Psychology

The Shrink

Poetry of the insane?Are you nuts? Are you nuts? Have you lost your guts?

Why do you think you are nuts?

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 16, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Music, Television, Psychology, 1980s, Mental Health and Insanity

The Psychology of Doorknobs

Marketing psychologist Ernest Dichter argued that home buyers place great emphasis on the feel of doorknobs when looking at a house, because "The doorknob offers the only way you can caress a house."Clipping from "Emotion brings out the buying power," by Roger Ricklefs in The Sunbury Daily Item (Nov 21, 1972):

Why do big doorknobs help sell a house? Why do some men become irrationally hostile when their sock drawers are empty? Such are the questions that intrigue researchers like Mr. Dichter...

in the past two or three years Du Pont, Alcoa, General Mills, Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive, Johnson & Johnson, Schenley Industries and dozens of other well-known companies have commissioned studies from Mr. Dichter's Institute for Motivational Research here. The institute has annual volume of $600,000 and profits of $80,000 to $100,000.

Many people find Dichter's interpretations far-fetched. But people who accept the basic beliefs of modern psychologists find them quite plausible.

The psychologist says he's found that even a commonplace object like a doorknob has a surprising emotional significance to buyers.

"The doorknob offers the only way you can caress a house; you can't caress the walls," he says. "The way a product fills a hand is very important. How a handle does this will make an engineer prefer one technical product over another — and he doesn't even realize it," Mr. Dichter says.

During part of a baby's embryonic development, the thumb fills the palm of the hand, Mr. Dichter says. The new-born infant thus exhibits a strong desire to grasp objects, possibly to fill the palm of the hand again, the psychologist adds.

As he sees it, the same instinct later prompts a sub-conscious tendency to judge a house by its doorknob or a tool by its handle. Mr. Dichter says these findings and theories prompted a California lockmaker to enlarge the doorknobs it manufactured.

Even men's socks can inspire passion, Mr. Dichter asserts. "We find that an empty sock drawer is a symbol of an empty heart," Mr. Dichter said in a study for Du Pont's hosiery section. "When the husband finds that his sock drawer is not overflowing, he interprets his wife's neglect as symptomatic of her lack of consideration, concern and love."

source: The Advertising Age by John McDonough

San Francisco Examiner - Sep 2, 1966

More info: Ernest Dichter (wikipedia)

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 29, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Architecture, Psychology

How to Live With Yourself … or … What to Do Until the Psychiatrist Comes

Standup from a psychiatrist. His Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jun 23, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Humor, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Psychology, 1960s

Eating ramen as restaurant burns

One of the minor weird-news themes we track here on WU is that of people who are so engrossed in whatever they're doing that they're unfazed by the building burning around them. (See the previous posts "Can't miss the show", "Unfazed by fire", and "The Smoke-Filled Room").The phenomenon was seen recently at a Ramen Jiro restaurant in Tokyo. As thick smoke began to fill the restaurant, the diners inside simply continued to eat their noodles as if nothing was wrong. More info: SoraNews24

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 07, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Restaurants, Psychology

No TV for a year

Back in the early 1970s, a German research group called "The Society for Rational Psychology" challenged 184 people (all regular TV watchers) to go without TV for a year.. with financial incentives to encourage them to stick to the plan.Briefly all went well, but then things quickly began to go downhill. Frustration grew. The people started to become moody and aggressive. After five months they were all back to watching TV.

The lesson the researchers concluded: "people who watch television regularly are likely to become so addicted they can no longer be happy without it."

What would they conclude about the Internet?

Of course, the study probably needs to be taken with a grain of salt because I can't find any info about this Society for Rational Psychology. Was it some kind of market research group? Nor can I find the write-up from the study itself. Just lots of references to the study in the media.

Buffalo Evening News - May 8, 1972

Posted By: Alex - Fri May 17, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Addictions, Television, Psychology, 1970s

The doctor who made rats go insane

Dr. Norman Maier is pretty much unknown today, but Wikipedia notes that his research "received extensive publicity in its day." That research involved making rats go insane.

The cause of man's mental suffering identified: not being given his breakfast promptly at 7 am.

Thus a man who is "conditioned" to expect his breakfast promptly at 7 o'clock in the morning and does not get it may develop a nervous disorder if his wife fails to provide it at that time for many mornings in succession.

Detroit Free Press - Jan 1, 1939

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 13, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Animals, Psychology, 1930s

Aspirin-Induced Musical Hallucinations

A 1985 letter in the New England Journal of Medicine reported the unusual case of a 70-year-old woman who kept hearing music playing in her head, particularly the song "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling." After ruling out other possible causes, her doctor eventually suspected the music might be due to the high doses of aspirin she was taking. And sure enough, when she reduced her aspirin intake, the music stopped.I would never have thought that aspirin could cause musical hallucinations!

Tampa Bay Times - Apr 2, 1986

The letter itself is behind a paywall, but I was able to find a brief article that the woman's doctor (James R. Allen) wrote about the case in the magazine of the Minnesota Medical Association.

Minnesota Medicine - Nov 2008

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 01, 2024 -

Comments (5)

Category: Medicine, Music, Psychology

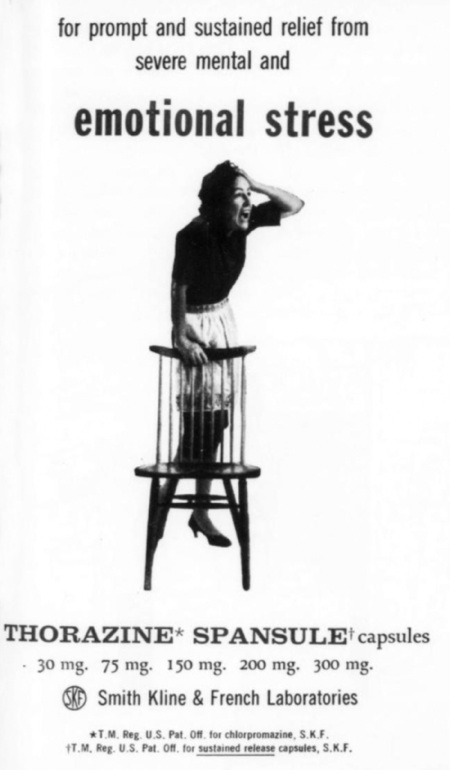

For relief of emotional stress

For housewives on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

Medical Economics - Mar 2, 1959

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 20, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medicine, Psychology, 1950s

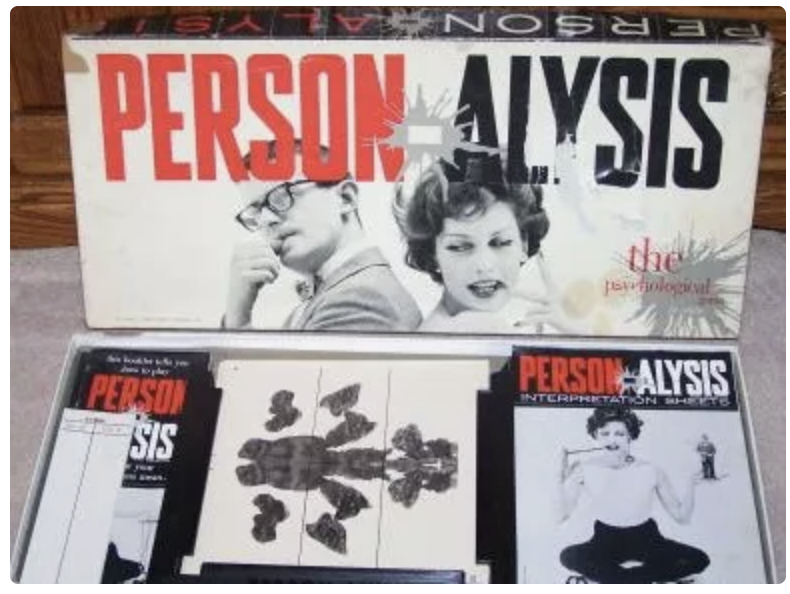

Person-Alysis Game

Reveal which member of the family has an Oedipus Complex! Who's a sociopath? Good fun!The entry at Board Game Geek.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Mar 14, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Bad Habits, Neuroses and Psychoses, Games, Hobbies and DIY, Psychology, 1950s

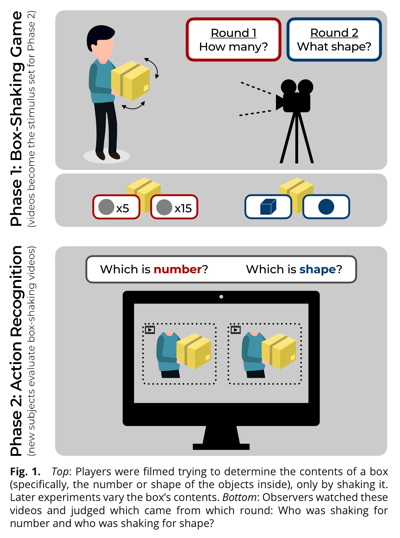

The science of shaking Christmas presents

Researchers at the University of Michigan have been studying people shaking boxes in order to shed light on "epistemic action understanding." Or rather, "Can one person tell, just by observing another person’s movements, what they are trying to learn?"In other words, as you watch someone shake a box, can you figure out what information they're trying to gather about the contents of the box (i.e. the shape or quantity of things in it)?

More info: "Seeing and understanding epistemic actions"

Posted By: Alex - Sat Dec 30, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Science, Experiments, Psychology, Christmas

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |