Insects and Spiders

Dr. Robert Lopez Infects Himself with Cat Ear Mites

Yesterday, Alex regaled us with the report of a fellow who swallowed a giraffe liver parasite in the pursuit of knowledge.Well, here's another scientist who wanted to learn what cats went through with an ear mite infestation, choosing to insert them into his own ears.

There's a tremendous long piece about him here, even including a video!

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jul 24, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Hobbies and DIY, Insects and Spiders, Mad Scientists, Evil Geniuses, Insane Villains, Science, Cats, 1990s

Bipartite Insect-Excluding Airlock

This seems like a lot of work just to keep a few flies out of your house. And do insects really dislike entering darkened rooms?Full patent.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jun 24, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Domestic, Insects and Spiders, Patents, 1910s

The Tarantula Wronged

In 1972, arachnidist John A. L. Cooke undertook to defend the reputation of tarantulas. Text from the Saskatoon Star-Phoenix (Nov 2, 1972):"I wouldn't let my 4-year-old son keep one as a pet if they were," he said.

Their bad name, he added, can be traced to the region around Taranto, in southern Italy, from which they take their name. This is the habitat of the true, or European Tarantul, whose bite was said to induce tarantism.

Webster's New International Dictionary defines tarantism as: "A nervous affection characterized by melancholy, stupor, and an uncontrollable desire to dance."

The traditional treatment was to encourage the victim to dance wildly until the effects of the poison wore off. Thus evolved the wild Neapolitan folk dance, the tarantella. According to Cooke, who is writing an article on the subject for Natural History magazine, musicians wandered through the fields at harvest time, ready to offer their services to a victim of tarantula bite.

Saskatoon Star-Phoenix - Nov 2, 1972

In his subsequent Natural History article, Cooke then revealed that it was probably black widows that had been biting the people around Taranto back in the Middle Ages. The tarantulas had been unfairly maligned:

"Despite their formidable appearance, North American tarantulas are a serious threat only to their prey—beetles and grasshoppers."

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jun 22, 2024 -

Comments (7)

Category: Insects and Spiders

Follies of the Madmen #594

Squished passenger and allusion to an insect's posterior: winning strategy?

Posted By: Paul - Tue Apr 30, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Mental and Physical Unease and Discomfort, Advertising, 1960s, Cars

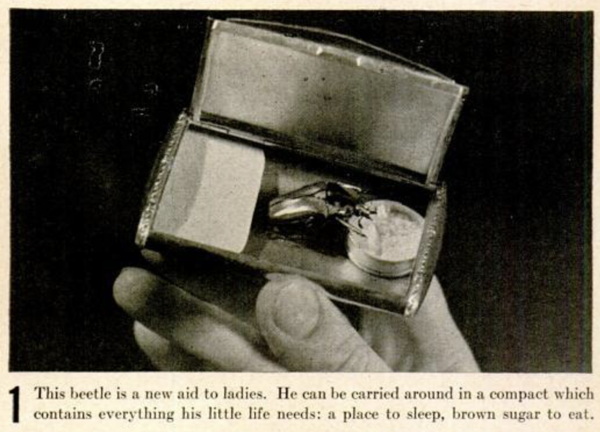

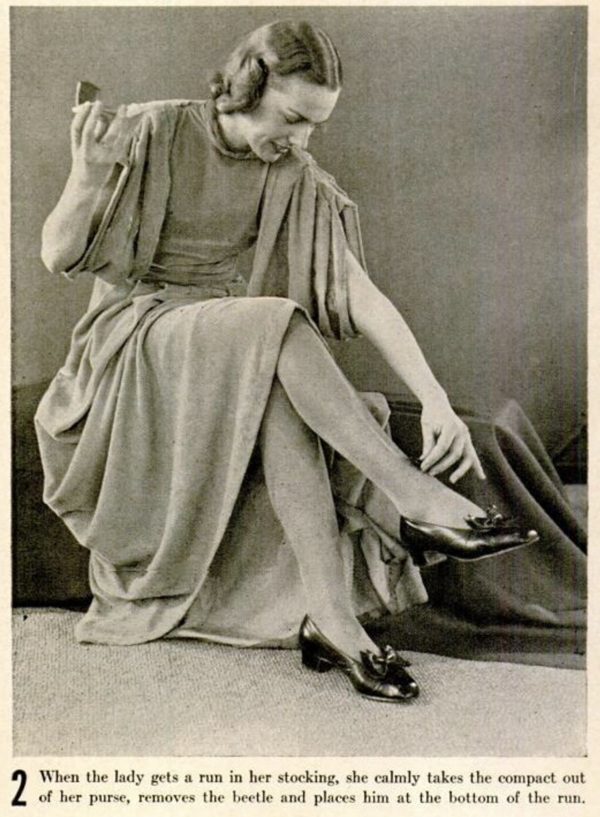

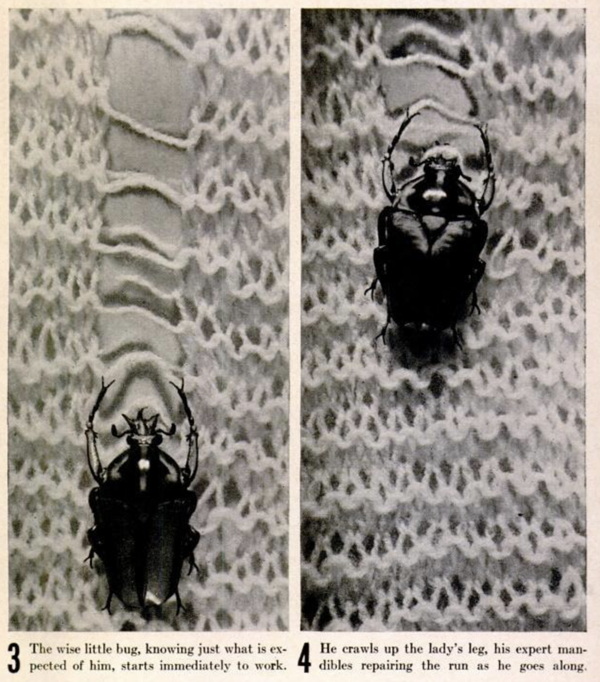

Stocking-Repairing Beetle

The "Aprilscherz" (April Fool) of an unnamed German magazine, as reported in Life (Apr 4, 1938):

Posted By: Alex - Mon Apr 01, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Holidays, Insects and Spiders, 1930s

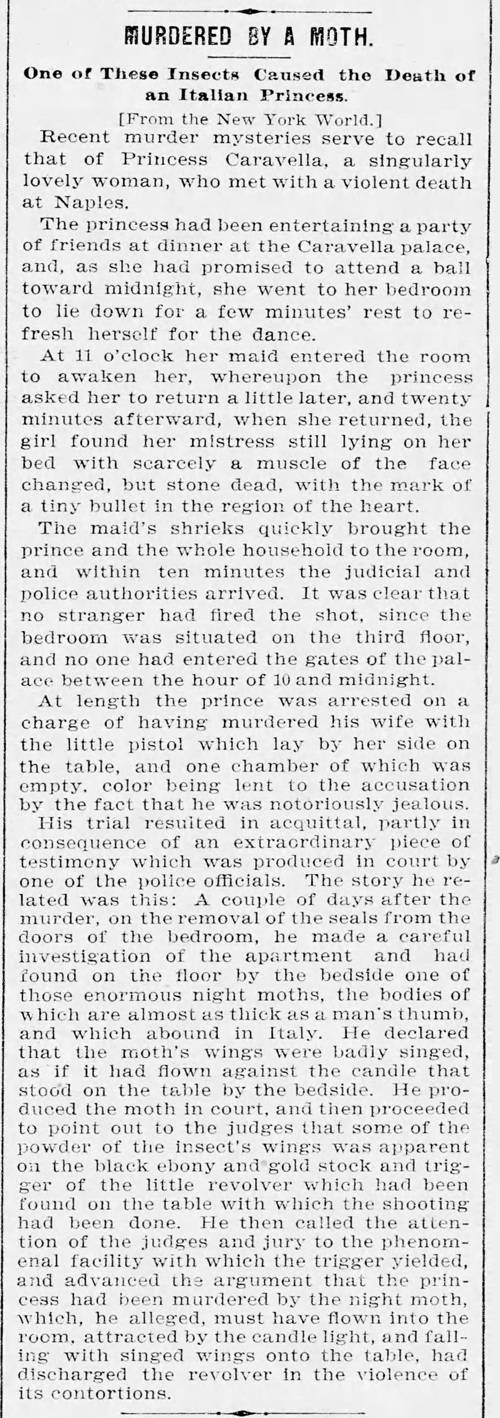

The Princess Who Was Murdered by a Moth

The story goes that Princess Caravella of Italy was found dead in her bed, shot through the heart. Her husband was accused of her murder, but during the trial a police investigator convinced the jury that the Princess had actually been killed by a moth that singed its wings on a candle in her room, then fell onto a pistol lying on her bedside table, thereby causing the weapon to fire, shooting her through the heart.I doubt any part of this story is true. After all, I can't find any historical references to a "Princess Caravella" other than the ones about her strange death. But the story was printed repeatedly in newspapers during the first half of the twentieth, always presented as an odd but true tale.

The earliest account of the story I can find dates to 1895, where it was credited to the New York World. I assume a reporter for the New York World made it up.

Chicago Chronicle - Dec 29, 1895

Here's a slightly shorter version of the story from 1937.

Tunkhannock New Age - Feb 18, 1937

I can't find the story in papers after the 1940s, but it did continue to pop up in books about odd trivia and weird deaths. For instance, below is a version that appeared in the 1985 weird-news book Own Goals by Graham Jones. Note that Jones identified Princess Caravella only as an "Italian wife," making the story seem more contemporary.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Mar 14, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, Insects and Spiders, Nineteenth Century

Anting

A strange behavior engaged in by birds. From wikipedia:

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jan 27, 2024 -

Comments (6)

Category: Animals, Insects and Spiders

Ill-Treating Prawns

We've previously posted about a British case involving cruelty to goldfish. Here the British courts took up the question of whether it's possible to be cruel to prawns (aka shrimp), but dropped the case when it decided that prawns were insects and so not covered by anti-cruelty laws. They're actually crustaceans, but close enough I guess.

Feb 28, 1974 - Minneapolis Star

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 25, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Insects and Spiders, Law, Sadism, Cruelty, Punishment, and Torture, United Kingdom

Hitler Species

There are two species of insects named after Hitler. The mystery, however, might be why more creatures weren't named after Hitler by German scientists during the 1930s, as a way to curry favor with him. The answer, surprisingly, seems to be that requests were made, but Hitler would always ask for his name not to be used. (The insect researchers never asked for his permission). Text from The Art of Naming by Michael Ohl (2018 translation):To date, Anophthalmus hitleri has been found in but a handful of caves in Slovenia. Particularly after the media discovered and circulated the Hitler beetle story in 2000, interest in this species has been rekindled. A well-preserved specimen of Anophthalmus hitleri can fetch upward of 2,000 euros on the collectors' market; among the bidders, certainly some wish to add the Hitler beetle to their collection of Nazi memorabilia. . .

At least one other species has been named after Adolf Hitler: the fossil Roechlingia hitleri, which belongs to the Palaeodictyoptera, a group of primitive fossil insects. Roechlingia hitleri was described in 1934 by German geologist and paleontologist Paul Guthörl. . .

Extensive research has failed to turn up any other species named in honor of Hitler. This seems surprising, as this form of salute could have proven quite expedient to aspiring German scientists from about 1933 until 1945, at the latest...

The likeliest explanation is that when Hitler patronyms were planned, approval was sought in advance from the Führer (by way of the Reich Chancellery), whether out of respect or perhaps fear of potential consequences. In 1933, for instance, a rose breeder submitted a written request to the Reich Chancellery for permission to introduce to the international market one of his best rose varieties, bearing Hitler's name. Similarly, a nursery owner from Schleswig-Holstein hoped to name a "prized strawberry variety" the "Hitler strawberry," in honor of the Reich Chancellor. They already had a "Hindenburg" strawberry variety in their catalog, he added. In reply to both cases, Hans Heinrich Lammers, Chief of the Reich Chancellery, sent almost identical letters, in which the inquiring parties were informed that, "upon careful consideration, [the reich Chancellor] requests that a name in his honor most kindly not be used." . . .

Perhaps this fundamental rejection of honorary names is the reason that so few hitleris exist.

Anophthalmus hitleri

source: Wikipedia

Posted By: Alex - Fri Sep 01, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Dictators, Tyrants and Other Harsh Rulers, Insects and Spiders, Odd Names, Science

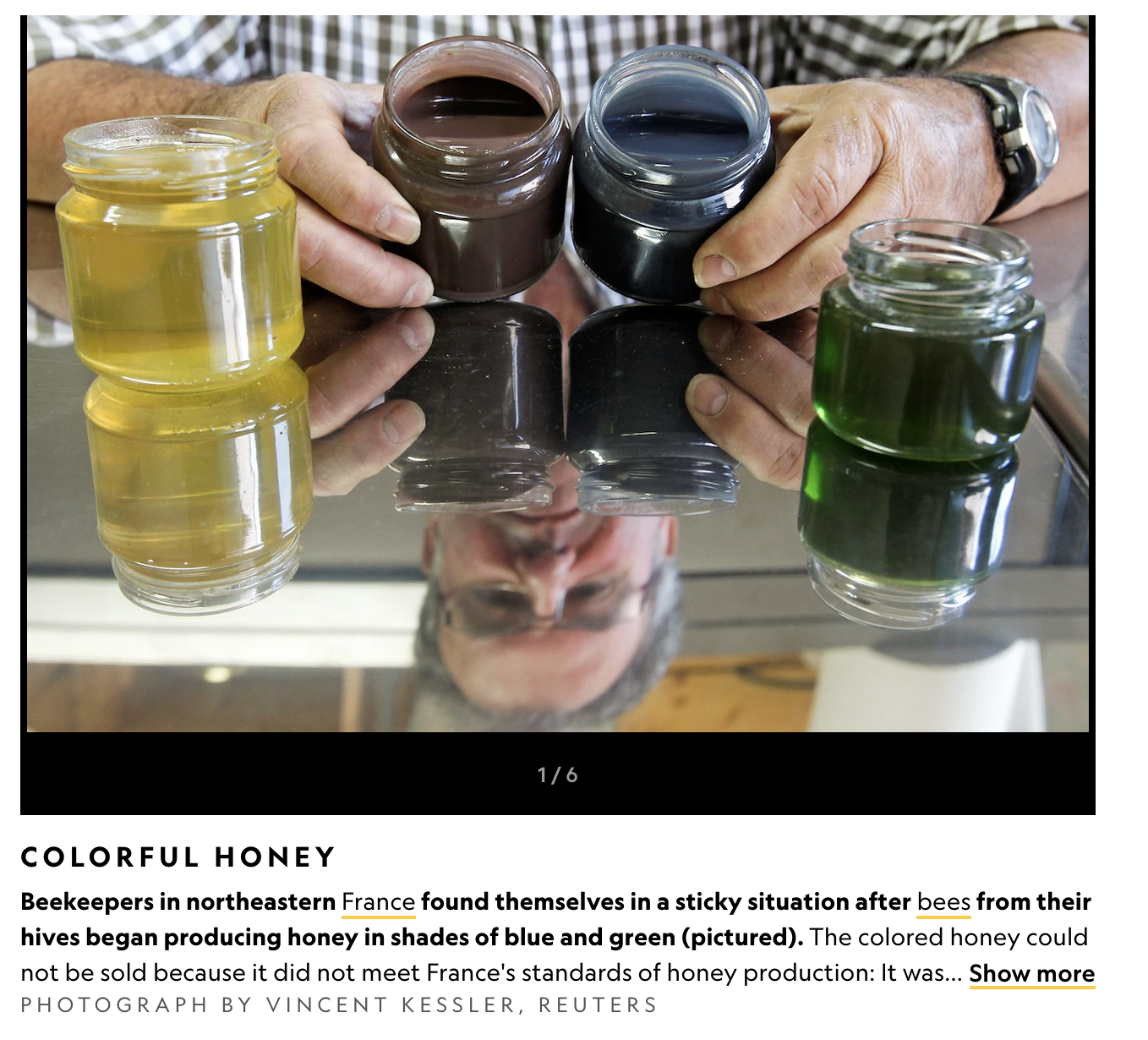

M&M Honey

I read this story upon its appearance, and for some reason it recently returned to the forefront of my mind. It seems that someone would have subsequently produced this intentionally.When I was in Sicily, I got to sample the light-green pistachio honey produced there.

NBC video report here.

Whole article and more pics here.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 20, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Insects and Spiders, Europe, Twenty-first Century

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |