Patents

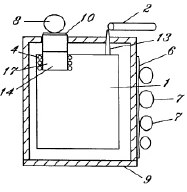

Burp Gas Filterer

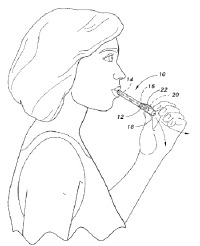

The Burp Gas Filtering Device: Patent No. 7070638, issued July 4, 2006. It serves two functions in one. You can deodorize your burp, and if your dinner companion needs a pen to sign the check, you'll have one to offer.

The Burp Gas Filtering Device: Patent No. 7070638, issued July 4, 2006. It serves two functions in one. You can deodorize your burp, and if your dinner companion needs a pen to sign the check, you'll have one to offer. The burp filtering device has the body of a writing pen, with an intake port at the upper end of the body, a plurality of exhaust ports adjacent the writing tip and a filter disposed within the body. The filter may be made of activated charcoal or other media for filtering and adsorbing or absorbing eructation odors. In use, the user holds the upper end of the pny body to his lips, releases the suppressed burp and the filtered, deodorized gas is exhausted through the ports at the writing tip...

Still another object of the invention is to provide a device for eliminating burp odors that also serves as a writing instrument.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Mar 09, 2009 -

Comments (11)

Category: Hygiene, Inventions, Patents

The Horse Life Preserver

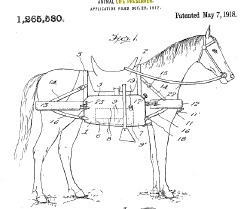

Patent No. 1265580, issued May 1918:

Patent No. 1265580, issued May 1918:This invention relates to life preservers, and more especially it is intended for quick application to a draft horse, pack mule, or other animal which is carrying war supplies and which may possibly be a cavalry horse, so that when a stream or river is reached the animal can swim across with his load and possibly with his driver and the necessity for building a bridge is avoided.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 04, 2009 -

Comments (10)

Category: Animals, Inventions, Patents

The history of three-holed panties

After I posted about the "pantyhose garment with spare leg" yesterday, several people pointed out prior art, which to my mind calls into question the validity of the patent.In the comments, Dumbfounded noted: "In a 1987 Judge Dredd story, the father of child serial killer P.J. Maybe shows off a design for trousers with a third leg, 'in case one wears out'. The spare leg was kept tucked in a pocket when not in use."

And then Chuck recalled that in the first News of the Weird paperback (1989), he included an anecdote from the Wall Street Journal about a Japanese worker who had invented six-day underwear with three leg holes.

I tracked down the WSJ article in question. It ran on Oct. 16, 1987 and described a creativity contest at Honda Motor Co. in which workers were encouraged to design whimsical new products, one of which was indeed underwear with three leg holes: "The garment is supposed to last for six days, with the wearer rotating it 120 degrees each day--and then wearing it inside out for three days."

Other products from the contest included:

- musical bath slippers

- a hot tub installed in the back of a car

- a fig tree that dances to the music of Karen Carpenter

- a toothbrush with built-in toothpaste

- a child's motorized sled that climbs back uphill by itself

- a pillow with an internal alarm

- and a rickshaw pulled by a manikin made of papier-mache and plaster (designed to resemble Honda's 81-year-old founder, Soichiro Honda)

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 27, 2009 -

Comments (8)

Category: Fashion, Underwear, Patents

Happy Cheese Parings Day

Let's take a moment to remember Thor Bjørklund, the Norwegian inventor of the cheese slicer. From Wikipedia:

Let's take a moment to remember Thor Bjørklund, the Norwegian inventor of the cheese slicer. From Wikipedia:And on this day, in 1925, he received a patent for the cheese slicer. According to blather.net, "27 February ever since has been celebrated as osteskorperdagen, 'cheese-parings day', the biggest holiday in the Norwegian calendar, when everyone gorges themselves on thin slices of cheese in the cold, icy streets."

Sounds to me like a good way to spend the day.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 27, 2009 -

Comments (8)

Category: Food, Holidays, Inventions, Patents

Pantyhose Garment with Spare Leg

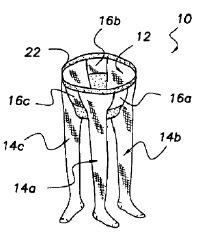

Patent No. 5,713,081, issued Feb 3, 1998:

Patent No. 5,713,081, issued Feb 3, 1998:In use the wearer inserts her legs into two of the leg openings in the conventional fashion of donning a pair of pantyhose. The remaining unused leg portion is then gathered and the toe end tucked into the pocket of one of the absorbent crotch members. If a run or hole develops in one of the leg portions being worn, the leg of the wearer can be easily and rapidly removed from the damaged leg portion and placed into the undamaged spare leg portion. The damaged leg portion is then gathered, folded and tucked into a pocket of one of the absorbent crotch members as wearer to select and use any two of the three leg portions for use.

All Weird Universe readers, male and female, are expected to add this to their wardrobes.

Posted By: Alex - Thu Feb 26, 2009 -

Comments (13)

Category: Fashion, Patents

Fetal Educator Strap

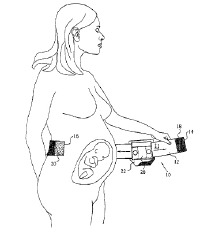

In the old days an "educator strap" was something teachers applied to a student's backside. (When I was a kid, some of my teacher's had canes which they used quite liberally, but I think that may be illegal now.)

In the old days an "educator strap" was something teachers applied to a student's backside. (When I was a kid, some of my teacher's had canes which they used quite liberally, but I think that may be illegal now.)However, this "fetal educator strap" (patent no. 6840775) is a learning system for fetuses while in utero:

I guess it's never too early to hook the kids on learning!

Posted By: Alex - Wed Feb 25, 2009 -

Comments (11)

Category: Patents

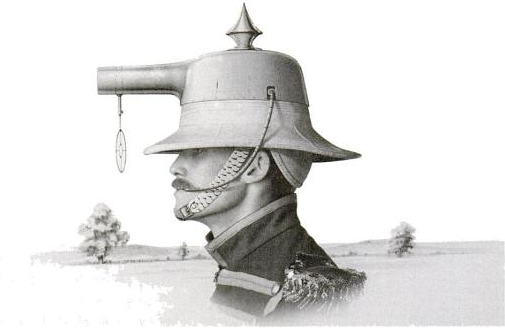

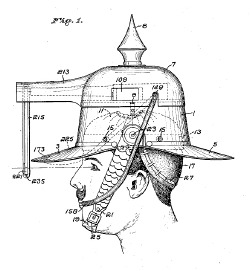

Albert Bacon Pratt’s Helmet Gun

In 1916 Albert Bacon Pratt of Lyndon, Vermont was issued patent No. 1183492 for a "gun adapted to be mounted on and fired from the head of the marksman." The wearer fired the gun by blowing into a tube. Most of Pratt's patent application is fairly dry and technical, but here he offers his thoughts on some of the advantages of his invention:

Pratt then points out that his invention is useful not only in combat, but also in the kitchen:

Pratt claimed he had solved the problem of recoil:

But I suspect he didn't have all the bugs ironed out, which must be why such a useful invention never caught on.

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 20, 2009 -

Comments (14)

Category: Inventions, Patents, Weapons

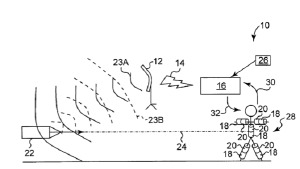

Bullet-Dodging Body Armor

IBM recently filed a patent describing body armor that actually dodges bullets. Don't leave home without it!

IBM recently filed a patent describing body armor that actually dodges bullets. Don't leave home without it!

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 17, 2009 -

Comments (8)

Category: Patents

Smoking-Cessation Lighter

Maybe I'm not understanding the invention, but it seems to me to be exactly the same as the electric-shock lighters that have been a favorite of pranksters for years. Except that the patent dresses up the prank with some scientific mumbo-jumbo. And instead of being conditioned not to smoke, wouldn't a smoker simply learn not to use that lighter? (Thanks to Sherry Mowbray!)

Posted By: Alex - Mon Aug 11, 2008 -

Comments (2)

Category: Inventions, Patents

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |