Books

100 Photos That Aren’t Horse Photos

The title of Claude Closky's 1995 book, 100 Photos Qui Ne Sont Pas De Photos De Chevaux (100 Photos That Aren't Horse Photos), is totally accurate. His book consists of 100 photos of chickens.You can view all the photos on his website.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Aug 04, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Animals, Photography and Photographers, Books

Don’t Fool with Fu Manchu

The group's Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Aug 03, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Mad Scientists, Evil Geniuses, Insane Villains, Music, Stereotypes and Cliches, Books, 1960s, Asia

Jim’s Guide to San Francisco

In 1977, artist James Patrick Finnegan published an oddball guide to San Francisco, titled Jim's Guide to San Francisco. It consisted of pictures of him posing in front of San Francisco businesses that were named Jim: Jim's Barber Shop, Jim's Donut Shop, Jim's Transportation, Jim's Smoke Shop, etc.The book was printed in black-and-white, but he handcolored parts of it with a crayon. I assume he individually handcolored each copy sold.

I haven't been able to find any scanned copies of the book online, and only one copy of it for sale. The seller is asking $300, justifying that price by the book's rarity.

It's been almost 50 years since the book came out, so Finnegan should do an updated guide. I'm sure there's now a whole new batch of businesses in the city named Jim.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 28, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Books, Tourists and Tourism, 1970s

Soviet Bus Stops

Canadian photographer Christopher Herwig has been on a mission to raise awareness of Soviet bus stops. He feels that they're an under-appreciated form of architectural art, "built as quiet acts of creativity against overwhelming state control." But he warns that they're disappearing fast due to demolition.He collected together over 150 of his photographs in the 2015 book Soviet Bus Stops. More recently, a documentary film, again titled Soviet Bus Stops, follows his years-long effort to photograph the bus stops.

More info: Soviet Bus Stops

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jun 14, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Architecture, Mass Transit, Books, Documentaries, Bus

Patience Worth

Pearl Lenore Curran wrote four novels and many poems, but claimed that they had all been dictated to her by a woman named Patience Worth who had lived over two hundred years earlier. So, A body of work that was literally ghost-written.Info from Superstition and the Press (1983) by Curtis MacDougall:

Note: the Patience Worth poems were included in Braithwaite's 1918 anthology, not the 1917 one.

More info: Wikipedia, Smithsonian magazine

You can also find the Patience Worth novels on archive.org.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jun 12, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Literature, Books, Poetry, Paranormal

Don’t sit on your kids

I have a feeling that the author didn't intend for the title to sound funny.

Pittsburgh Press - Jan 18, 1985

Posted By: Alex - Thu May 23, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Children, Parents, Books

How many books do college students read?

We previously met Suellen Robinson as Miss Biological Research. Here she's posing by a stack of books that represents the number of books an average coed supposedly would read (back in the 1960s) during her four years at college. The number is 376.Officials of the Renault car company somehow arrived at this figure when they decided to sponsor a National College Queen Contest.

To read that many books a student would need to finish two books a week during the school year, and a book a week during Summer break.

I'm skeptical that the average college student (either back in the 1960s or now) reads anywhere close to that number. Perhaps they're assigned that many (though even that seems a bit high), but they're not reading them.

Orlando Evening Star - Apr 29, 1964

Posted By: Alex - Sun May 19, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Education, Universities, Colleges, Private Schools and Academia, Books, 1960s

Gilbert Young, most rejected author ever

Gilbert Young first came to the attention of the British press in the 1960s as a crusader for a single world government. He ran repeatedly for various political offices but never won an election.Below is an ad he placed in the papers seeking new members for his "World Government Party."

Bristol Daily Press - Jan 29, 1964

But his real claim to fame came in the mid 1970s when the editors of the Guinness Book of Records learned that, for years, Young had been trying to get his book published but had only received rejections from publishers. His book, World Government Crusade, had, by 1974, been rejected 80 times. So Guinness listed him in its 1975 edition as the record holder for the "greatest recorded number of publisher's rejections for a manuscript."

Bristol Daily Press - Sep 26, 1974

Guinness Book of Records 1975

For over fifteen years Guinness continued to list him as the holder of this record. Every few years it would update the number of his rejections. By 1990 his book had been rejected 242 times.

Guinness Book of Records 1991

I thought that perhaps Young's book would now be available to read or purchase somewhere on the Internet. But no, as far as I can tell it's still unavailable.

Posted By: Alex - Tue May 14, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Eccentrics, Politics, World Records, Books

Making Pigeons Pay

Wendell Levi's book is about how to make make money raising pigeons. Not about getting revenge on them. Though the latter would doubtless be a more interesting book.You can read the entire book for free at the Internet Archive.

Browsing through his book, I learned that squab is the term for pigeon meat. (I'm sure most WU readers knew this already, but it was news to me). I've never eaten squab. Nor can I recall ever seeing it for sale in a supermarket, or on a restaurant menu. But it's readily available online, such as at squab.com.

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 06, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Food, Farming, Books

Anne Carroll Moore and her Doll Nicholas

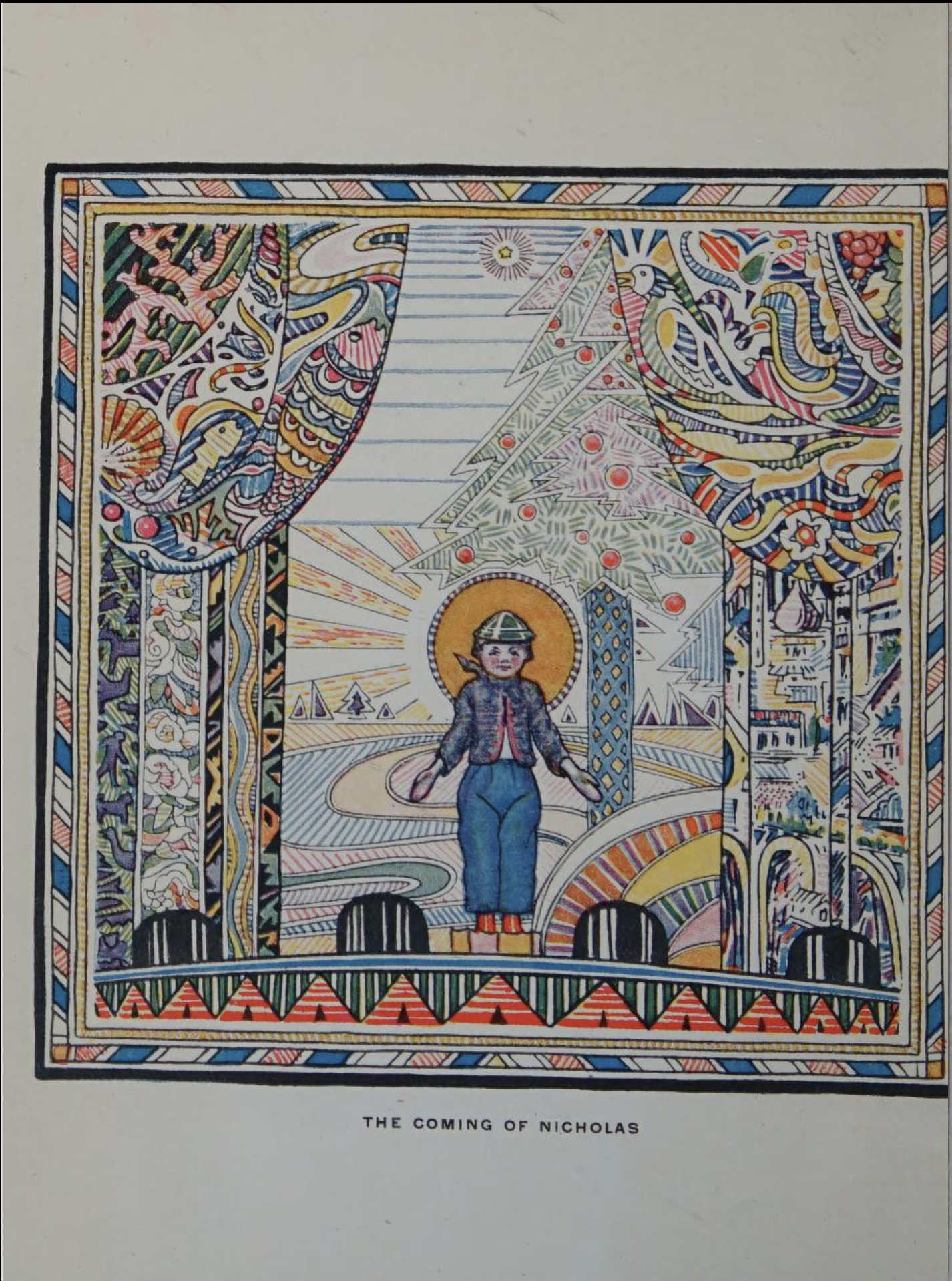

The famous children's librarian Anne Carroll Moore was wont to tote around a doll named Nicholas and make people interact with it.

She eventually wrote a whole book (300+ pages) about Nicholas: Nicholas: A Manhattan Christmas Story.

You can read the book here.

I have tried in vain to find a real photo of Nicholas. However, here is his depiction from the book.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Mar 05, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Books, Libraries, 1920s, Dolls and Stuffed Animals, Mental Health and Insanity

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |