1940s

Are you a Danger-Mother?

Danger Mother would be a good name for a band, if there wasn't already a band named Wolfmother.

Life - Mar 29, 1948

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jul 25, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Advertising, Parents, 1940s

The 1941 Slide Rule Queen

This honor was bestowed by my home state's university, the University of Rhode Island.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Jul 19, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Science, 1940s, Universities, Colleges, Private Schools and Academia

Bomb Proof Eye Guards

Mechanix Illustrated - Mar 1941

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jul 10, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: War, Weapons, 1940s, Eyes and Vision

Unauthorized Dwellings 34

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jul 01, 2024 -

Comments (1)

Category: Unauthorized Dwellings, 1940s, United Kingdom

Follies of the Madmen #599

Who knew that electrical appliances could be such rivals? And is that gal's Bride of Frankenstein hairdo a result of the scary radio mystery, or just her natural style?If you go to the source, you can magnify the text.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Jun 26, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Radio, Rivalries, Feuds and Grudges, Technology, Advertising, 1940s

Woodbury Rand, cat lover

When Boston attorney Woodbury Rand died in 1944, he left $40,000 to his cat Buster. Out of a $1,000,000 estate, that's not particularly unusual. But what made his will odd was that he disinherited anyone whom he felt hadn't properly appreciated Buster.Buster was only 8 years old when Rand died, but he died the following year. Perhaps of a broken heart?

New York Daily News - Aug 6, 1944

New York Daily News - Dec 30, 1945

Posted By: Alex - Sat May 11, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Inheritance and Wills, Cats, 1940s

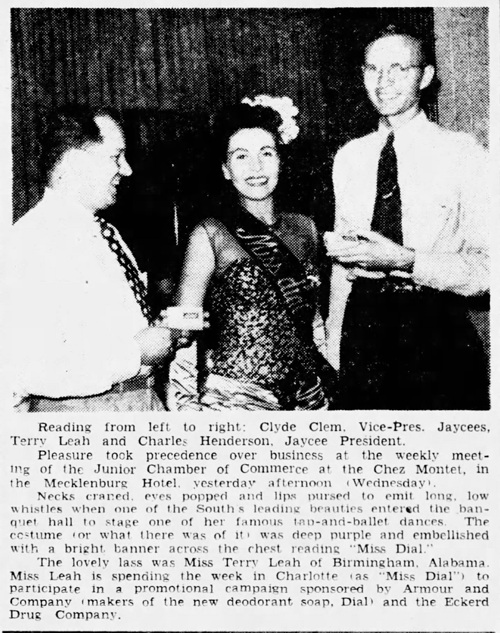

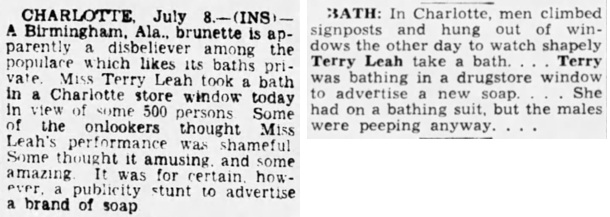

Miss Dial

In 1949, Terry Leah won the title of "Miss Dial" in a contest sponsored by Dial Soap. As far as beauty titles go, this one wasn't that unusual. But what was unusual was that, as part of the responsibility of being Miss Dial, Terry had to take a bath, using Dial Soap, in the window of Eckerd Drug Company in Charlotte, North Carolina.Adding to the public exposure, Dial promised that the person who took the best photo of Terry as she bathed would win $25.

Charlotte News - July 7, 1949

Charlotte Observer - July 8, 1949

Young Dickie Higgins was determined to win that prize. I'd bet that was the most exciting day of his life up until then. Unfortunately I haven't been able to find out who did win the photo prize.

"Dickie Higgins takes a shot of dancer Terry Leah, who is posing in a bubble bath in a Charlotte, North Carolina, store window advertising a new line of bath soap."

NY Journal American - July 28, 1949

(left) Greenville News - July 9, 1949; (right) Raleigh News and Observer - July 14, 1949

Posted By: Alex - Mon Apr 22, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Hygiene, Photography and Photographers, 1940s

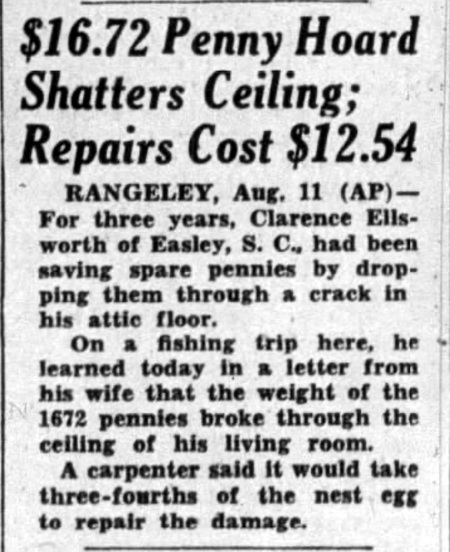

Saved pennies crash through ceiling

Aug 1947: Clarence Ellsworth had been saving pennies by dropping them through a crack in his attic floor. Finally, when the number of pennies reached 1,672, the weight of the pennies broke through the ceiling and landed in his living room.This raises the question: how much did 1,672 pennies weigh?

According to Wikipedia, pennies issued before 1982 each weighed 3.11 grams since they were made from 95% copper. After 1982, the U.S. Mint substituted a copper-plated zinc penny that weighed less.

3.11 times 1,672 comes out to 5200 grams (rounding up) — or approximately eleven and-a-half pounds.

I'm surprised that was enough to break his ceiling. Perhaps there were other issues, such as water damage, that contributed to the break.

According to an online inflation calculator, $16.72 in 1947 money would be worth $234.18 today. And the repairs would have cost approximately $175 (in today's money).

Bangor Daily News - Aug 12, 1947

Posted By: Alex - Tue Apr 16, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Money, 1940s

Tobacco Queen

Posted By: Paul - Sun Apr 14, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Smoking and Tobacco, 1940s

Bushells Tea: The City of Tomorrow

Posted By: Paul - Sat Apr 13, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Predictions, Yesterday’s Tomorrows, Soda, Pop, Soft Drinks and other Non-Alcoholic Beverages, 1940s, Australia

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |