Libraries

Episode in a small town library

Ian Breakwell's unusual photograph documents an "episode" that took place in an unnamed small town library in 1970. The episode seems to be a library user somehow transforming into, or sprouting, printed pages.

"Episode in a small town library" - Ian Breakwell, 1970

The only background information about the photograph that I've been able to find comes from Clare Qualmann's article "The Artist in the Library":

More detailed research into Breakwell's extensive archive held at Tate Britain did not provide answers in written form. Several versions of the image were published in journals, including Fotovision (August 1971), Art and Artists (February 1971) and Stand Magazine (Winter 1997). The different paper stocks that they were printed on enable more detail to be seen than the digital version that I had looked at before – in Art and Artists the photograph was reproduced on a newsprint insert to the magazine that is very different from the glossy black and white of the others. In this version, the chicken-wire frame underneath the newspaper is more visible, as are the titles on the bookshelf behind – Art and Civilization is clearly legible.

The version published in Fotovision has a completely different feel – instead of The Guardian newspaper on the table the artist holds a copy of Typographica magazine in his hands. Although this dates from 1964 (the photograph was taken in 1970), its cover design (an assemblage of logos arranged in a dense slanting pattern across the cover) juxtaposes old and new – the 'timeless' look of the traditional library space with the contemporary graphic design of the journal, and the branding that it is presenting. The existence of multiple versions suggests time spent in the space – time to shoot multiple images, test and trial different ideas and perform the image repeatedly (rather than a hit-and-runundercover-quick-photo-before-anyone-notices).

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jul 09, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Photography and Photographers, Performance Art, Surrealism, Libraries, 1970s

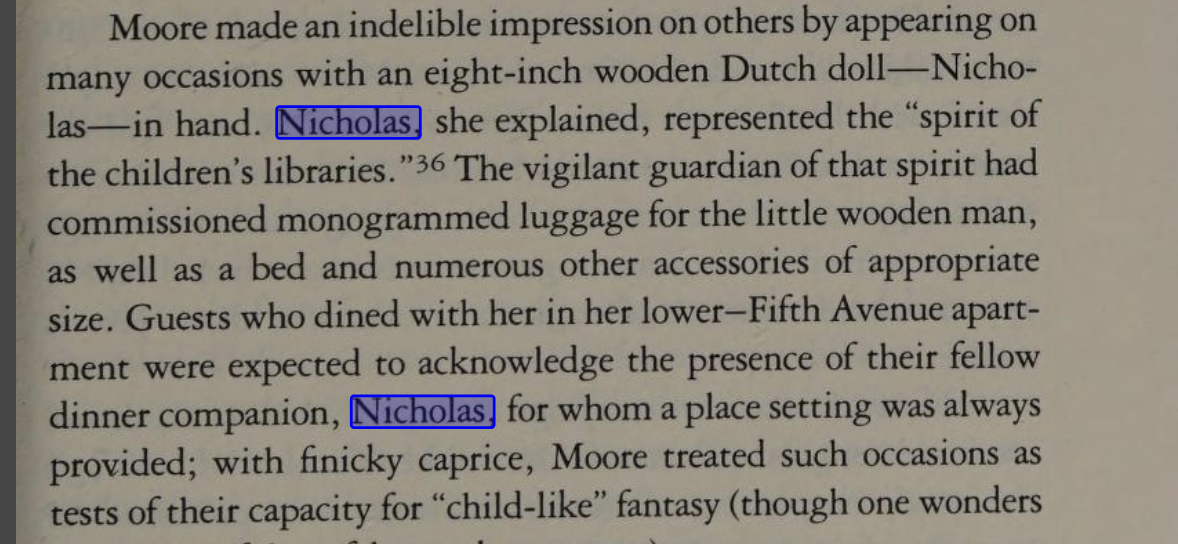

Anne Carroll Moore and her Doll Nicholas

The famous children's librarian Anne Carroll Moore was wont to tote around a doll named Nicholas and make people interact with it.

She eventually wrote a whole book (300+ pages) about Nicholas: Nicholas: A Manhattan Christmas Story.

You can read the book here.

I have tried in vain to find a real photo of Nicholas. However, here is his depiction from the book.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Mar 05, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Books, Libraries, 1920s, Dolls and Stuffed Animals, Mental Health and Insanity

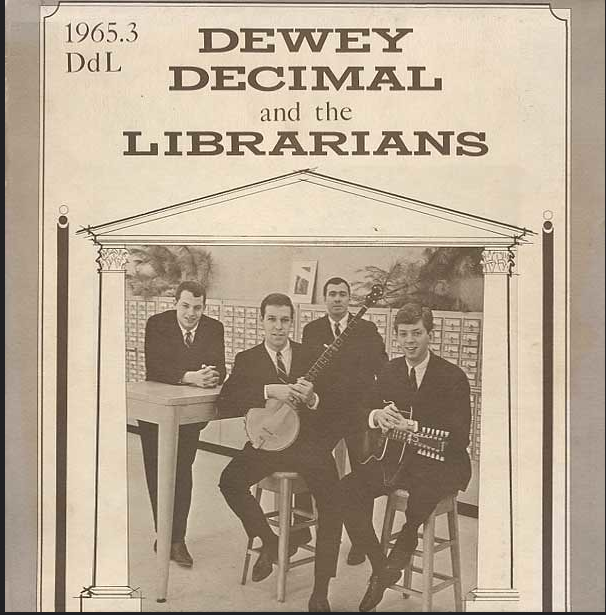

Dewey Decimal and the Librarians

Their entry at Discogs. Alas, no audio files available.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Apr 04, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Geeks, Nerds and Pointdexters, Music, Libraries, 1960s

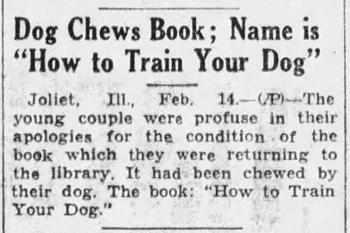

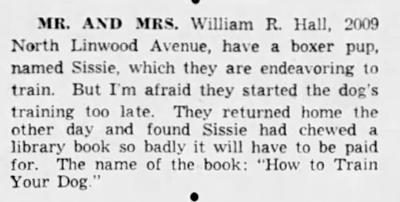

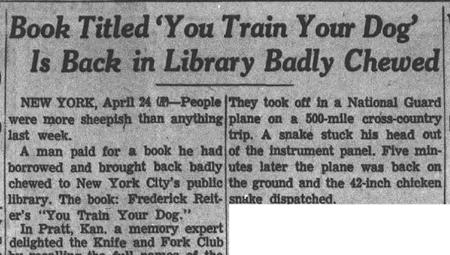

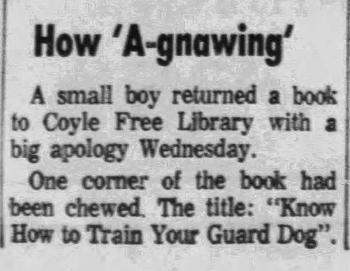

Dog chews ‘How to train your dog’

While browsing old newspapers, I've come across multiple reports of a book titled How to Train Your Dog being returned to libraries, chewed.These reports span thirty years, and specify different locations where this happened, but the stories are otherwise identical. So I figure that the chewed dog training book must be an urban legend of libraries.

Wausau Daily Herald - Feb 14, 1940

Indianapolis Star - May 24, 1951

Chattanooga Daily Times - Apr 25, 1955

Chambersburg Public Opinion - Mar 13, 1969

Posted By: Alex - Tue Dec 01, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Books, Libraries, Myths and Fairytales, Dogs

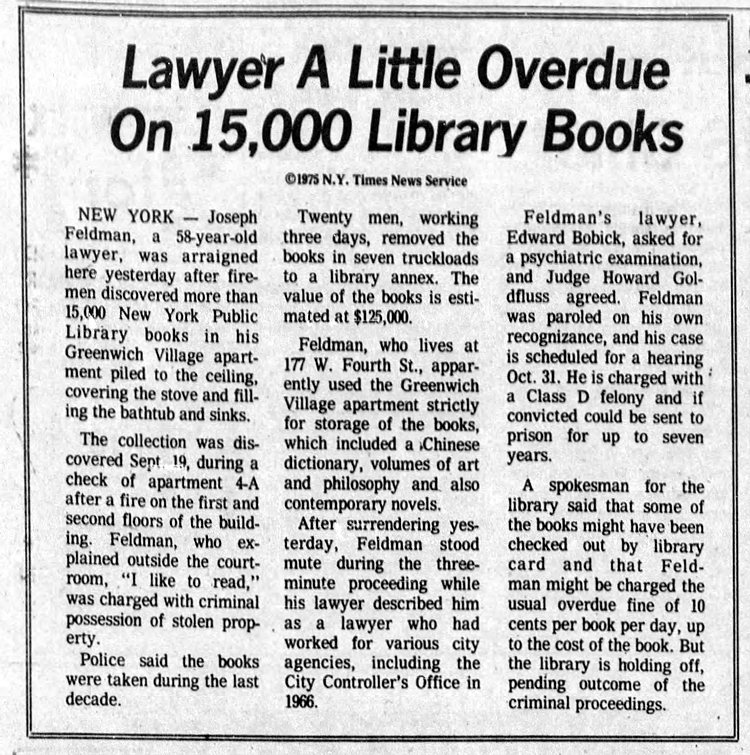

The man who stole 15,000 library books

Over the course of a decade, from around 1965 to 1975, Joseph Feldman managed to steal 15,000 books from the New York Public Library. He was caught when firemen entered his Greenwich Village apartment while responding to an alarm in his building and discovered all the books, piled up everywhere. When asked why he had taken them all, Feldman responded, “I like to read.”

Arizona Daily Star - Sep 27, 1975

In the 21st century, playwright Erika Mijlin was inspired to write a play, Feldman and the Infinite, about the incident. It was first performed in 2008. Her description of it:

And below, a video clip of the performance.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jan 31, 2019 -

Comments (2)

Category: Crime, Books, Libraries, Collectors, 1970s

Arthur Godfrey Sings MARIAN THE LIBRARIAN

An absolutely horrible version of a great song.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Dec 05, 2018 -

Comments (0)

Category: Ineptness, Crudity, Talentlessness, Kitsch, and Bad Art, Music, Libraries, 1950s

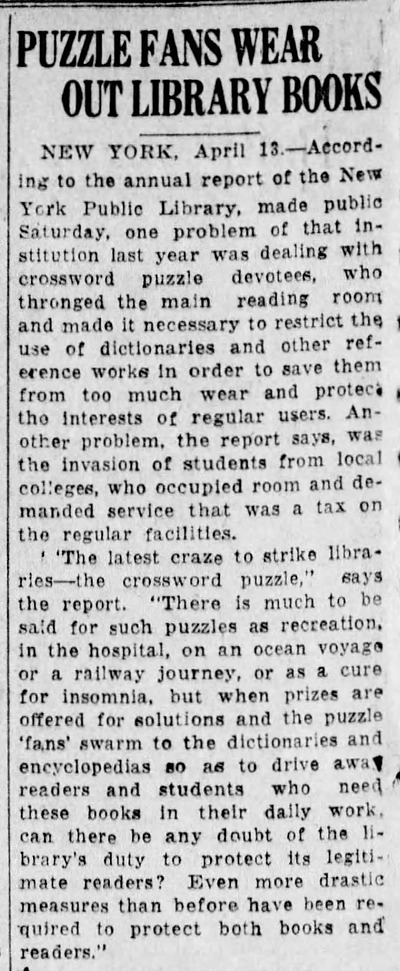

Puzzle devotees throng reading room

Crossword puzzles first became a fad in the 1920s, and immediately created a problem for libraries as puzzle devotees thronged reading rooms, putting a strain on library services, wearing out the various reference books, and generally being a nuisance to regular patrons of the library.

The Wilmington Evening Journal - Apr 13, 1925

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 21, 2018 -

Comments (4)

Category: Games, Libraries, 1920s

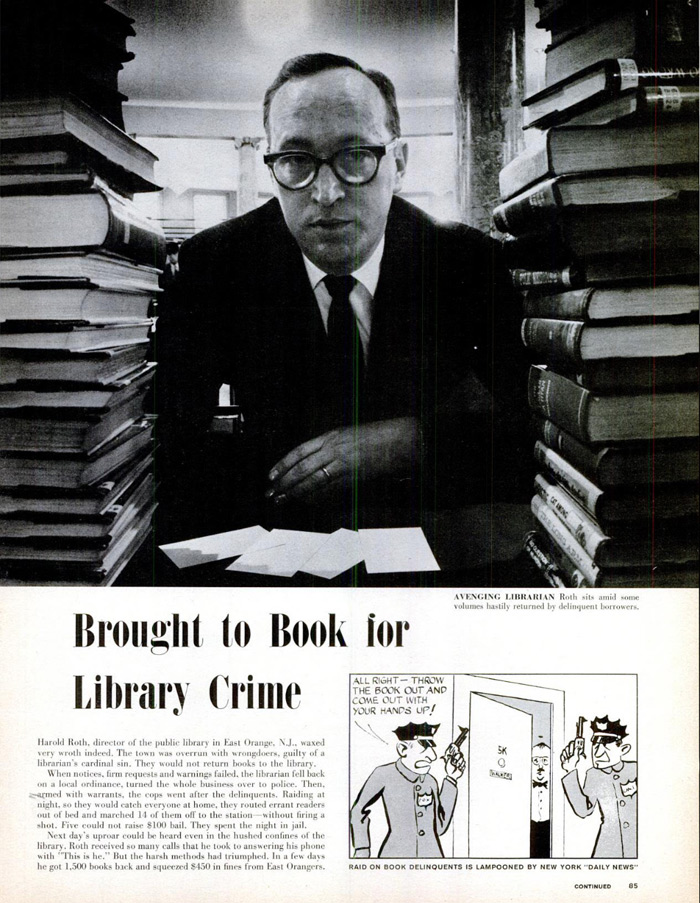

Librarian Strikes Back

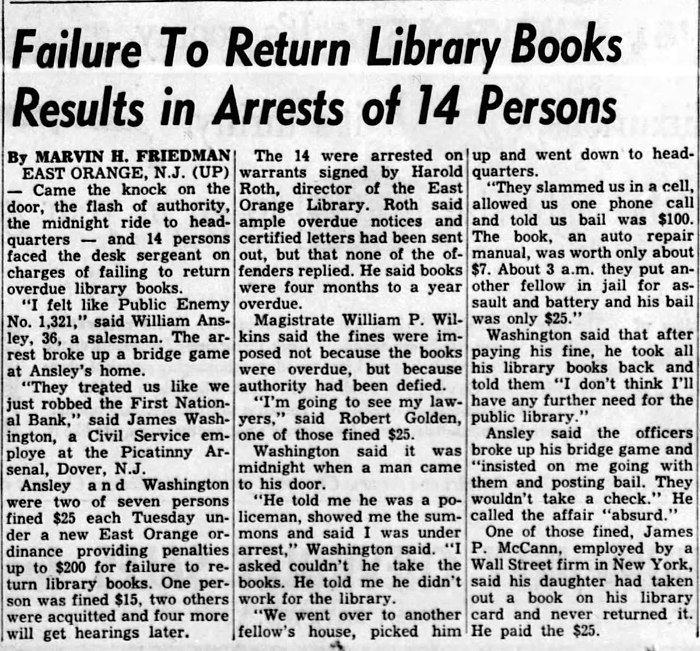

In February 1961, Harold Roth, director of the East Orange Library in New Jersey, made news by having arrest warrants made out for 14 people with overdue books. The degree of overdueness ranged from four months to one year. But what really attracted attention was the manner of the arrests. The police showed up at many of the houses around midnight to rouse the scofflaws out of bed and drag them down to jail.I think this 1961 case remains the largest mass round-up of people with overdue library books, but people still occasionally get arrested for not returning their library books in a timely fashion. The site publiclibraries.com has an article about "Jail time for overdue library books" that lists some more recent cases.

Life - Feb 17, 1961

Green Bay Press-Gazette - Feb 8, 1961

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 24, 2018 -

Comments (10)

Category: Crime, Libraries, 1960s

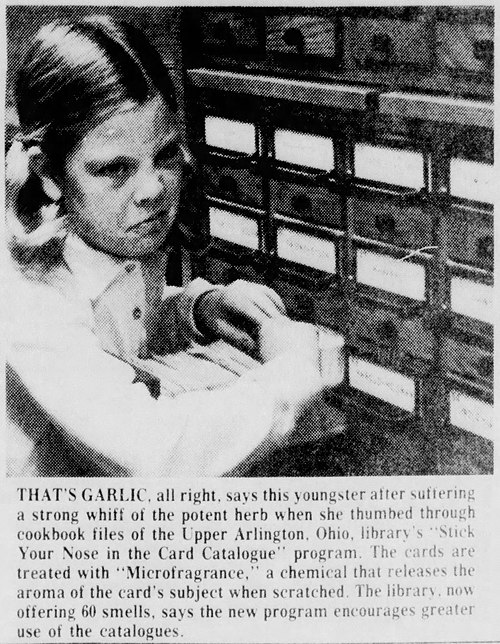

Fragrance-coded card catalog

In 1974, the public library in Upper Arlington, Ohio added scratch-and-sniff scents to its card catalog. They called it the "Stick Your Nose in the Card Catalogue" program.The idea was that the card in the catalog would have a scent, and then the book on the shelf would have a matching scent. So you could find your books by smell. There were about 60 scents in total, including apple, chocolate, garlic, lemon, roses, root beer, leather, pizza, orange, strawberry, candles, pine, cheddar cheese, clover, and smoke.

I was curious what became of the scented catalog, so I emailed the library and asked. The reply came just a few minutes later:

And they also emailed me a news clipping about the catalog (in extended, below) from the local Upper Arlington paper.

The Vernon Daily Record - Feb 9, 1975

San Antonio Express - Apr 11, 1976

More in extended >>

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 16, 2018 -

Comments (9)

Category: Libraries, 1970s, Perfume and Cologne and Other Scents

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |