Literature

Towers Open Fire

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jul 20, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Jabberwocky, Scat Singing, Nonsense Verse and Glossolalia, Literature, Movies, Surrealism, 1960s

Patience Worth

Pearl Lenore Curran wrote four novels and many poems, but claimed that they had all been dictated to her by a woman named Patience Worth who had lived over two hundred years earlier. So, A body of work that was literally ghost-written.Info from Superstition and the Press (1983) by Curtis MacDougall:

Note: the Patience Worth poems were included in Braithwaite's 1918 anthology, not the 1917 one.

More info: Wikipedia, Smithsonian magazine

You can also find the Patience Worth novels on archive.org.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 12, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Literature, Books, Poetry, Paranormal

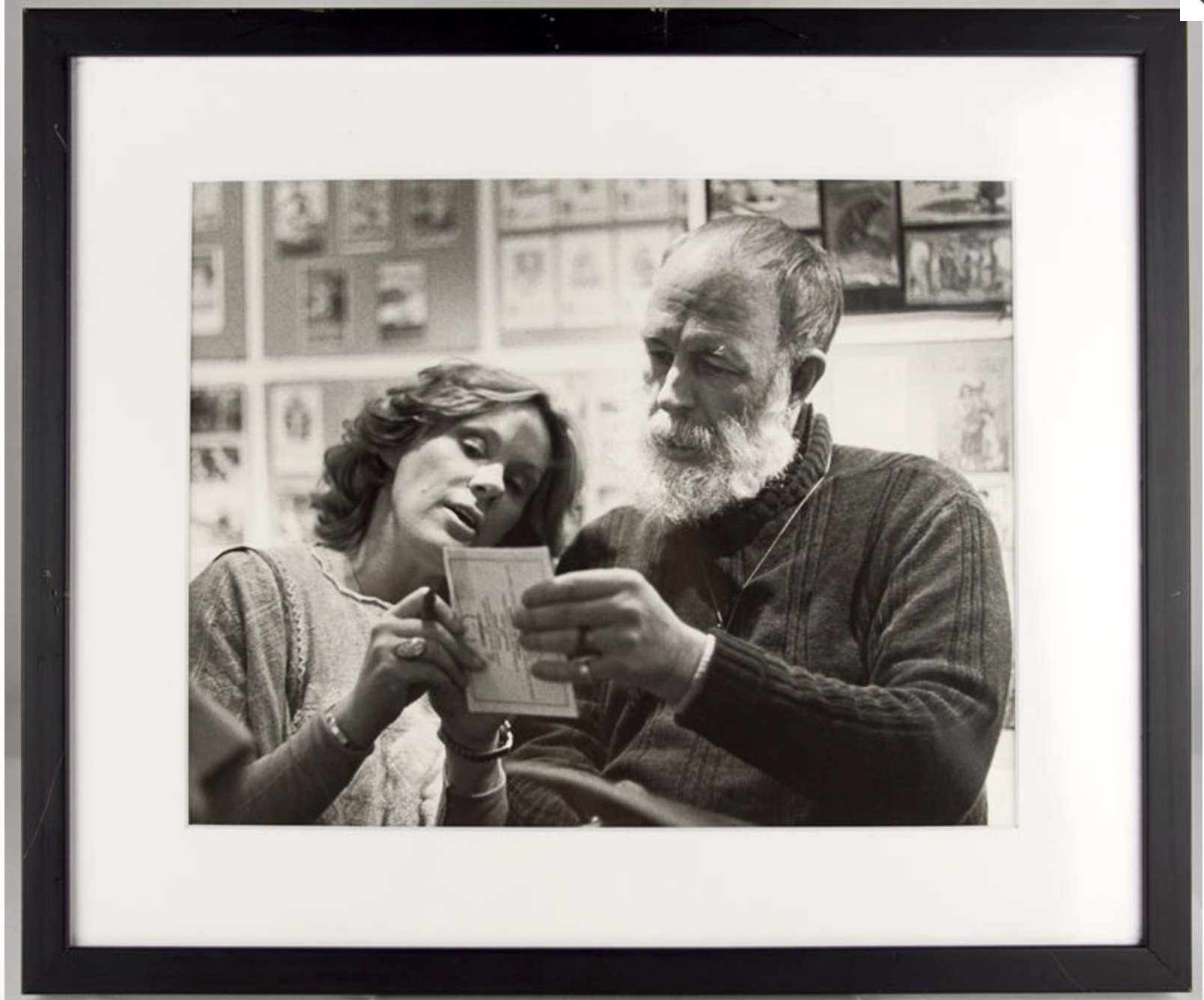

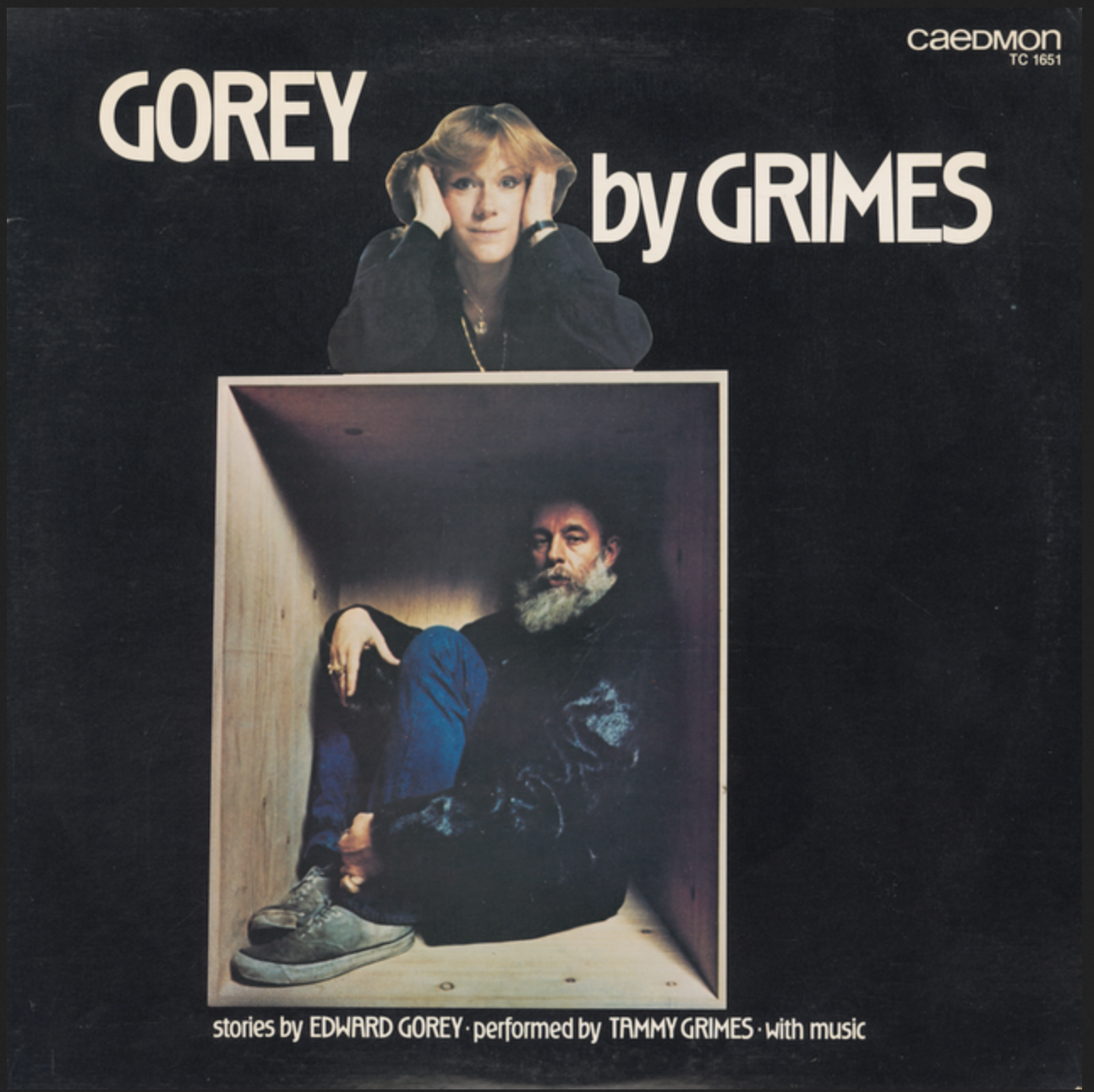

Gorey by Grimes

There are other tracks from this album on YouTube, but this cut should give you the general idea.Tammy Grimes on Wikipedia.

Edward Gorey on Wikipedia.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Dec 03, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Death, Literature, Music, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Children

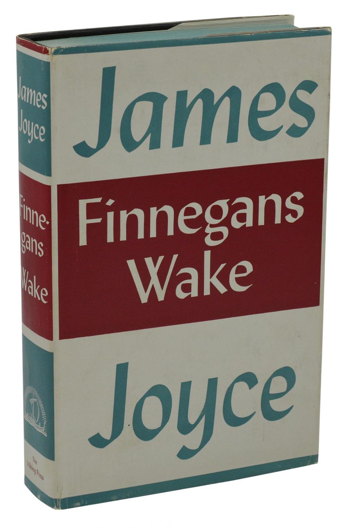

How to read (and finish) Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake is a notoriously difficult book to read. But Gerry Fialka and his book group figured out a way to do it. They read it very slowly. Very, very slowly. They read two pages a month, and then would meet to discuss those pages.They started doing this in 1995, and a few weeks ago (Oct 2023) they reached the end. So it took them 28 years, but they finished the book. Now they're starting over.

More info: Orange County Register

Related post: The coach with the six insides

Posted By: Alex - Mon Oct 30, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Literature, Books

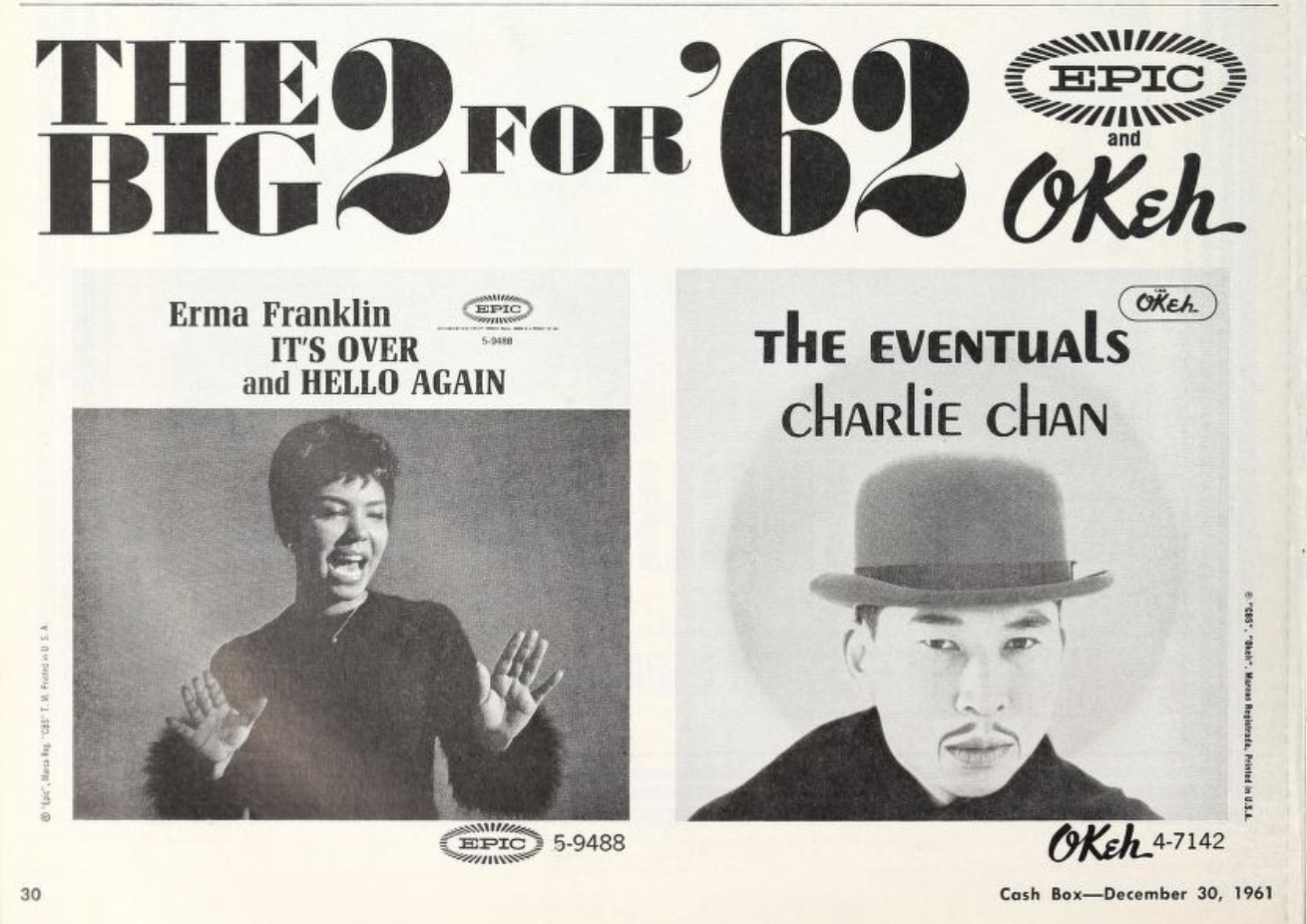

The Eventuals, “Charlie Chan”

Posted By: Paul - Mon Oct 02, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Literature, Movies, Music, Stereotypes and Cliches, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, 1960s, Asia

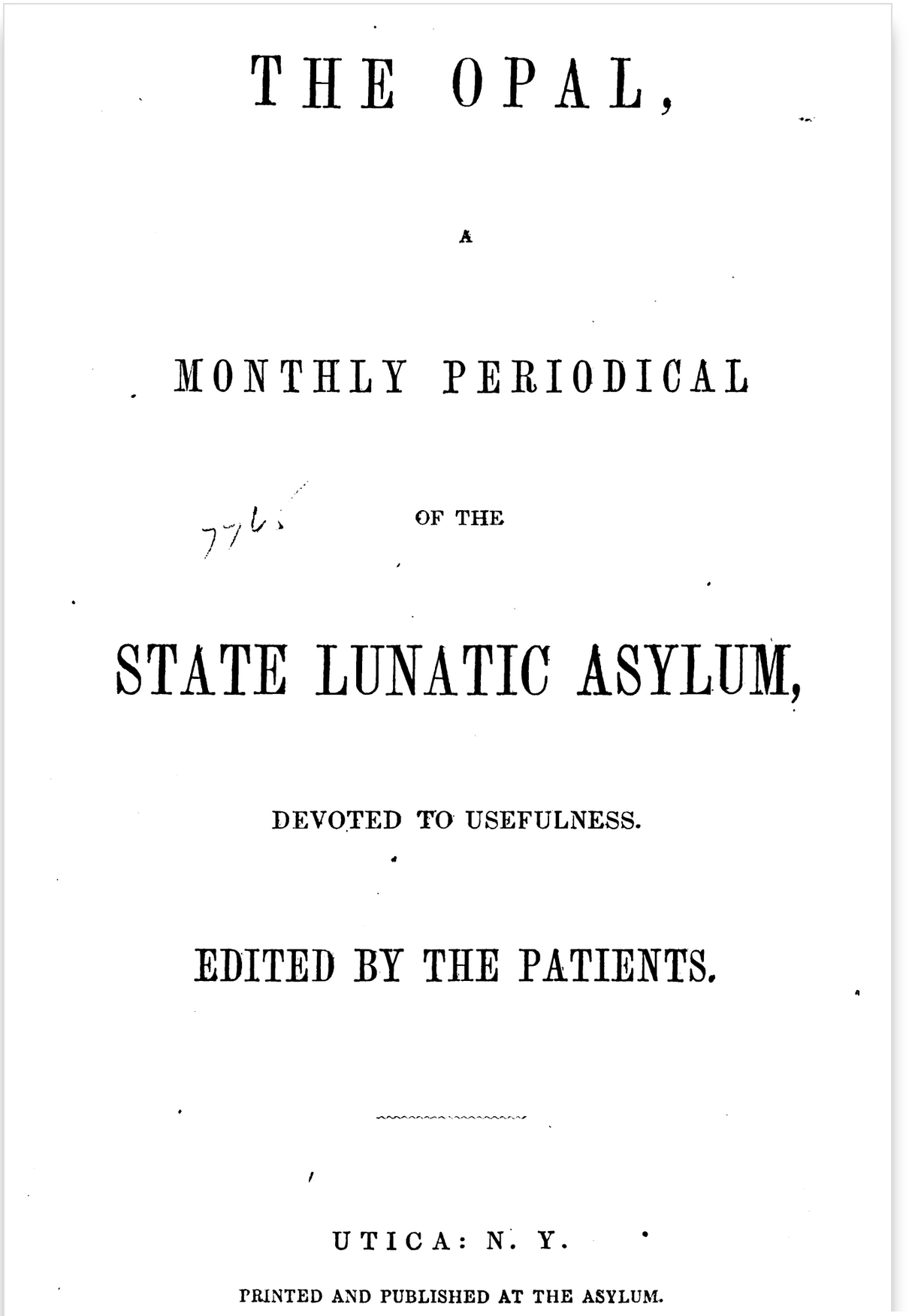

The Opal

Read it here. Spoiler: it's all very bland.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Sep 30, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Literature, Magazines, Nineteenth Century, Mental Health and Insanity

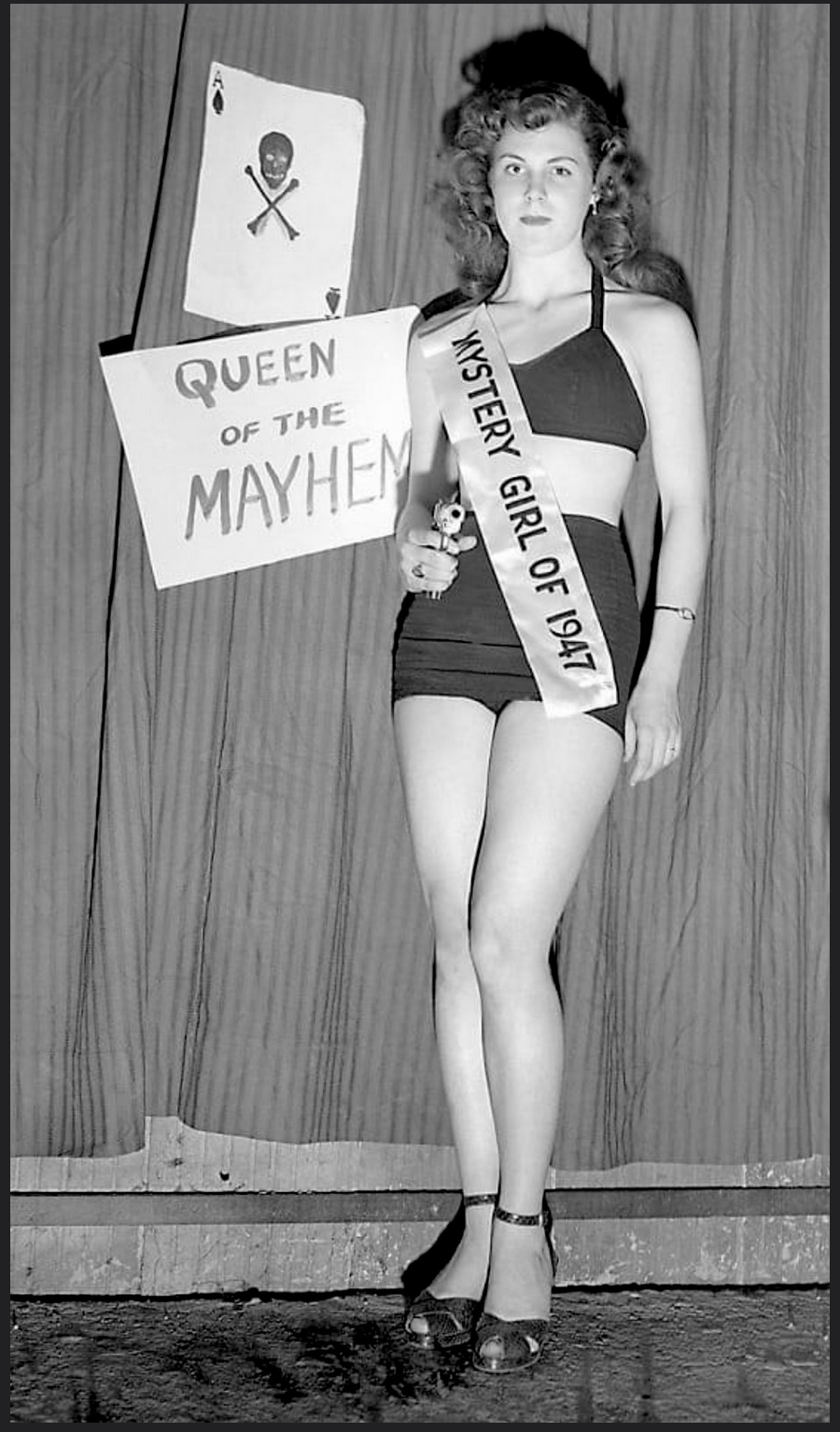

Mystery Girl of 1947

Pulp International reveals:The Mystery Writers of America, which was founded in 1945 in New York City and soon expanded to other locations, in its early years used to throw what they called a Clues Party. In November 1947 the party was in Chicago, and the MWA awarded the title of Mystery Girl to the woman who performed best in a scream test—as opposed to screen test. Four contestants—Marybeth Prebis, Betty Rosboro, Bobby Jo Rodgers, and Portia Kubin—let fly with their most bloodcurdling screams, and the winner was Kubin, above.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Sep 23, 2023 -

Comments (4)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Literature, Books, 1940s, Screams, Grunts and Other Exclamations

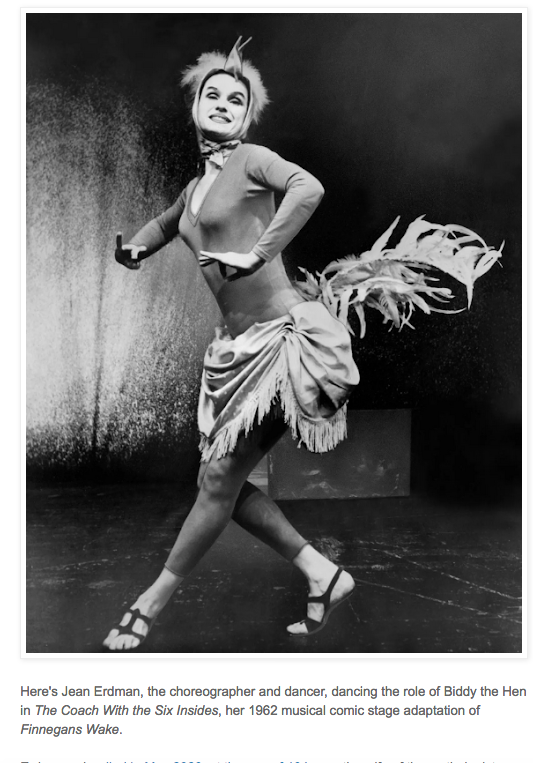

The Coach With the Six Insides

James Joyce's novel FINNEGANS WAKE is notorious for its undecipherability. But somehow Jean Erdman, wife of mythologist Joseph Campbell (himself a Joyce expert) decided the book could be transformed into a dance.See video after snapshot.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Sep 06, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Literature, Music, Unsolved Mysteries, 1960s, Dance

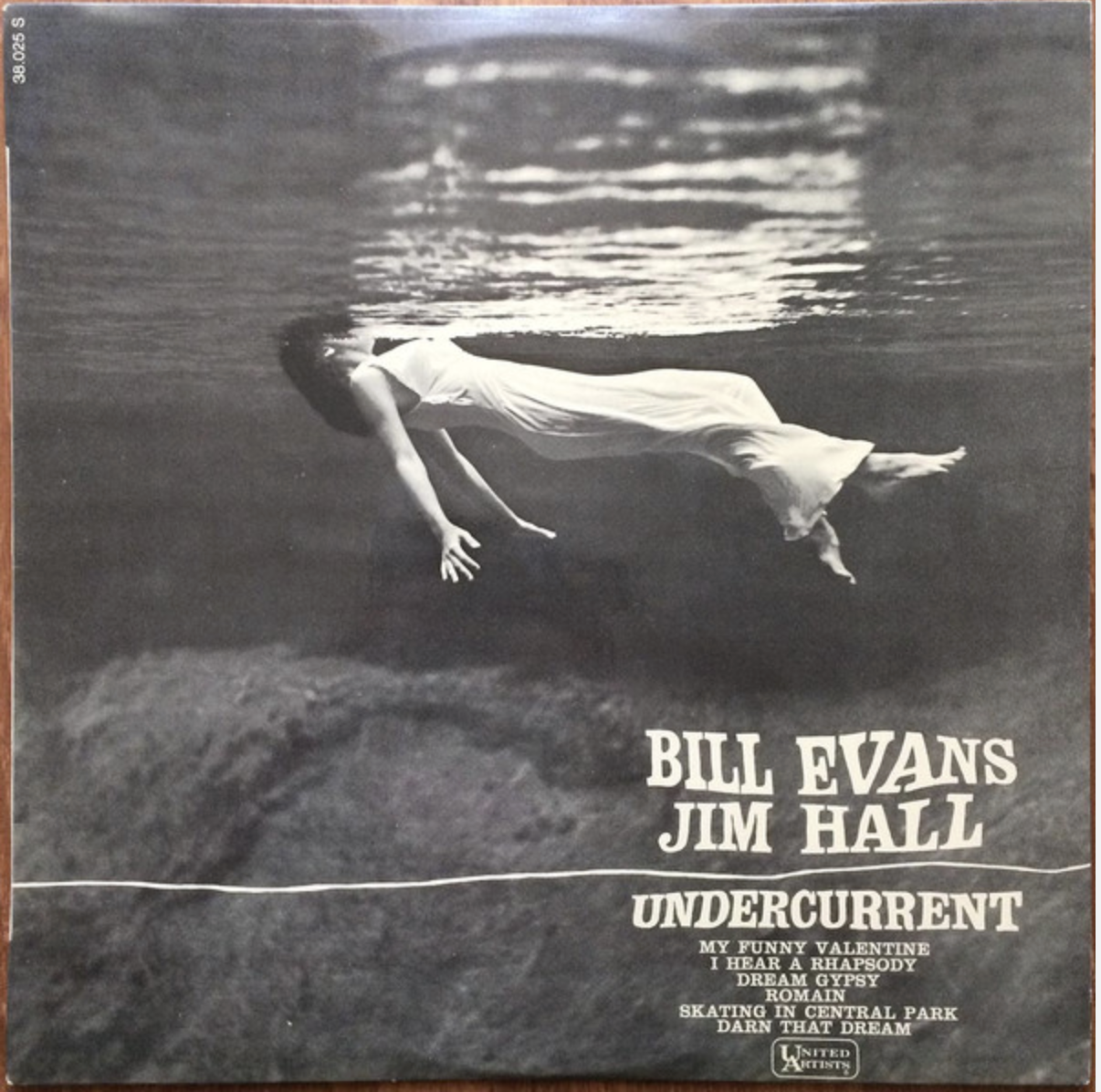

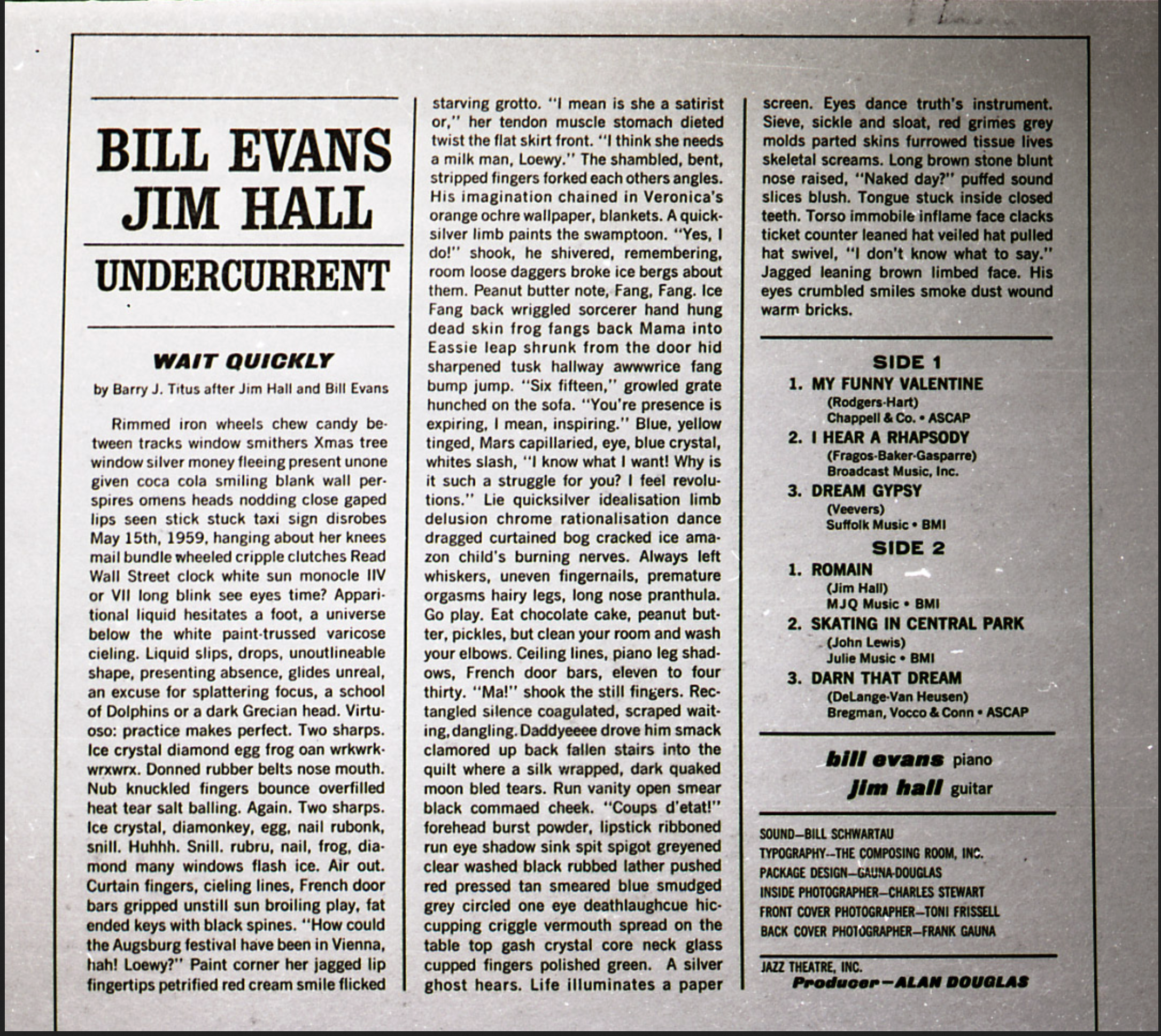

Most Inscrutable Liner Notes Ever

The Wikipedia page for the album.

I have taken the liberty of breaking the text into random paragraphs, to ease your perusal.

Who was the author, Barry Titus? We find record of him under his wife's Wikipedia page.

WAIT QUICKLY by Barry J. Titus after Jim Hall and Bill Evans

Rimmed iron wheels chew candy between tracks window smithers Xmas tree window silver money fleeing present unone given coca cola smiling blank wall perspires omens heads nodding close gaped lips seen stick stuck taxi sign disrobes May 15th, 1959. hanging about her knees mail bundle wheeled cripple clutches Read Wall Street clock white sun monocle IIV or VII long blink see eyes time? Apparitional liquid hesitates a foot, a universe below the white paint-trussed varicose cieling. Liquid slips, drops, unoutlineable shape, presenting absence, glides unreal, an excuse for splattering focus, a school of Dolphins or a dark Grecian head.

Virtuoso: practice makes perfect. Two sharps. Ice crystal diamond egg frog oan wrkwrk-wrxwrx. Donned rubber belts nose mouth. Nub knuckled fingers bounce overfilled heat tear salt balling. Again. Two sharps. Ice crystal, diamonkey, egg, nail rubonk, snill. Huhhh. Snill. rubru, nail, frog, diamond many windows flash ice. Air out. Curtain fingers, cieling lines, French door bars gripped unstill sun broiling play, fat ended keys with black spines.

"How could the Augsburg festival have been in Vienna, hah! Loewy?" Paint corner her jagged lip fingertips petrified red cream smile flicked starving grotto. "I mean is she a satirist or," her tendon muscle stomach dieted twist the flat skirt front. "I think she needs a milk man, Loewy." The shambled, bent, stripped fingers forked each others angles. His imagination chained in Veronica's orange ochre wallpaper, blankets. A quicksilver limb paints the swamptoon. "Yes, I do!" shook, he shivered, remembering, room loose daggers broke ice bergs about them. Peanut butter note, Fang, Fang. Ice Fang back wriggled sorcerer hand hung dead skin frog fangs back Mama into Eassie leap shrunk from the door hid sharpened tusk hallway awwwrice fang bump jump.

"Six fifteen," growled grate hunched on the sofa. "You're presence is expiring, I mean, inspiring." Blue, yellow tinged, Mars capillaried, eye, blue crystal, whites slash, "I know what I want! Why is it such a struggle for you? I feel revolutions." Lie quicksilver idealisation limb delusion chrome rationalisation dance dragged curtained bog cracked ice amazon child's burning nerves. Always left whiskers, uneven fingernails, premature orgasms hairy legs, long nose pranthula.

Go play. Eat chocolate cake, peanut butter, pickles, but clean your room and wash your elbows. Ceiling lines, piano leg shadows, French door bars, eleven to four thirty. "Ma!" shook the still fingers. Rectangled silence coagulated, scraped waiting, dangling. Daddyeeee drove him smack clamored up back fallen stairs into the quilt where a silk wrapped, dark quaked moon bled tears. Run vanity open smear black commaed cheek. "Coups d'etat!" forehead burst powder, lipstick ribboned run eye shadow sink spit spigot greyened clear washed black rubbed lather pushed red pressed tan smeared blue smudged grey circled one eye deathlaughcue hiccupping criggle vermouth spread on the table top gash crystal core neck glass cupped fingers polished green.

A silver ghost hears. Life illuminates a paper screen. Eyes dance truth's instrument. Sieve, sickle and sloat, red grimes grey molds parted skins furrowed tissue lives skeletal screams. Long brown stone blunt nose raised, "Naked day?" puffed sound slices blush. Tongue stuck inside closed teeth. Torso immobile inflame face clacks ticket counter leaned hat veiled hat pulled hat swivel, "I don't know what to say." Jagged leaning brown limbed face. His eyes crumbled smiles smoke dust wound warm bricks.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jul 08, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Literature, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Surrealism, 1960s

FINNEGANS WAKE on Audio

Ease yourself into this famously baffling masterpiece by listening to Joyce himself proclaim a passage. Then queue up the whole book on your car's sound system for a relaxing commute!

Posted By: Paul - Thu Feb 23, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Literature, Unexplained Historical Enigmas, 1920s, Cacophony, Dissonance, White Noise and Other Sonic Assaults

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |