Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters

The Radioactive Pup of Bikini Atoll

Operation Crossroads page at Wikipedia.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Mar 30, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Military, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, Dogs, 1940s, South Pacific

The Complacent Americans

One such gem is a Civil Defense "scare" album called THE COMPLACENT AMERICANS that simply must be heard to be believed. This LP - with its bright orange mushroom cloud cover and its hyperbolic advisories to sensitive listeners - could well have been produced by that genius of exploitation William Castle. But actually it was recorded under the stately auspices of the Office of Civil Defense, a sub-branch of the U.S. government (later replaced by FEMA).

Posted By: Paul - Thu Feb 29, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: PSA’s, War, Vinyl Albums and Other Media Recordings, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s

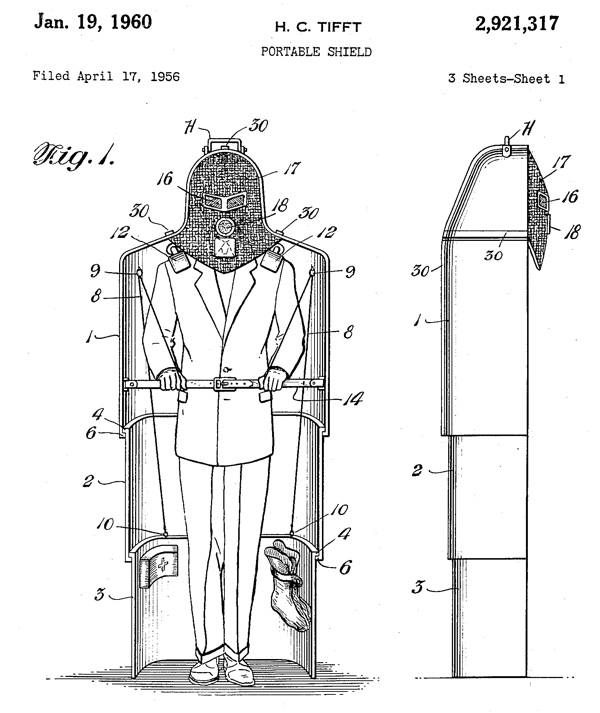

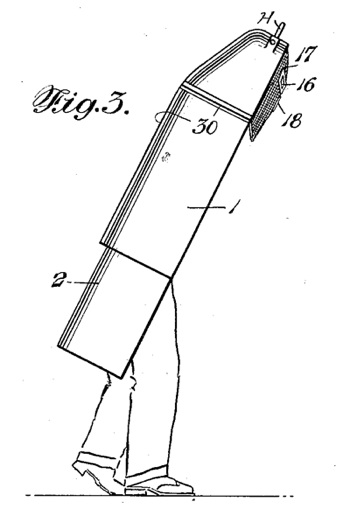

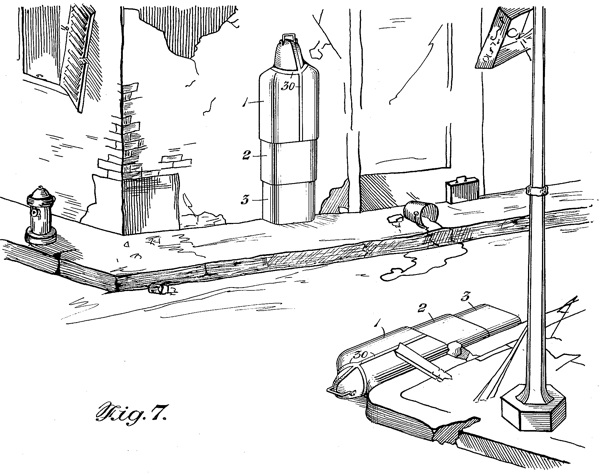

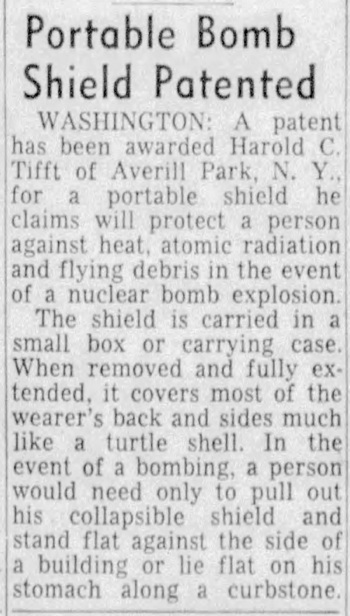

Harold Tifft’s Portable Nuclear Bomb Shield

Harold Tifft claimed that his portable shield would "protect the wearer against heat, atomic radiation, atomic fall-out and flying debris in the event of nuclear warfare." When not in use it fit inside a carrying case, but when needed it could be rapidly assembled into a full-body shield. From his patent:In his patent he never mentioned how much the thing weighed. Carrying the thing around constantly would surely have been a challenge.

Cincinnati Post - Jan 26, 1960

Posted By: Alex - Mon Feb 19, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Patents, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s

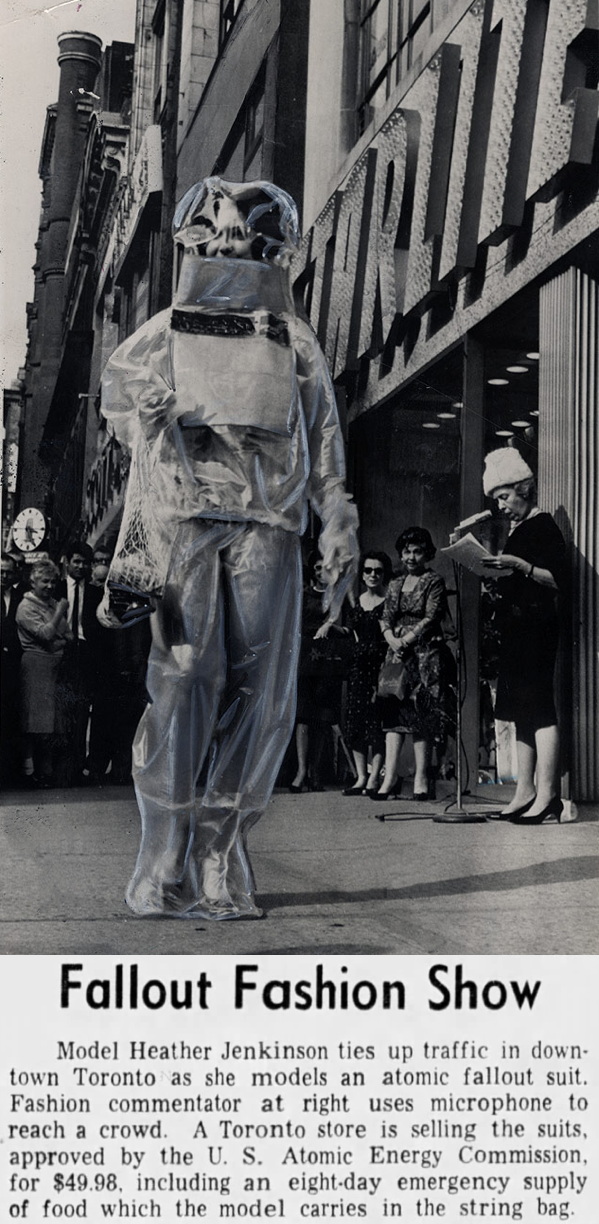

Fallout Fashion Show

It's no weirder than many of the outfits displayed at fashion shows nowadays.

Charlotte News - Oct 11, 1961

Posted By: Alex - Thu Feb 15, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Fashion, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s

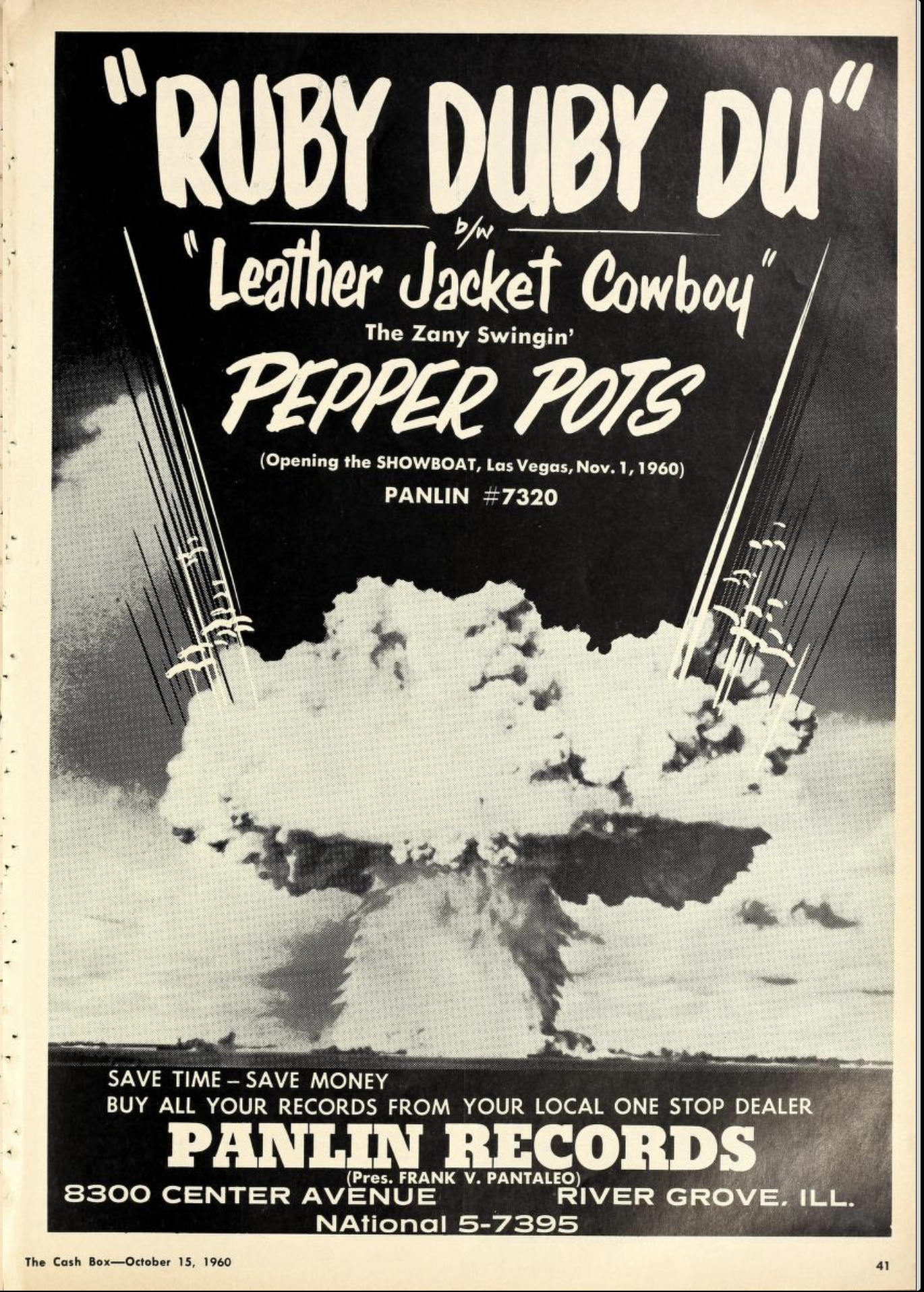

Follies of the Madmen #587

We have seen instances of this theme before: a giant nuclear mushroom cloud does not indicate death and destruction, but rather it shows your product is powerful.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Feb 07, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Death, Music, Advertising, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s, Weapons

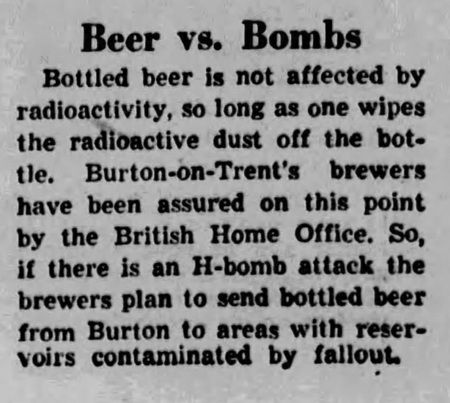

In the event of nuclear war, drink beer

Sounds like a sensible plan to me.As for whether bottles would protect the beer inside from radiation, I imagine that would be the least of one's concerns after a nuclear war.

Tacoma News Tribune - July 7, 1958

Posted By: Alex - Mon Jan 08, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inebriation and Intoxicants, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1950s

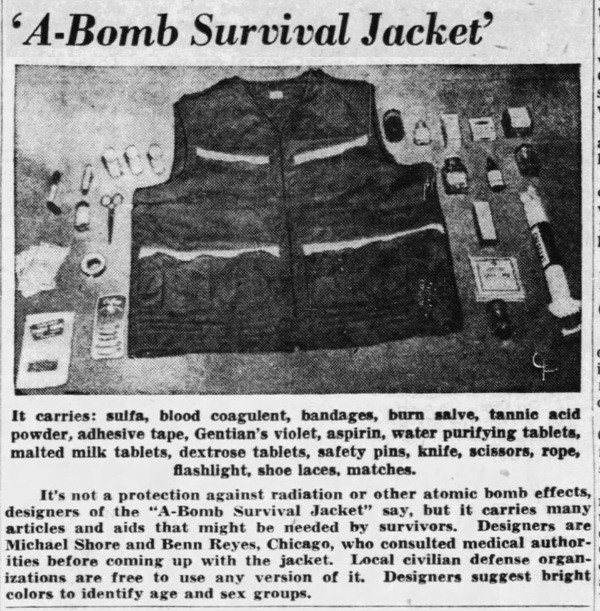

Atomic Bomb Survival Jacket

As the designers admitted, it wasn't going to protect anyone against an atomic bomb or radiation. But as a survival jacket it seemed pretty well equipped. Though a backpack full of the same stuff would seem to be more practical.

"Jean Shore displays inside pocket arrangement of survival jacket."

image source: Harry Ransom Center

Muncie Star Press - Jan 15, 1951

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jan 05, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Fashion, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1950s

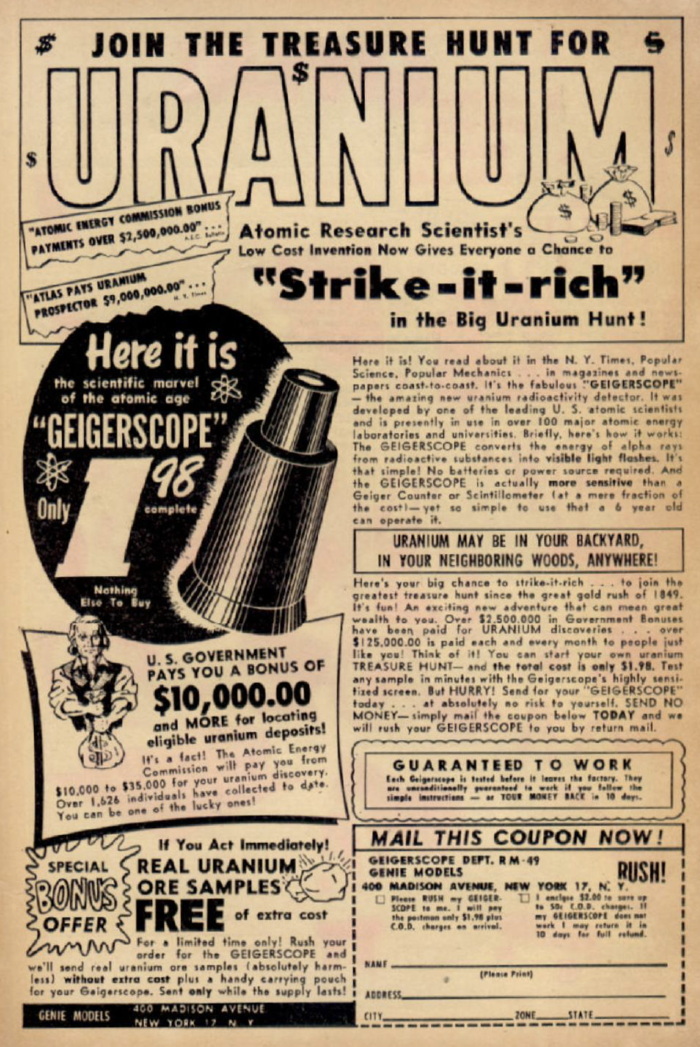

Uranium may be in your backyard

From what I can gather, this device (a 'geigerscope') would make visible the flashes of radiation given off by radioactive substances such as uranium. But (not mentioned by the ad) it only worked in complete darkness, with a dark-adapted eye. So not a practical way to hunt for uranium deposits.And if you had uranium in your backyard, you might wanna find somewhere else to live.

More info: periodictable.com

Posted By: Alex - Wed Dec 20, 2023 -

Comments (5)

Category: Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters

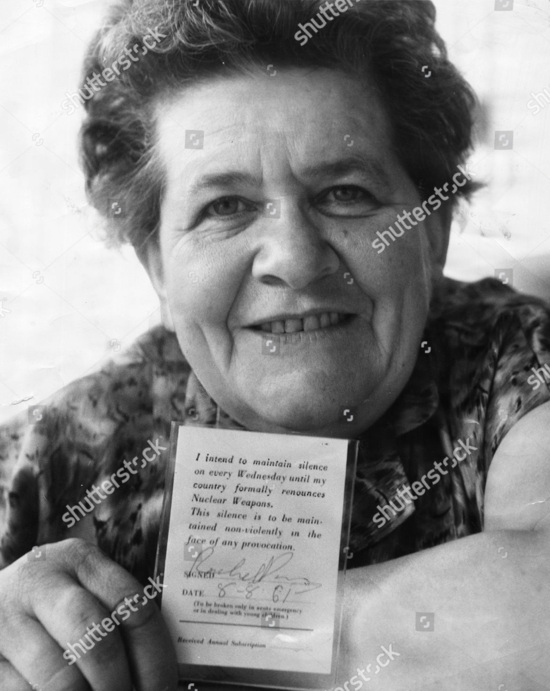

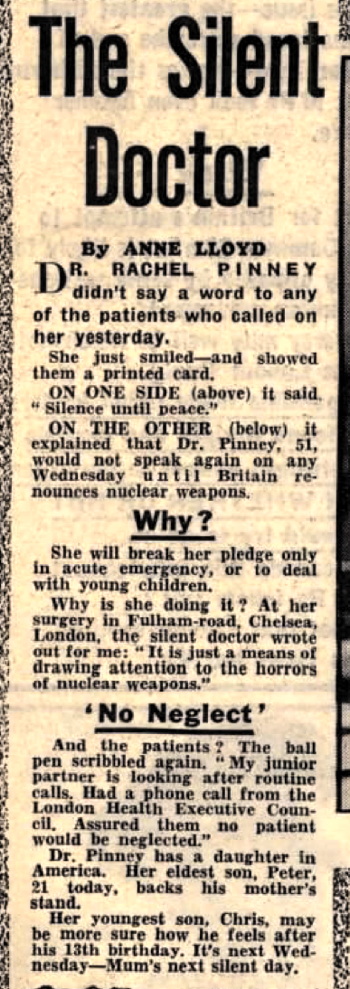

Rachel Pinney, the Silent Doctor

In August 1961, Rachel Pinney took the following vow: "I intend to maintain silence on every Wednesday until my country formally renounces Nuclear Weapons. This silence is to be maintained non-violently in the face of any provocation."Since Pinney worked as a medical doctor, her vow created some awkwardness with the patients she saw on Wednesdays. She had to communicate with them by means of nodding her head, hand signals, and notes (writing prescriptions).

According to her obituary, she maintained the vow for almost 30 years. Of course, the UK still has nuclear weapons.

Her once-a-week protest reminds me of Mildred Ruth Gordon who fasted every other day to show support for draft resisters.

Daily Mirror - Aug 10, 1961

Posted By: Alex - Wed Nov 29, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Riots, Protests and Civil Disobedience, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1960s

Home Fallout Shelter Snack Bar

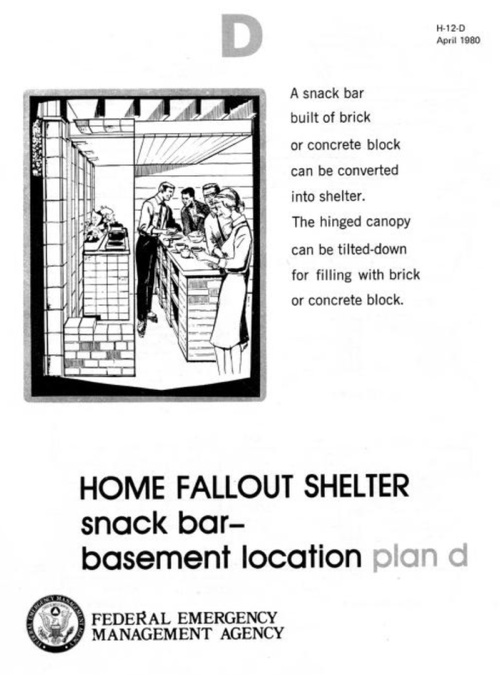

In 1980, FEMA published plans that allowed anyone to build their own Home Fallout Shelter Snack Bar. The plans are available at archive.org.

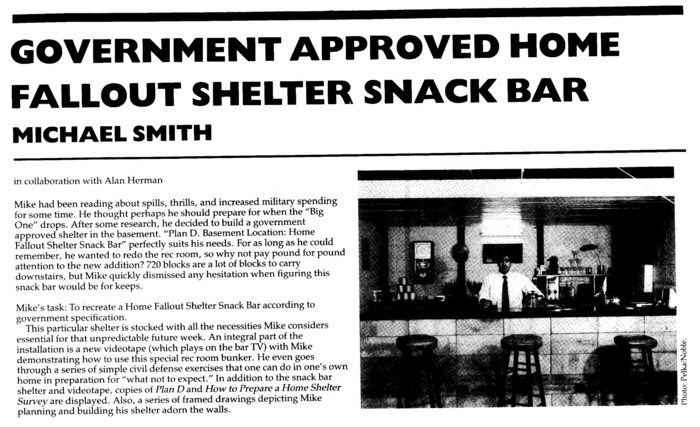

In 1983, artist Michael Smith followed FEMA's plans and built a Fallout Shelter Snack Bar, which he then displayed as an art installation. To accompany the snack bar, he also created a video game housed in a custom, upright arcade cabinet:

More info: rhizome.org

source: Video Installation 1983

Posted By: Alex - Sat Nov 11, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Art, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1980s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |