Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore

An inglorious Columbus : or, Evidence that Hwui Shn and a party of Buddhist monks from Afghanistan discovered America in the fifth century, A.D

Why waste your red paint and enmity on statues of Columbus, when it was really the Chinese who discovered America?Read it here.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Jun 30, 2024 -

Comments (4)

Category: Explorers, Frontiersmen, and Conquerors, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, Asia, North America, Nineteenth Century

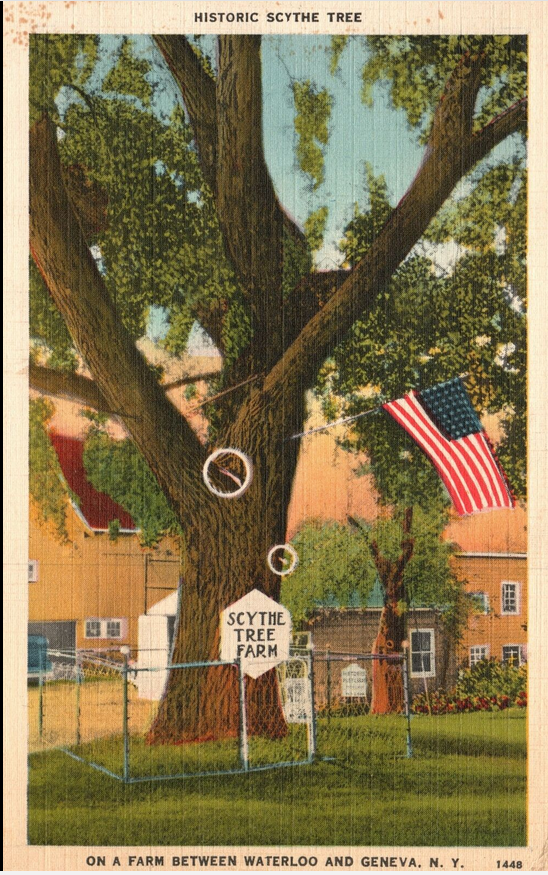

The Scythe Tree

Atlas Obscura article.Roadside America article.

Local newspaper article.

James Wyman Johnson attended a Union army recruitment meeting at the Vail country schoolhouse in October 1861, about five months after the start of the Civil War. As he was mowing with his scythe the next morning, he decided to enlist. When he returned to the house, he hung his scythe in the small tree, about 8 inches in diameter and just a few feet tall, near the kitchen door. He told his parents he was going to enlist and remarked that the scythe was to stay hanging on the tree until he returned from war.... He died on May 22, 1864, from his wounds and was buried in an unknown grave.... Years passed and the handle fell away, the tree grew and gradually surrounded the blade. The long scythe blade only protruded a few inches outside the mammoth tree trunk.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Nov 03, 2023 -

Comments (2)

Category: Agriculture, Death, Family, War, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, Nineteenth Century

The Unspeakable sin of Charlemagne

After the death of Charlemagne (in 814 AD), a legend emerged alleging that the ruler had committed some kind of "unspeakable sin."The legend first appeared in print in a 10th-century work called The Life of St. Giles. According to this work, Charlemagne had sought out St. Giles to ask the saint to pray for him because he had committed a sin so terrible that he had never been able to confess it properly. Giles reportedly agreed to pray for the king, even though Charlemagne didn't tell him what the sin was.

The fact that the unspeakable sin wasn't disclosed whet the imaginations of later medieval writers, creating a minor genre devoted to exploring what the sin was. Details from Charlemagne: Father of Europe (2022) by Philip Daileader.

The allegation of an incestuous relationship between Charlemagne and Gisela appears in the Karlamagnus Saga, a 13th century account of Charlemagne's life written in Norse. From there, the incest claim is then taken up by a number of different texts, especially French texts.

Other authors identified Charlemagne's unspeakable sin as necrophilia. That claim appears in a 14th century German poem about Charlemagne, "Karl Meinet," and the idea was then taken up in a number of 14th and 15th century German chronicles and treatises.

Specifically, someone had hexed Charlemagne by placing a charmed ring under the tongue of his dead wife. The ring caused Charlemagne to become infatuated with the wife and to continue the relations they had had while she was alive. When a bishop discovered the ring and removed it from the dead wife's mouth, Charlemagne became infatuated with the bishop. The bishop tossed the ring into a swamp, and Charlemagne became infatuated with the swamp, building a palace and dwelling there. To be clear, none of this is true...

One can only speculate as to why stories arose alleging that Charlemagne was guilty of incest or necrophilia, and why those stories gained a significant and distinguished audience. These stories did not emerge in or remain confined to a specific geographical milieu. They do not seem to have been concocted to achieve any specific political outcome. Perhaps they emerged primarily as a reaction against the overblown praise that Charlemagne received in other works. The bigger they come, the harder they fall.

Detail from a Flemish altarpiece (ca. 1400) showing Charlemagne asking St. Giles to pray for him.

Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Posted By: Alex - Fri Sep 29, 2023 -

Comments (3)

Category: Medieval Era, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore

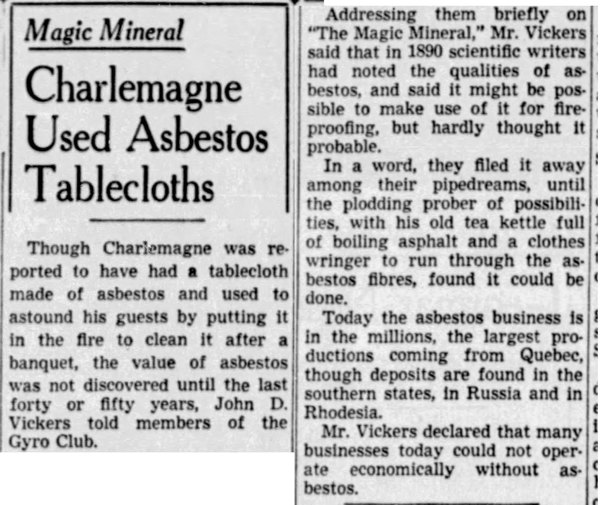

Charlemagne’s asbestos tablecloth

Legend has it that Charlemagne owned an asbestos tablecloth. This allowed him to perform an unusual party trick. After hosting a feast, he would entertain his guests by throwing the tablecloth in the fire. All the food and stains would burn off, but the cloth itself didn't burn. When removed the fire it was not only undamaged but also sparkling clean.The story can be found in a lot of sources, such as in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1911), in the article about asbestos. Or in the newspaper article below.

Vancouver Daily Province - Mar 27, 1940

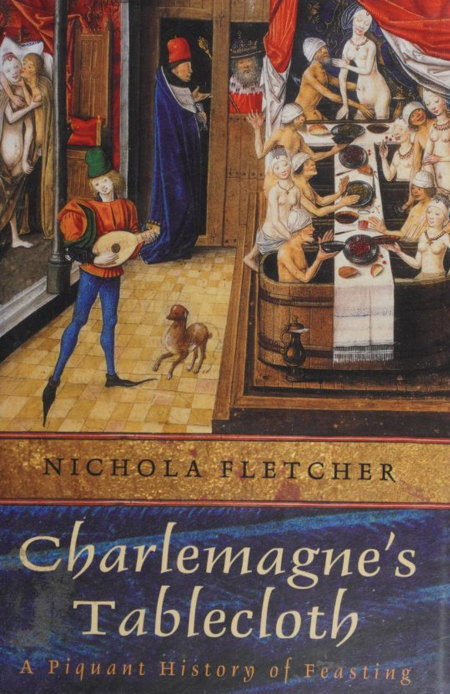

But is there any truth to the legend? The best answer to this question I could find is in the book Charlemagne's Tablecloth (2004) by Nichola Fletcher. Most of the book isn't actually about Charlemagne (it's about the history of feasting), but in the afterword she looks specifically at the legend.

She notes that the ancient Greeks and Romans had created cloth out of asbestos. Pliny the Elder wrote about the existence of asbestos napkins. So it's possible that Charlemagne had an entire tablecloth made from the material. However, she was unable to find any reference to the story in medieval sources about Charlemagne. Frustrated, she eventually requested help from Donald Bullough, an expert on Charlemagne who taught at St. Andrews University. This was Bullough's reply:

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 14, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Medieval Era, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore

Killer Candy

Read the thrilling urban legend here.

Posted By: Paul - Sat May 27, 2023 -

Comments (7)

Category: Death, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, Advertising, Candy, 1970s

The Handsome Cabin Boy

Surely such a filthy song should incite the outrage of censors!BONUS: Versions by Kate Bush and Jerry Garcia in extended.

In the 19th century, broadside texts of the Handsome Cabin Boy remained steady sellers on the fairgrounds and in the backstreets of provincial towns for sixty years and more. A very widespread song, ashore as well as afloat, it is still not infrequently found among traditional singers in eastern England and north-eastern Scotland.

It's of a pretty female as you may understand

Her mind being bent for ramblin' all unto some foreign land

She dressed herself in sailor's clothes or so it does appear

And she hired with a captain to serve him for a year

The captain's wife, she being on board, she seemed in great joy

To think her husband had engaged such a handsome cabin boy

And now and then she'd slip him a kiss, and she would 'a liked to toy

It was the captain found out the secret of the handsome cabin boy

Her lips they were like roses, her hair allwas all in a curl

The sailors often smiled and said, "she looks just like a girl"

But eating of the captain's biscuit, her color did destroy

And the waist did swell of pretty Nell, the handsome cabin boy

It was in the Bay of Biscayne, our gallant ship did plough

One night among the sailors was a fearful flurry and row

They tumbled from their hammocks, for sleep it did destroy

They swore about the groaning of the handsome cabin boy

"Oh doctor, dear, oh doctor", the cabin boy did cry

"My time has come, I am undone, surely I must die"

The doctor cam a-runnin', and smilin' at the fun

To think a sailor lad should have a daughter or a son

The sailors, when they saw the joke, they all did stand and stare

The child belonged to none of them, they solemnly did swear

The captain's wife she says to him "My dear I wish you joy

For it's either you or me's betrayed the handsome cabin boy"

So each man took his tote of rum, and he drunk success to trade

And likewise to the cabin boy, who was neither man nor maid

"Here's hoping wars don't rise again, our sailors to destroy

And here's hoping for a jolly lot more like the handsome cabin boy"

More in extended >>

Posted By: Paul - Tue Dec 06, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Disguises, Impersonations, Mimics and Forgeries, Music, Oceans and Maritime Pursuits, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, Pregnancy

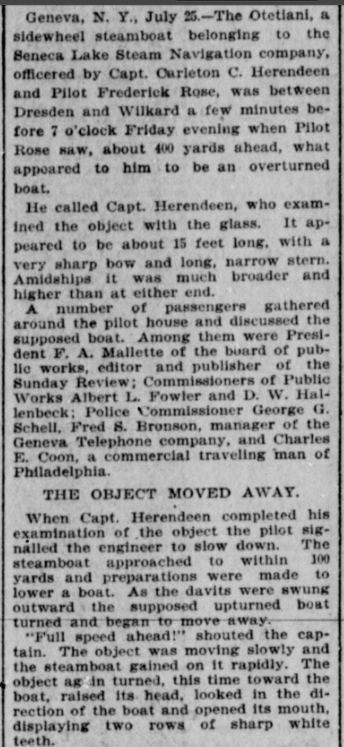

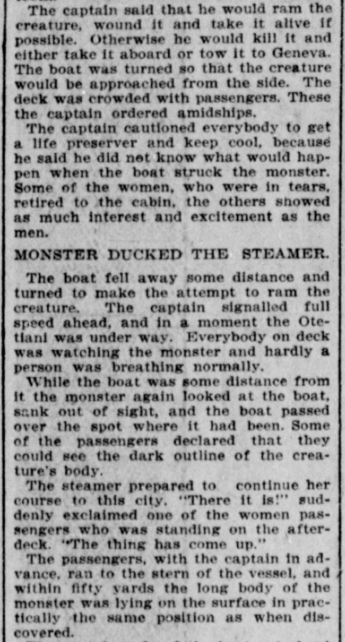

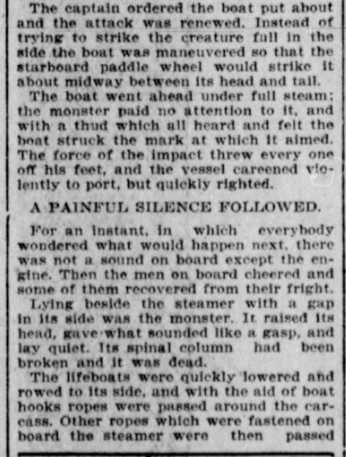

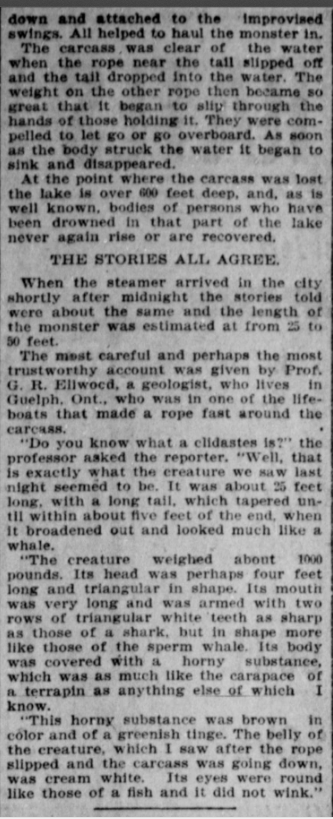

The Seneca Lake Monster

One of the lesser-known giant enigmas to haunt the lakes of the Northeast USA.Source of article below.

Posted By: Paul - Sun May 15, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Cryptozoology, Regionalism, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, North America

Death by Drama

Paul posted last week about a real-life murder that occurred onstage during a play. This reminded me of another onstage death I once read about in Jody Enders' book Death By Drama and Other Medieval Urban Legends.The death is said to have occurred in 1549, during a performance of the play Judith and Holofernes, which tells the Biblical (or Biblical apocrypha) story of Judith who cuts off the head of an Assyrian general, Holofernes. The producers of the play supposedly decided it would add a touch of realism if the actor playing Holofernes really was decapitated.

The details from Enders' book:

Jean de Bury and Jean de Crehan, duly charged with decorating the streets, had imagined rendering in its purest form the biblical exploit of Judith. Consequently, for filling the role of Holofernes, a criminal had been chosen who had been condemned to have his flesh torn with red-hot pincers. This poor fellow, guilty of several murders and ensconced in heresy, had preferred decapitation to the horrible torture to which he had been condemned, hoping, perhaps, that a young girl would have neither the force nor the courage to cut off his head. But the organizers, having had the same concern, had substituted for the real Judith a young man who had been condemned to banishment and to whom a pardon was promised if he played his role well.

The story goes that the two substitutions were accepted by the two unnamed men. Being an actor / executioner was apparently preferable to being banished, and death by decapitation during drama was preferable to being skinned alive (something that the Eel of Melun might himself have understood).

"Judith" had only one condition to meet: to provide acting so good that it wasn't acting at all. . .

The fantastic narrative next shows Philip arriving just as the axe is falling. As real blood supposedly begins to flow, it prompts applause in some, indignation in others, and curiosity in the prince, who remains implacable as the body of "Holofernes" goes through its last spasms:

In fact, as Philip approached the theater where the mystery play was being represented, the so-called Judith unsheathed a well-sharpened scimitar and, seizing the hair of Holofernes, who was pretending to be asleep, dealt him a single blow with so much skill and vigor that his head was separated from his body. At the [sight of] the streams of blood that spurted out from the neck of the victim, frenetic applause and cries of indignation rose up from amid the spectators. Only the young prince remained impassive, observing the convulsions of the decapitated man with curiosity and saying to his noble entourage: "nice blow".

Enders has doubts this onstage execution ever really took place, but can't rule out the possibility altogether.

In the story's favor: Philip II really did go to Tournai in 1549; Jehan de Crehan was a real person; there really were plays performed in Philip's honor; and Tournai had a history of executing heretics, and of offering decapitation as a "kinder" alternative to more gruesome forms of execution.

The points against the story's veracity: not a single, extant contemporaneous source mentions this onstage decapitation. The first references to it only appear several hundred years later. And it stretches credulity to imagine that a condemned prisoner would obligingly play his part in the performance, even to the extent of pretending to be asleep before he was decapitated.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 18, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Death, Theater and Stage, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, Sixteenth Century

Formaldehyde Hunger

According to medical student lore, the smell of formaldehyde while dissecting bodies stimulates the appetite. This phenomenon is known as 'formaldehyde hunger'.It was mentioned in a 2020 article by Amalia Namath in the Georgetown Medical Review, and that's the earliest reference to it I've been able to find:

An article on mashed.com disputes the reality of the phenomenon, noting, "there is some self-reported evidence of formaldehyde actually having the opposite effect — constricting hunger, rather than inducing it."

My guess is that med students just naturally build up an appetite during the long hours they're dissecting a cadaver. After all, they're presumably not snacking while they're doing this. The formaldehyde has nothing to do with their hunger. But it makes a better story to attribute their food cravings to the formaldehyde.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jan 09, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Food, Science, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore

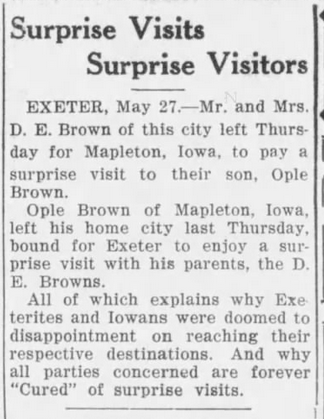

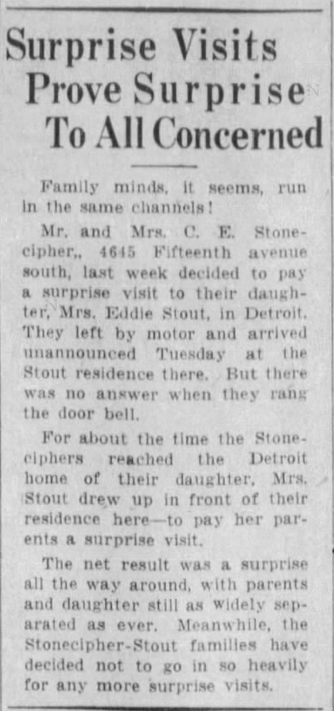

Surprise, Surprise!

Did this really happen twice in the space of a year, in a manner that became noticeable to a newspaper? Or was it the invention of a bored and desperate reporter, then copied by another?Source for first item: Lindsay Gazette (Lindsay, California) 31 May 1935, Fri Page 11

Source for second item: Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg, Florida) 29 May 1936, Fri Page 2

Posted By: Paul - Thu Dec 02, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Domestic, Travel, Fables, Myths, Urban Legends, Rumors, Water-Cooler Lore, 1930s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |