Eighteenth Century

The type specimen of humanity

The Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences offers the following definition of a "type specimen":Biologists have amassed type specimens for hundreds of thousands of different species. But by the mid-twentieth century it had occurred to some of them that they were missing a type specimen for one very important species: Homo sapiens.

In 1959, the botanist William Stearn offered a solution to this problem: Make Carl Linnaeus, the founder of modern taxonomy, the type specimen for all of humanity.

Carl Linnaeus. (source: wikipedia)

The story is told by Jason Roberts in Every Living Thing (his new biography of Carl Linnaeus):

The methodology had relaxed somewhat in the first part of the twentieth century, with some scientists substituting instead a syntype, a listing of several examples of a species, none of which had priority over the other. But Stearn was writing in light of a recent crackdown. The keepers of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature had announced a return to Linnean orthodoxy: All new species would henceforth again be defined by a single instance only, called either a holotype (if chosen by the first describer of the species) or a lectotype (if chosen at a later date). Linnaeus's specimens became holotypes as soon as he used them in compiling Systema Naturae... Its specimens were the definitive examples- the embodiments, so to speak- of their respective species.

Yet Linnaeus had neglected to collect the type specimen of one important species. He had never supplied a holotype for Homo sapiens, and for that matter had defined the species only with the terse phrase nosce te ipsum, Latin for "know yourself." Stearn proposed a novel means of correcting this omission. Since "the specimen most carefully studied and recorded by the author is to be accepted as the type," he wrote, the appropriate lectotype was obvious. Linnaeus had presumably examined himself for decades, even if only by glancing in the mirror while shaving.

"Clearly," Stearn concluded, "Linnaeus himself. .. must stand as the type of his Homo sapiens!"

Seven years later the International Committee on Zoological Nomenclature adopted Stearn's suggestion and officially made the body of Linnaeus (entombed in Uppsala Cathedral) the type specimen for all of humanity.

The website Nutcracker Man has photographs of the type specimens for all the known hominim species. At the bottom of the list, next to Homo sapiens, is a portrait of Linnaeus.

More info: whyevolutionistrue.com

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 07, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Science, Eighteenth Century

The Spectrum of Intemperance

Where do you fall on the boozy scale?Source.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Mar 20, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Eighteenth Century

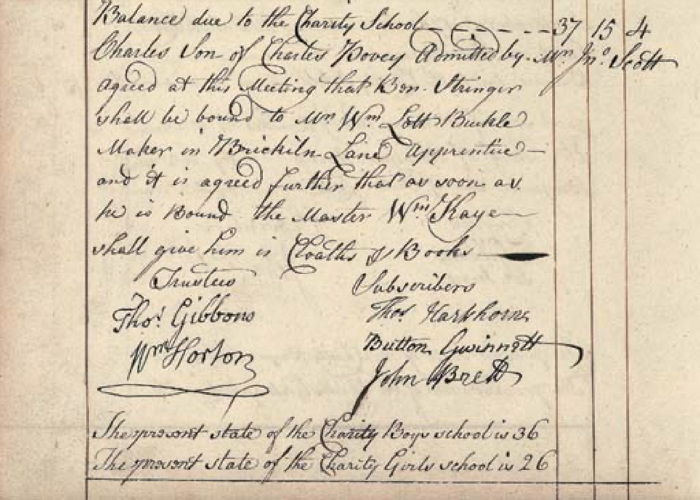

The Signature of Button Gwinnett

In the world of signature collecting the "holy grail" is to obtain a signature of Button Gwinnett, a representative from Georgia to the Continental Congress and also a signer of the Declaration of Independence. As explained by Wikipedia:In 2022, a copy sold for $1.4m.

If you're going to build a device to move objects through time, I think you can do better than that.

image source: Christies.com

Posted By: Alex - Mon Dec 18, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Collectors, Eighteenth Century

The Lion of Gripsholm Castle

In 1731, a lion was given as a gift to King Frederick I of Sweden. When it died it was sent to a taxidermist for preservation. Unfortunately, the taxidermist wasn't sure what a lion was supposed to look like, and this was the result:

More info: Design You Trust

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jul 24, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Taxidermy, Eighteenth Century

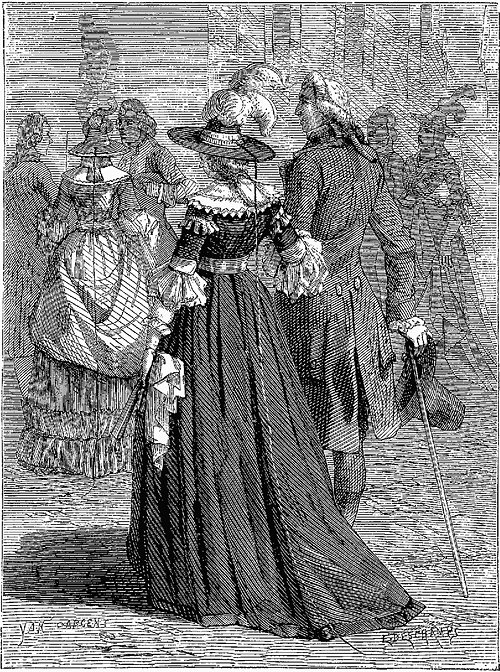

Lightning Rod Hat

AKA "Le chapeau paratonnerre." Details from Amelia Soth on JStor Daily:

image source: wikimedia

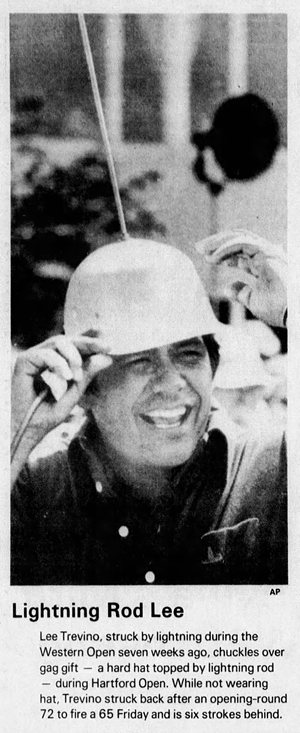

A more recent version of a lightning-rod hat:

Tampa Bay Times - Aug 16, 1975

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 21, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Headgear, Weather, Eighteenth Century

Mystery Gadget 101

What's it for?

The answer is here.

or after the jump.

More in extended >>

Posted By: Paul - Thu Apr 14, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Technology, Eighteenth Century

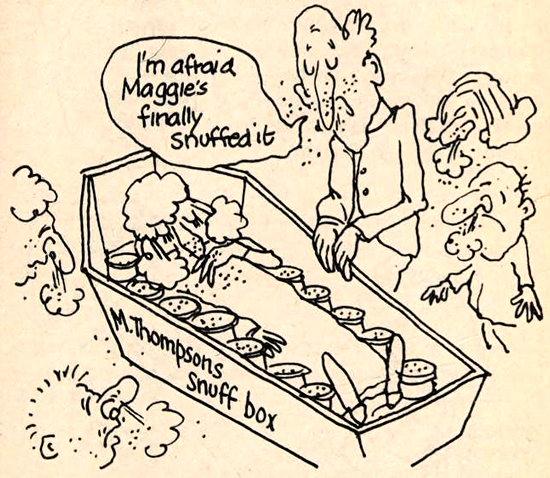

Buried in Snuff

Margaret Thompson of London was buried on April 2, 1776. Her will directed that her casket should be filled with snuff, and that snuff should be liberally handed out to the crowd at her funeral.I also desire that all my handkerchiefs that I may leave unwashed at the time of my disease, after they have been got together by my old and trust servant, Sarah Stuart, be put by her alone, at the bottom of my coffin, which I desire may be large enough for that purpose, together with such a quantity of the best Scotch snuff (in which she knoweth I always had the greatest delight) as will cover my deceased body — and this I desire more especially, as it is usual to put flowers into the coffin of departed friends, and nothing can be so fragrant and refreshing to me as that precious power.

But I strictly charge that no man be suffered to approach my body till the coffin is closed, and it is necessary to carry me to my burial, which I order in the manner following:

Six men to be my bearers, who are well known to be the greatest snuff takers in the parish of St. James', Westminster—and instead of mourning, each to wear a snuff coloured beaver, which I desire may be bought for that purpose, and given them.

Six maidens of my old acquaintance, viz. &c. to bear my pall, each to wear a proper hood, and to carry a box filled with the best Scotch snuff, to take for their refreshment as they go along. Before my corpse I desire the minister may be invited to walk, and to take a desirable quantity of the said snuff, not exceeding one pound; to whom I bequeath two guineas on condition of so doing. And I also desire my old and faithful servant, Sarah Stuart, to walk before the corpse, to distribute every twenty yards, a large handful of Scotch snuff to the ground, and upon the crowd who may possibly follow me to the burial place—on which condition I bequeath her £20. And I also desire, that at least two bushels of said snuff may be distributed at the door of my house in Boyle street.

Source: Euterpeiad, or, Musical Intelligencer & Ladies' Gazette - June 28, 1821

Source: Crazy - But True!, by Jonathan Clements

Posted By: Alex - Sat Mar 05, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Eighteenth Century

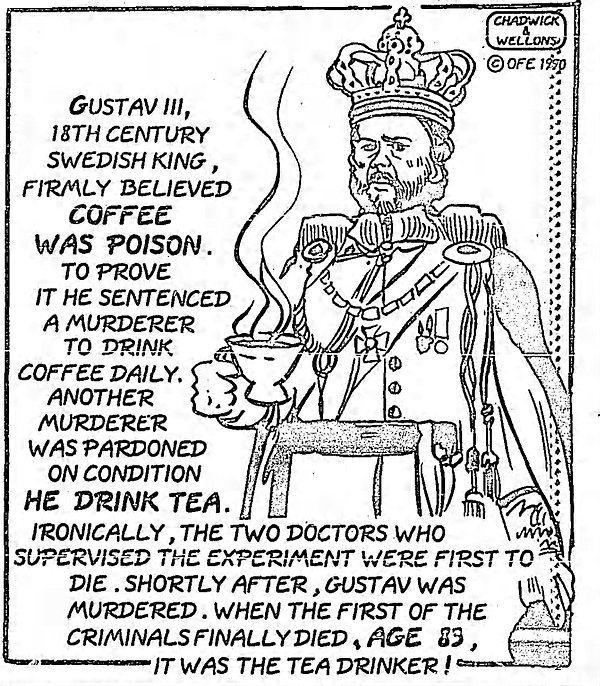

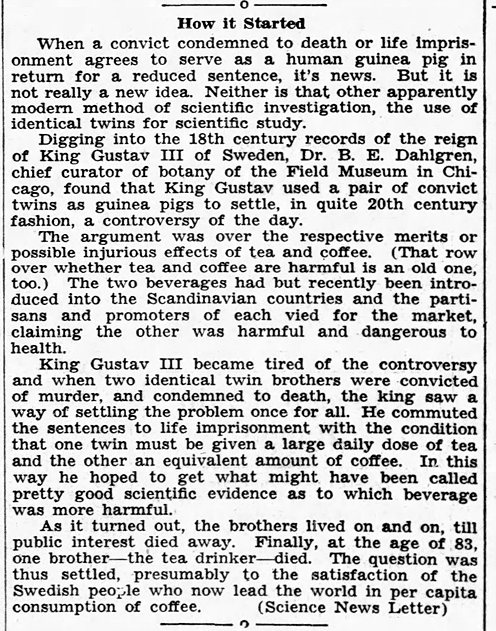

King Gustav III’s Coffee Experiment

According to what may be legend, King Gustav III of Sweden conducted that country's first clinical trial during the second half of the 18th century. He wanted to determine whether drinking coffee was bad for one's health. He firmly believed it was. The story is told on the website of Sweden's Uppsala University Library:

Barstow Desert Dispatch - Jan 7, 1991

Wikipedia notes that the authenticity of the coffee experiment story has been questioned. Though it doesn't say why.

As far as I can tell, the earliest English-language reference to the story appeared in a 1937 issue of The Science News-Letter. This account was then widely reprinted in newspapers (see below).

The Science News-Letter attributed the information to the Swedish-born botanist Bror Eric Dahlgren, who was a curator at the Field Museum in Chicago. Dahlgren did author a 1938 pamphlet about the history of coffee, which you can read online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library, but it doesn't include the story of King Gustav. I can't locate where else Dahlgren might have told the story of the coffee experiment, which makes it impossible to check his references.

The Sheboygan Press - May 28, 1938

Posted By: Alex - Thu Sep 23, 2021 -

Comments (5)

Category: Experiments, Coffee and other Legal Stimulants, Eighteenth Century

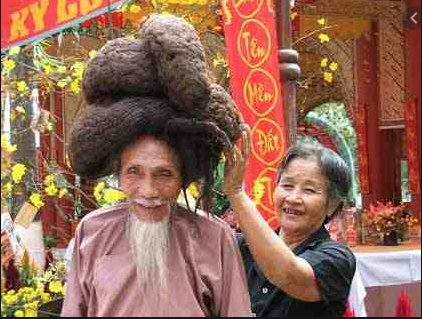

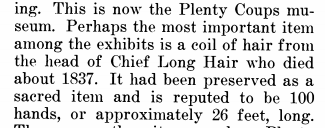

Chief Long Hair

The modern-day Vietnamese man named Tran Van Hay reputedly had hair "over 22 feet long."

Other modern record-holders are in the 18-ft range.

But they can't hold a patch to Chief Long Hair of the Crows.

Itchuuwaaóoshbishish/Red Plume (Feather) At The Temple (born ca. 1750, died in 1836) A Mountain Crow leader during fur trade days and signer of the 1825 Friendship Treaty. Traders and trappers called him Long Hair because of his extraordinarily long hair, approximately 25 feet long. At his death, his hair was cut off and maintained by Tribal leaders.

Now because Long Hair lived before photography, there is no visual record of this. However! Supposedly his tresses are part of the exhibit at Chief Plenty Coups State Park in Montana. (Plenty Coups was a descendant of Long Hair.)

Source of quote.

If any WU-vie is passing by the museum, perhaps he or she can confirm!

Here's a photo of another Crow tribe-member named "Curley."

Posted By: Paul - Thu Jul 30, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Human Marvels, World Records, Eighteenth Century, Nineteenth Century, Hair and Hairstyling, Native Americans

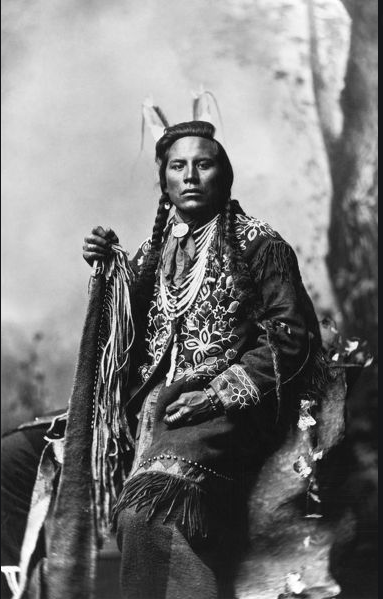

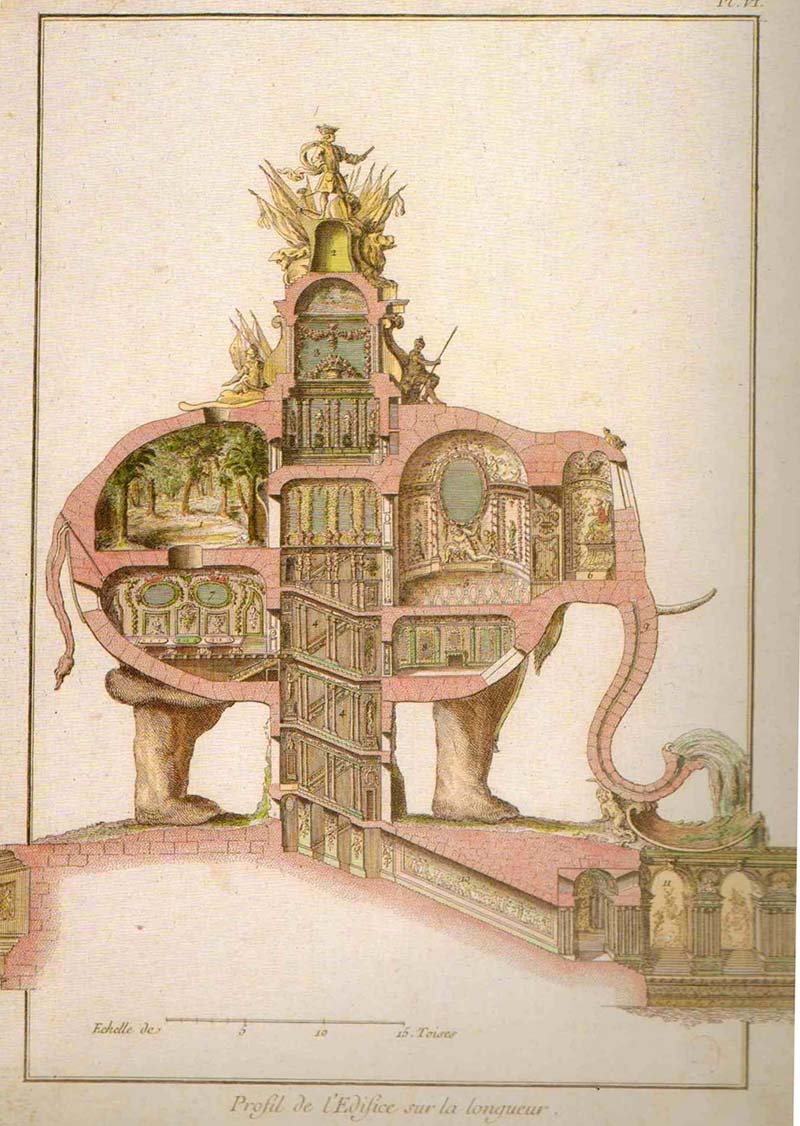

Jean-Jacques Lequeu, Visionary Architect

Lots of bizarre stuff from this creator, seen at this page, and also here.And if you're in New York City over the next couple of months, you can visit an exhibit.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Feb 05, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Art, Eccentrics, Eighteenth Century, Nineteenth Century

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |