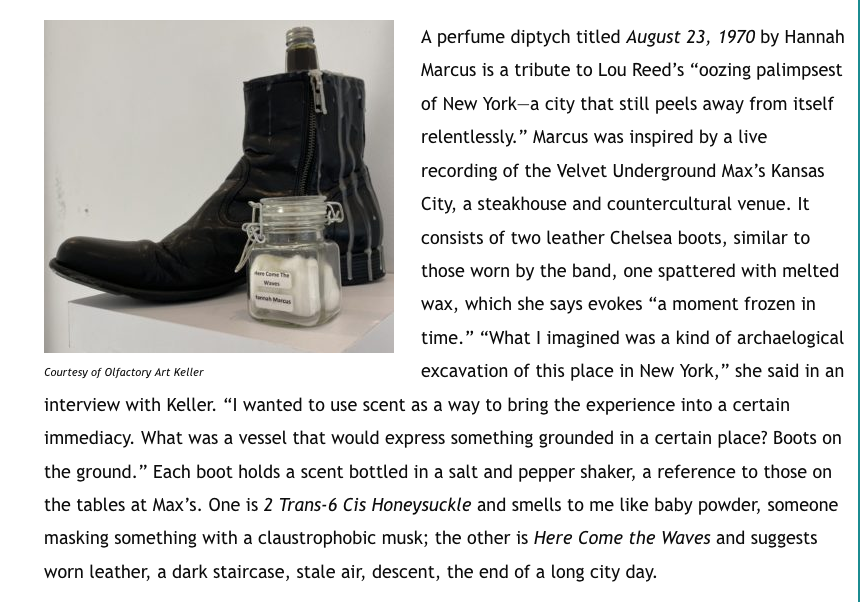

Olfactory Art Keller

A small new gallery in NYC that features smell exhibits.Read about it here.

Their homepage.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Feb 07, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Museums, Smells and Odors

Hand-Sniffing After Handshakes

Research by biologists Noam Sobel and Idan Frumin reveals that after a handshake people frequently lift their hand to their nose and sniff it. The researchers hypothesize that this is to smell the body odor of the other person.As described by Sarah Everts in her recent book The Joy of Sweat:

"When we showed them the videos, many of the subjects were completely shocked and disbelieving," Frumin told me. "Some thought we had doctored the videos - not that we had the computing power or the expertise to do so."

. . . When Frumin now goes to conferences, he sometimes stands back and watches people unconsciously sniffing. "Sometimes I catch myself doing it too. People tell me I've ruined handshakes for them, that they've become very self-conscious about shaking hands, especially with me."

The Weizmann Institute has more info. Sobel and Frumin's article about their research is in the journal eLife Sciences.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Dec 08, 2021 -

Comments (6)

Category: Science, Experiments, Smells and Odors

Follies of the Madmen #508

Was this really ever a problem?

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jun 07, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Annoying Things, Business, Advertising, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, 1940s, Smells and Odors, Moral Panics and Public Hysteria

Best Scents for Sexual Arousal

The article dates from 1997 (The Daily Herald Chicago, Illinois 21 Aug 1997, Thu Page 97), but an actual scientific paper from the same people was posted in 2014. If any WU-vie can cite more recent reasearch, please do so!

Posted By: Paul - Sun May 16, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: 1990s, Twenty-first Century, Smells and Odors, Sex

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |