Utopias and Dystopias

Laboratory Land

At a 1932 meeting of the British Association, scientist Miles Walker proposed the creation of a colony, initially to consist of 100,000 people, that would be entirely "under the auspices of engineers, scientists and economists." He suggested that it might be located somewhere in North America, or perhaps France. And he figured that the colony would be so successful that it could eventually be expanded to include the entire world.Walker didn't offer a name for his new colony, but the media dubbed it "Laboratory Land." More details from New Scientist (Aug 25, 1983):

Santa Cruz Evening News - Apr 1, 1933 (click to enlarge)

The key to the success of the colony, he believed, would be its efficiency and elimination of waste. Interestingly, one of the things he had in mind that would allow this efficiency was electric cars:

Almost 100 years later, and we're slowly working our way toward Walker's vision. At least, we are here in California where, by 2035, all new cars will have to be emission-free.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Oct 20, 2020 -

Comments (6)

Category: Utopias and Dystopias, 1930s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

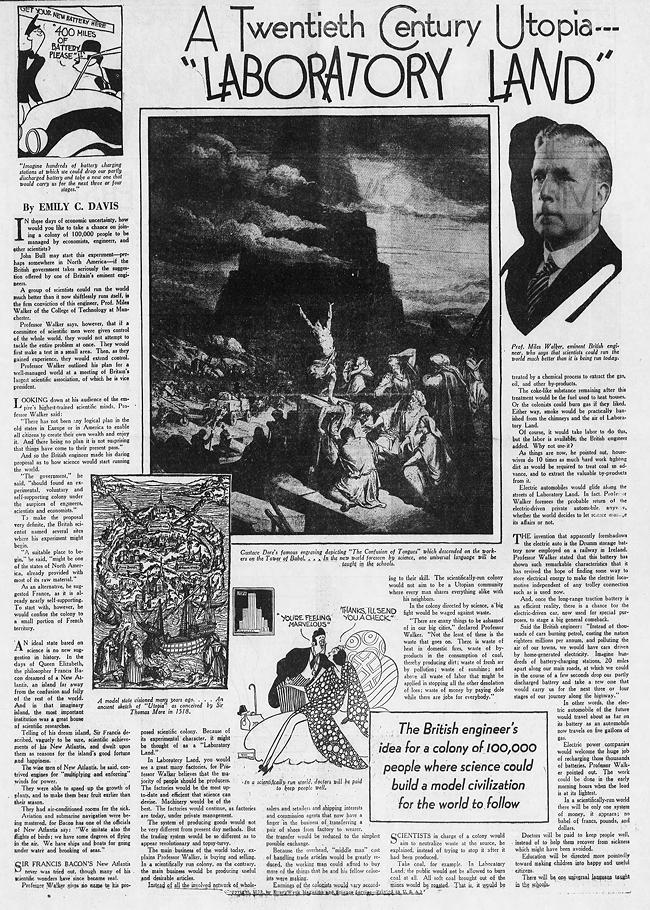

The Right To Be Lazy

Happy Labor Day!What better way to spend this annual celebration of work than by reading Paul Lafargue's 1883 treatise The Right To Be Lazy, in which he made a case for the virtues of idleness.

Some info about Lafargue and The Right To Be Lazy from RightNow.org:

Much of the book consists of a contrast between ideas about work in Lafargue’s day and the very different attitudes held in earlier societies, particularly in classical antiquity. Ancient Greek philosophers regarded work as an activity fit only for slaves. So where others hailed the arrival of modern industry as progress, Lafargue saw regression.

Longtime WU readers might remember that we've posted about Lafargue before. He made headlines back in 1911 for his unique retirement plan, which consisted of divvying up all he had for ten years of good living and then killing himself when the money ran out.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Sep 07, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Jobs and Occupations, Utopias and Dystopias, Books, Nineteenth Century

Charley in New Town

Once upon a time, the suburbs were going to be utopia.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Aug 21, 2013 -

Comments (7)

Category: Domestic, Dreams and Nightmares, Government, Urban Life, Utopias and Dystopias, 1940s, Europe

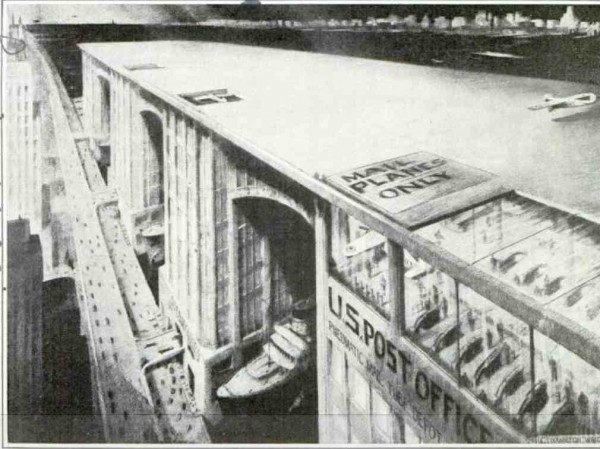

Manhattan Super Terminal

If only this gargantuan structure had actually been built! What a different world we would have inhabited....

Original article here.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jun 04, 2013 -

Comments (6)

Category: Engineering and Construction, Urban Life, Utopias and Dystopias, Transportation, 1930s

Los Angeles 100,000 years in the future

A headline in the Los Angeles Times, Apr 15, 1923. The author of the article, Ransome Sutton, elaborated:

So much concerning the inhabitants of Los Angeles in the year 101,923 AD.

Within the memory of old men, Los Angeles has grown into a city of some 700,000 inhabitants. Barring earthquakes, glaciers, acts of God and the public enemy, it should continue to grow, at an increasing rate, so long as mouths can be fed and the inhabitants housed. For it affords attractions of everlasting value — summery sunshine, health, rare air, good soil, scenery, the mountains in the background and in front the sea. Railroads extending to the eastward like a fan, and ocean routes radiating to the westward. Here, more surely than almost anywhere, continuous growth is insured.

Of course, he failed to foresee how bizarre many of the residents of Los Angeles would have become a mere 90 years later, let alone 100,000 years in the future!

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 24, 2013 -

Comments (11)

Category: Utopias and Dystopias, 1920s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

Predictions for 2013, made in 1913

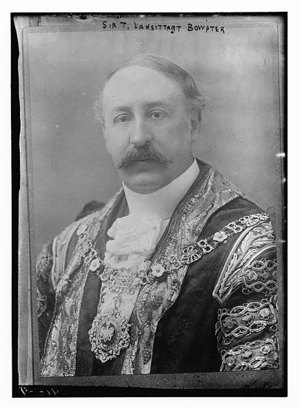

Sir Vansittart Bowater, predictor of the future

Back in 1913, Sir Vansittart Bowater, London's new lord mayor, made some predictions for how the world would look like in 2013 [Evening Independent, Dec. 6, 1913]. Now that 2013 has arrived, we can judge how accurate he was:

— a horse will excite far more wonder and curiosity in the city than an aeroplane or a dirigible flying over St. Paul's does today

Correct!

— the drone of great airships, each carrying perhaps many hundreds of passengers, will also probably be heard across both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans

Correct!

— these new aircraft will require "the protection of pedestrians and householders, possibly by wire netting laid over the housetops and even over the streets."

I'm not sure if he was foreseeing chunks of frozen poop falling from planes (blue ice). If so, his powers of prediction were impressive. But as for the netting, he was incorrect.

— the channel tunnel scheme may be a commonplace of actuality, with train services running every few minutes direct from London to Paris

The trains don't run every few minutes, but he got the general idea right, so I'll give him this.

— London will assuredly find part relief from the congestion between now and 2013 by the extension of her suburbs

Correct!

— postmarks and stamps may exist only as curiosities

Stamps are gradually on the way out, but they're not gone yet. So I'm judging him incorrect on this.

— a visit to Mars or the moon [may] be practicable in 2013... by harnessing the elusive ether, by electricity, or by some other at present unknown force capable of off-setting gravitation.

Correct! It was actually in 1914, one year after Bowater made his predictions, that Robert Goddard filed his first patent for a liquid-fuel rocket that would make spaceflight possible.

— such awful scourges as cancer and the hidden plague will be as much a memory as plague and the 'black death' are to us today

Not sure what he meant by the 'hidden plague,' but as far as cancer goes, he was unfortunately incorrect.

— he certainly will be a bold man in that year who will venture to say a person is dead beyond hope of resuscitation.

No. Dead is still dead.

Overall he scored 5 out of 9. Not bad. Better than most 100-year forecasts.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 01, 2013 -

Comments (11)

Category: Utopias and Dystopias, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |