Eyes and Vision

Bomb Proof Eye Guards

Mechanix Illustrated - Mar 1941

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jul 10, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: War, Weapons, 1940s, Eyes and Vision

Smartphone-Shaped Sunglasses

Part of designer Sinead Gorey's "Phonecore" collection.More info: hmd.com

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 26, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, Eyes and Vision

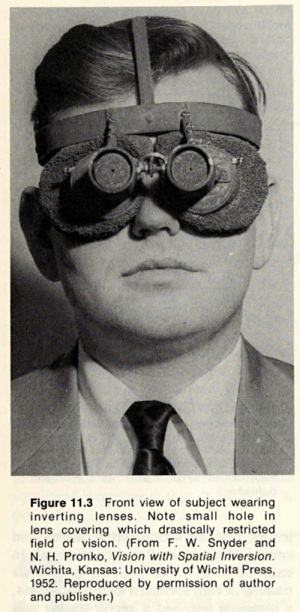

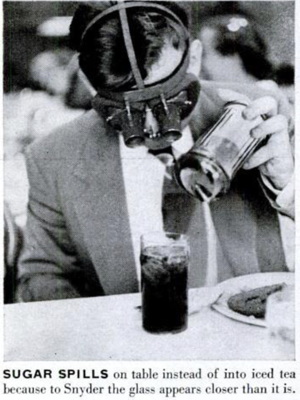

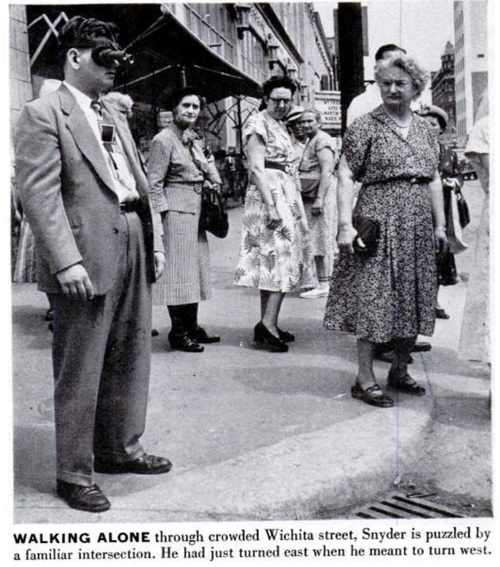

An Upside-Down Experiment

In 1950, graduate student Fred Snyder of the University of Wichita spent 30 days wearing special glasses that inverted his vision. It was part of an experiment designed by Dr. N.H. Pronko, head of the psychology department, to see if a person could adapt to seeing everything upside-down. The answer was that, yes, Snyder gradually adapted to inverted vision. And when the experiment ended he had to re-adapt to seeing the world right-side-up.Snyder and Pronko described the experiment in their 1952 book, Vision with Spatial Inversion. From the book's intro:

Such an experiment is out of the question, of course. Yet another experiment was made: a young man was persuaded to wear inverting lenses for 30 days, and his experiences are reported here. His continued progress, after an initial upset, suggests that new perceptions do develop in the same way as the original perceptions did. Life situations suggest the same thing. Dentists learn to work via a mirror in the patient's mouth until the action is automatic. In the early days of television, cameramen had to "pan" their cameras with a reversed view. Later the image in the camera was corrected to correspond with the scene being panned. The changeover caused considerable confusion to cameramen until they learned appropriate visual-motor coordinations. Fred Snyder, the subject of our upside-down experiment, found himself in a similar predicament, at least for a time.

Images from Life - Sep 18, 1950:

"Graduate student Fred Snyder falling down after removing special eyeglasses that reverse and invert everything he sees. Immediately before removing glasses he rode a bicycle with perfect control along sidewalk in Central Park."

Posted By: Alex - Mon Mar 25, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Experiments, 1950s, Eyes and Vision

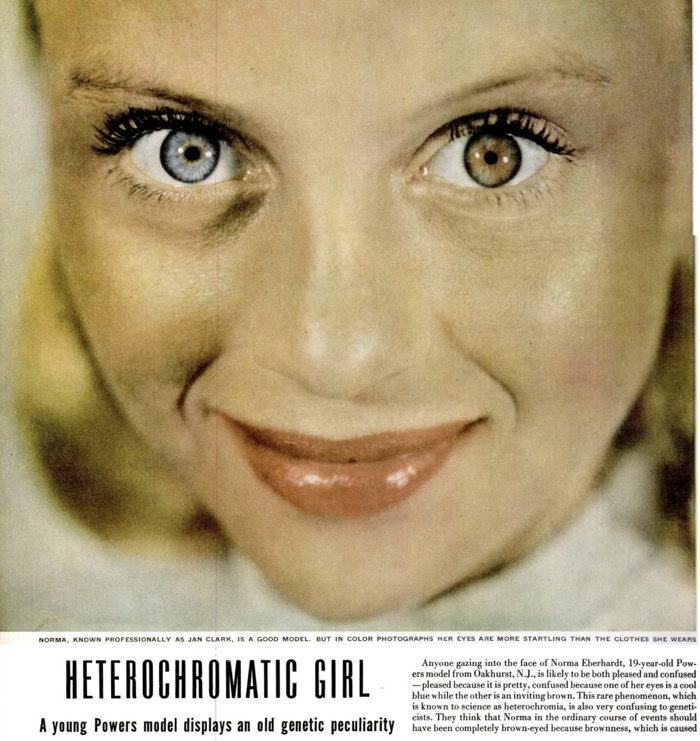

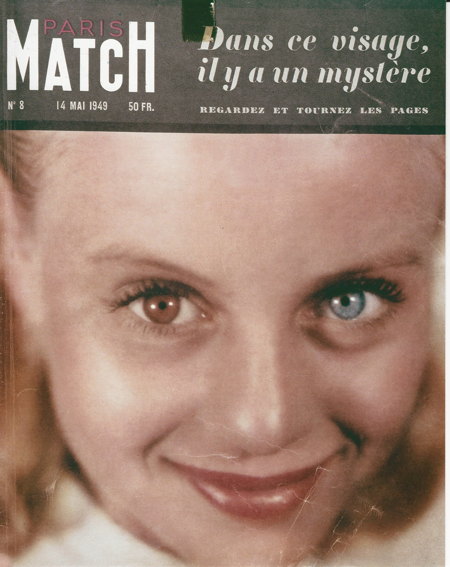

Heterochromatic Girl

AKA Norma Eberhardt. Her heterochromia was reportedly the trait that initially attracted the attention of a photographer, leading to a modeling (and later acting) career.Wikipedia has a list of other actors with heterochromia, but Eberhardt's condition was far more pronounced that most of the other people on the list.

More info: curator's cabinet

Posted By: Alex - Thu Oct 05, 2023 -

Comments (4)

Category: Actors, Eyes and Vision

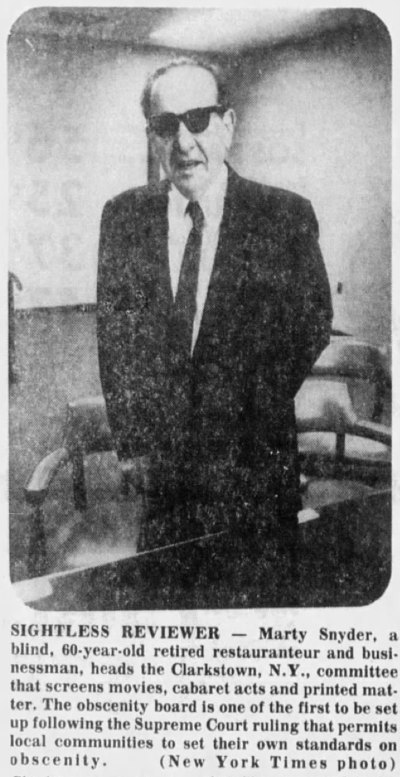

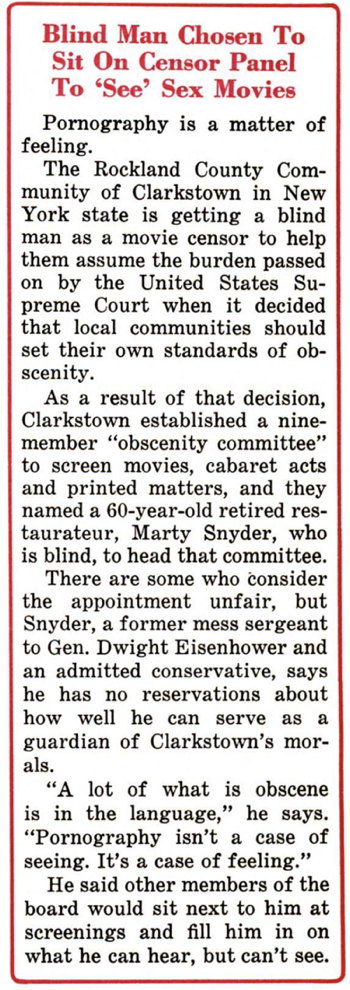

Marty Snyder, the blind movie censor

Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said, when asked to define pornography, "I know it when I see it."Marty Snyder couldn't see it, but he figured he would know it anyway, especially if the person sitting next to him filled him in on what he was missing.

Snyder ended up serving on the Clarkstown censorship panel for less than a year because he died of a stroke in 1974.

South Mississippi Sun - Oct 25, 1973

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 25, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Censorship, Bluenoses, Taboos, Prohibitions and Other Cultural No-No’s, 1970s, Eyes and Vision

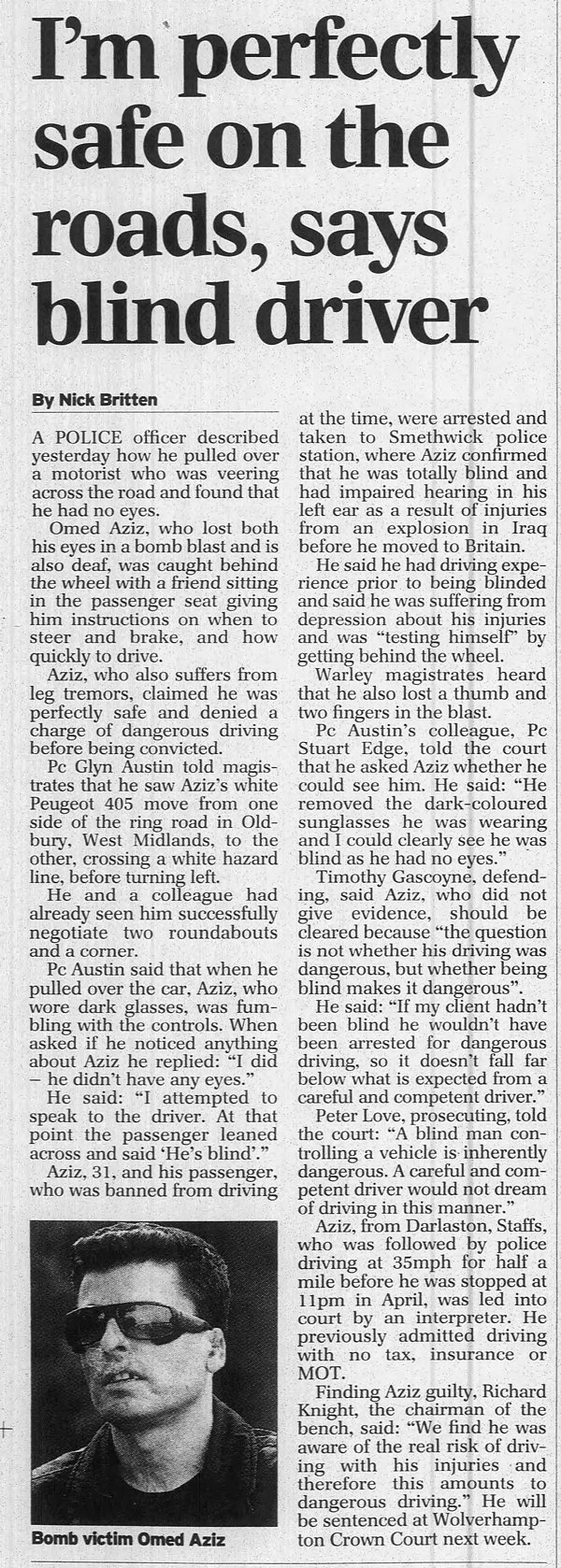

Driving Blind

London Daily Telegraph - Sep 5, 2006

Posted By: Alex - Tue Nov 29, 2022 -

Comments (5)

Category: 2000s, Eyes and Vision, Cars

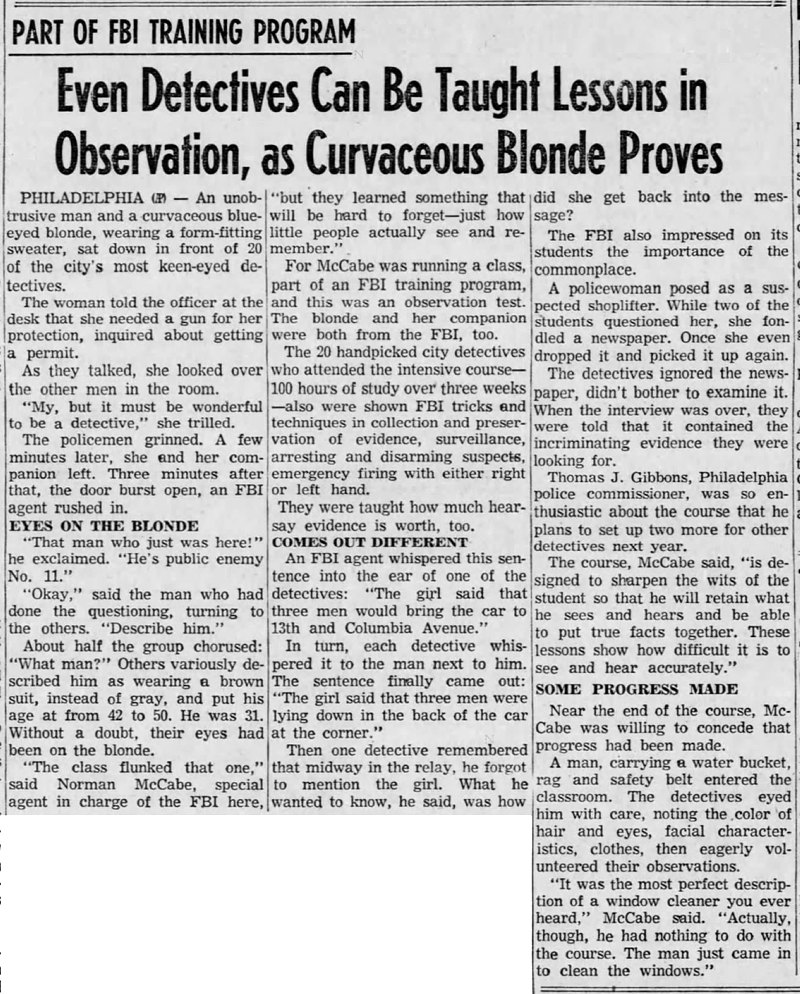

The Blonde And Her Companion

Back in the 1950s, the FBI used "a curvaceous blue-eyed blonde, wearing a form-fitting sweater" to help train its agents to improve their powers of observation. The lesson was that if they spent too much time looking at her, they might miss other important details, such as her companion, "public enemy No. 11."Reminds me of the "woman in the red dress" featured in the agent-training-program scene in The Matrix. I wonder if the Wachowskis had heard of the "blonde and her companion" test.

San Bernardino County Sun - Dec 4, 1955

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 26, 2022 -

Comments (8)

Category: Police and Other Law Enforcement, 1950s, Eyes and Vision

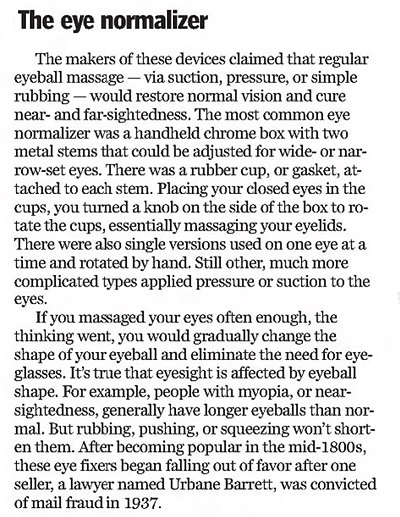

The Barrett Eye Normalizer

Perfect vision through eyeball massage. At least, that was the claim.

Hearst's International-Cosmopolitan - Oct 1926

Source: American Artifacts

Boston Sunday Globe - Oct 8, 2017

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 23, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Frauds, Cons and Scams, Eyes and Vision

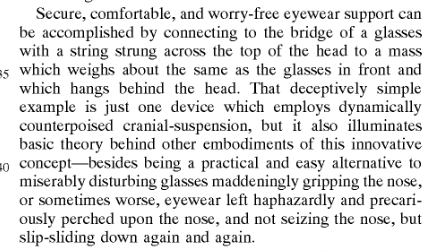

Counterpoised Cranial Support for Eyewear

Full patent here (with other devices included!).

Posted By: Paul - Sun Sep 25, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Ridiculousness, Foolishness, Public Ridicule, Silliness, Goofiness and Dumb-looking, 2000s, Eyes and Vision

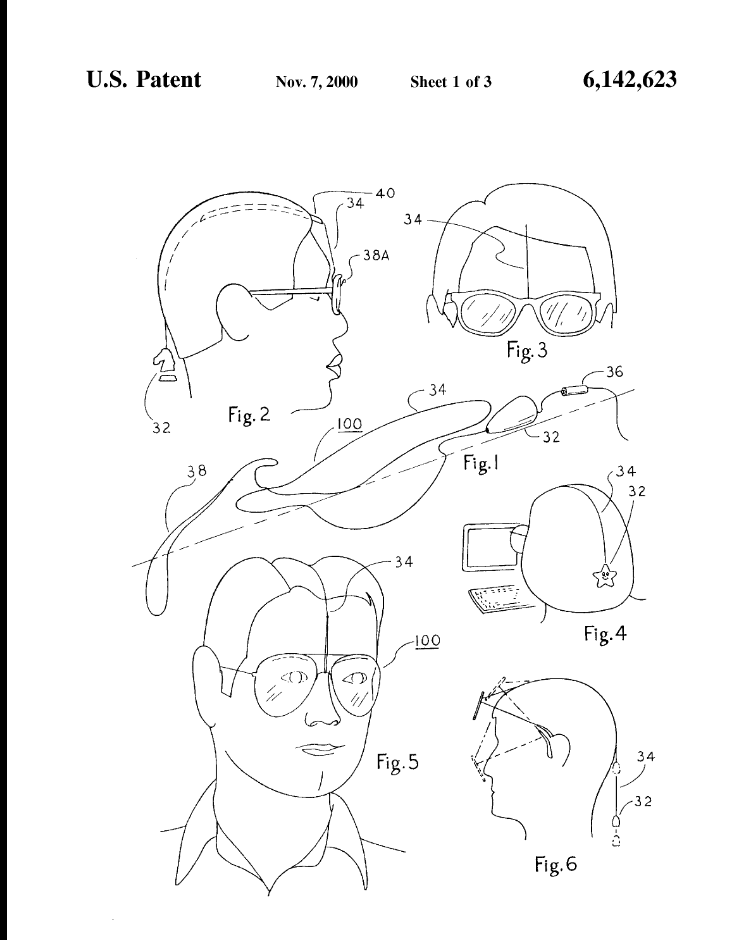

The New Eyelashes

Posted By: Alex - Wed Sep 21, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, 1930s, Eyes and Vision

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |