Medicine

Recurrent Sudden Death

One of the stranger medical problems a person could suffer from is "recurrent sudden death." In fact, one might think it impossible to suffer from such a problem. However, the term appears fairly often in medical literature. A few examples:

Atlas of Heart Diseases - Arrhythmias : electrophysiologic principles, 1996

New England Journal of Medicine - June 3, 1982

I think, though I'm not entirely sure, that "sudden death" is being used as a synonym for "cardiac arrest." Doctors are aware that the term "recurrent sudden death" sounds absurd. Stedman's Medical Dictionary (2006) advises them not to use it:

And yet the term continues to appear.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 15, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, Medicine

Headache Hanger

Full patent here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed May 15, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Medicine, 1910s, Head

Aspirin-Induced Musical Hallucinations

A 1985 letter in the New England Journal of Medicine reported the unusual case of a 70-year-old woman who kept hearing music playing in her head, particularly the song "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling." After ruling out other possible causes, her doctor eventually suspected the music might be due to the high doses of aspirin she was taking. And sure enough, when she reduced her aspirin intake, the music stopped.I would never have thought that aspirin could cause musical hallucinations!

Tampa Bay Times - Apr 2, 1986

The letter itself is behind a paywall, but I was able to find a brief article that the woman's doctor (James R. Allen) wrote about the case in the magazine of the Minnesota Medical Association.

Minnesota Medicine - Nov 2008

Posted By: Alex - Wed May 01, 2024 -

Comments (5)

Category: Medicine, Music, Psychology

Fish Surgery

This is not a topic I had given much thought to, before encountering this report from 1955.Then I found more-current info.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Apr 25, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medicine, Fish, 1950s, Twenty-first Century

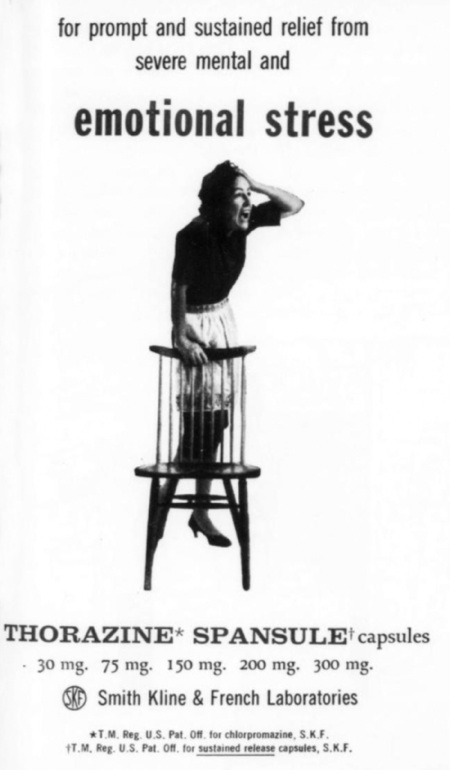

For relief of emotional stress

For housewives on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

Medical Economics - Mar 2, 1959

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 20, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medicine, Psychology, 1950s

A case of hypervaccination

The Lancet reports on the case of a 62-year-old German man who received 217 Covid vaccinations over a period of 29 months. That works out to getting vaccinated approximately every four days.When I got the Covid vaccine I felt for a day like I'd been run over by a truck. The German hypervaccinator, on the other hand, felt no vaccine-related side effects.

Presumably the guy thought that all the vaccinations would give him super-immunity. When medical professionals realized what he had done, however, they were more worried that the opposite would happen — that he would build up "immune tolerance" and be more susceptible to Covid, not less. But when they checked him out, he seemed just fine.

More info: arstechnica.com

Posted By: Alex - Thu Mar 07, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Medicine

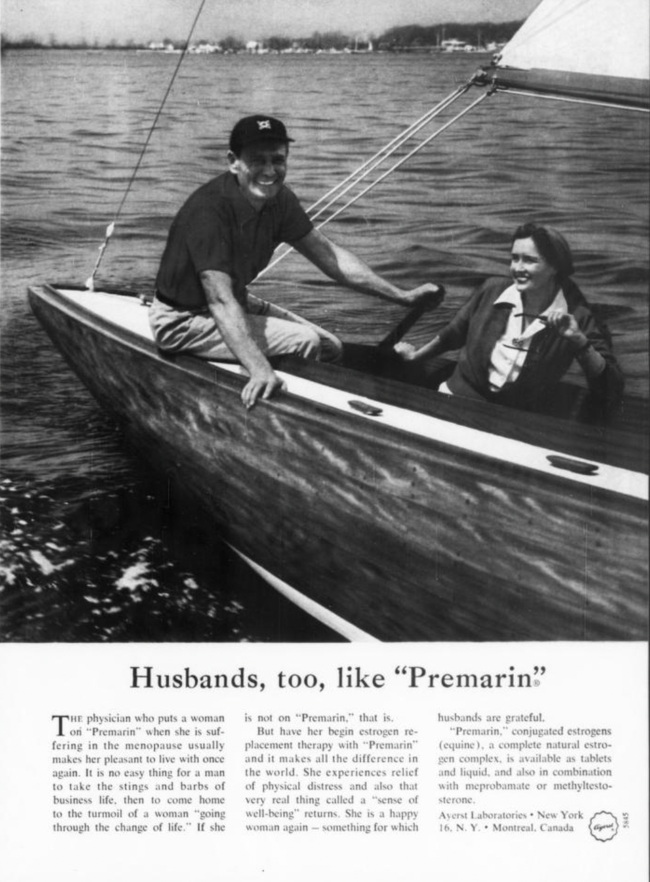

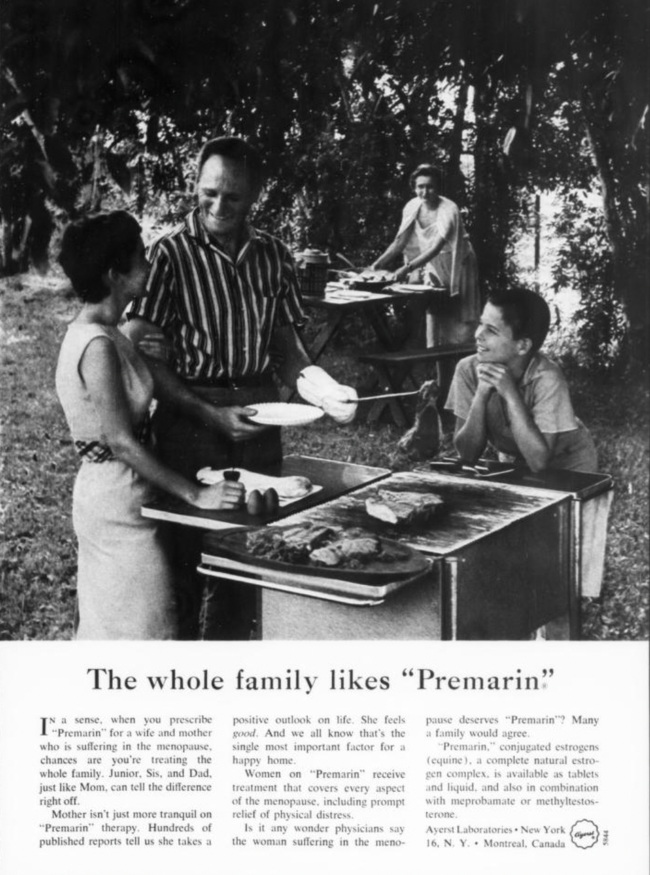

Husbands too like Premarin

Make your wife pleasant again with Premarin!By the 1990s, Premarin had become the most frequently prescribed medication in the United States. Now, according to Wikipedia, it's down to number 283.

The word 'Premarin' is a portmanteau of PREgnant MAre uRINe.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Mar 05, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medicine, Advertising, Husbands, Wives, 1950s

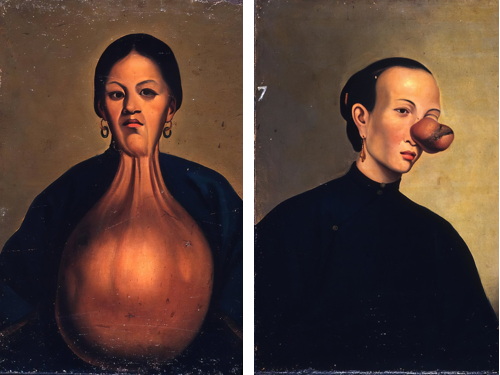

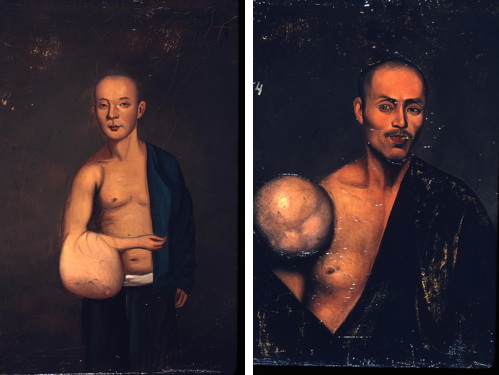

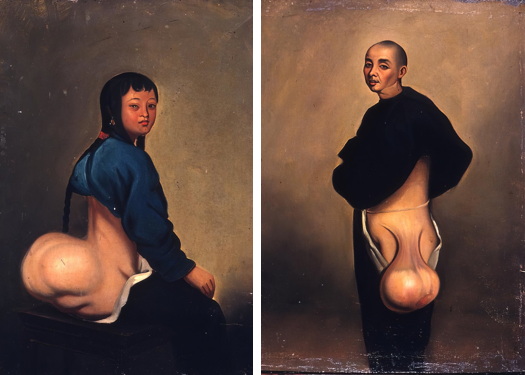

Tumor Paintings

In 1834, Dr. Peter Parker obtained a medical degree from Yale University and then traveled to China as a medical missionary. There he commissioned Chinese painter Lam Qua to make portraits of patients at the Canton Hospital who had large tumors. Yale now has 86 of these portraits in its collection.Peter Parker seems to have been a fairly common name before it became permanently associated with Spider-Man.

More info: Yale University Library

via Design You Trust

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 31, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Medicine, Nineteenth Century

Follies of the Madmen #582

Posted By: Paul - Sun Nov 26, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Anthropomorphism, Medicine, Advertising, Stop-motion Animation, 1960s

AI and the ruler

I've seen this cautionary tale about putting too much faith in AI referred to in several places. It involves an AI program that had seemed to have "reached a level of accuracy comparable to human dermatologists at diagnosing malignant skin lesions." Venturebeat.com tells the rest:I tracked down the original source of this story to an Oct 2018 article in the

Journal of Investigative Dermatology: "Automated Classification of Skin Lesions: From Pixels to Practice":

Posted By: Alex - Thu Aug 17, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Medicine, AI, Robots and Other Automatons

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |