Geography and Maps

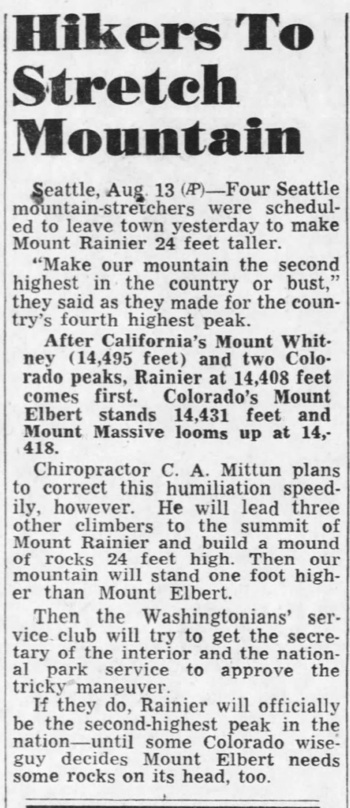

Raising Mt. Rainier

In 1948, Washington's Mt. Rainier was considered to be the fourth highest mountain in the U.S., behind California's Mt. Whitney and Colorado's Mt. Elbert and Mt. Massive. But the difference between Rainier and the Colorado mountains was only a few feet. So Seattle chiropractor (and mountain-climbing enthusiast) C.A. Mittun came up with a plan to build a 24-foot mound of rocks on top of Mt. Rainier, thereby leapfrogging it from fourth place into second.However, their plan never came to fruition. A Colorado-born park superintendent stopped Mittun and his team on their way up, telling them that their plan was illegal.

None of the articles from 1948 about Mittun's plan mentioned Colorado's Mt. Harvard, which Wikipedia lists as being four-feet higher than Mt. Rainier. So sometime between 1948 and now the relative heights of the two mountains must have been adjusted, pushing Mt. Rainier further down the list. When Alaska became a state in 1959, Mt. Rainier fell far down the list to its current spot at #17.

Incidentally, Mt. Harvard has its own history of being artificially raised. In the 1960s a group of Harvard graduates put a 14-foot flagpole on its summit in order to make it the second highest point in the contiguous United States. The flagpole stayed up for about 20 years.

Santa Cruz Sentinel - Aug 13, 1948

Hanford Morning Journal - Aug 17, 1948

Posted By: Alex - Tue Dec 19, 2023 -

Comments (4)

Category: Geography and Maps, Landmarks, 1940s

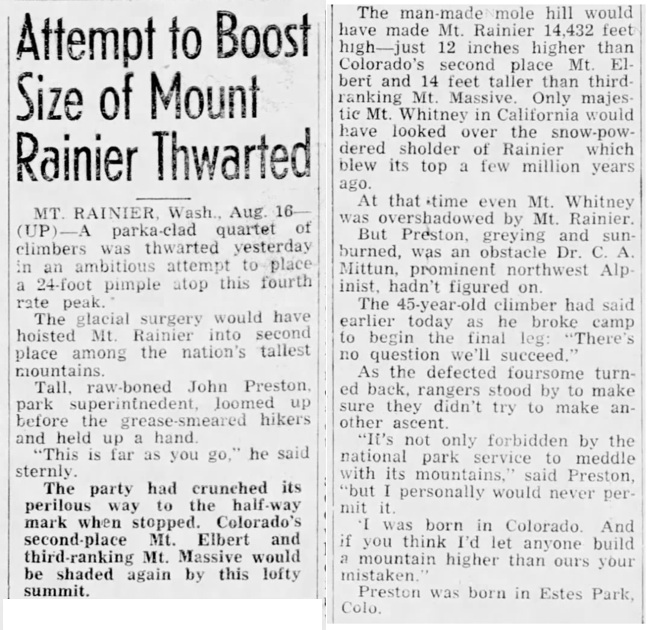

Corner-Locked Lands

Oct 2021: Four hunters were charged with criminally trespassing on the Elk Mountain Ranch in Wyoming. The curious thing was that everyone, including the prosecution, agreed that the hunters had never set foot on the ranch. However, the owner of the ranch alleged that the bodies of the hunters had briefly passed through the airspace immediately above his ranch.OnXMaps.com explains:

The underlying issue was that of corner-locked public lands. Throughout the western states many public and private lands border each other in a checkerboard pattern. As a result, the only way to get to some public lands is via the corner. But you can't step over the corner from one public land to another without simultaneously having part of your body pass through airspace that's private property. And many private property owners strongly object to people doing this.

Some 8.3 million acres of public lands are estimated to be "corner-locked" in this way.

A jury eventually found the hunters not guilty of criminal trespass. But the owner of the ranch then filed a civil suit against them, which is still ongoing. He's seeking $9.39 million in damages for their violation of the airspace above his ranch.

More info: WyoFile.com

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jan 12, 2023 -

Comments (9)

Category: Geography and Maps, Lawsuits

Travel through Europe in Ohio

If you want to visit Venice, Rome, Warsaw, Dublin, Berlin, Amsterdam, or Vienna, there's no reason to leave the United States. In fact, one could visit all these places without going outside the borders of Ohio.This is because Ohio has many cities and towns named after cities in Europe. Far more than any other U.S. state. You can find all the city names listed above in Ohio, plus many more. Think of a European city, and there's probably a town in Ohio with the same name.

Some people go on tours of European cities in Ohio, in lieu of actually going to Europe.

H2G2.com explains why Ohio has all these copycat names:

However, Ohioans have put their own unique stamp on many of these copycat names by pronouncing them differently. For instance, Milan, Ohio is pronounced "MY-lun". Some more Ohio pronunciations:

- Lima (LY-ma)

- Versailles (ver-SAILS)

- Moscow (MAHS koh)

- Russia (ROO she)

- Vienna (veye EH nuh)

- Berlin (BUR lynn)

More info: 20 Ohio Towns You're Probably Pronouncing Wrong

Posted By: Alex - Fri Mar 11, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Geography and Maps, Odd Names

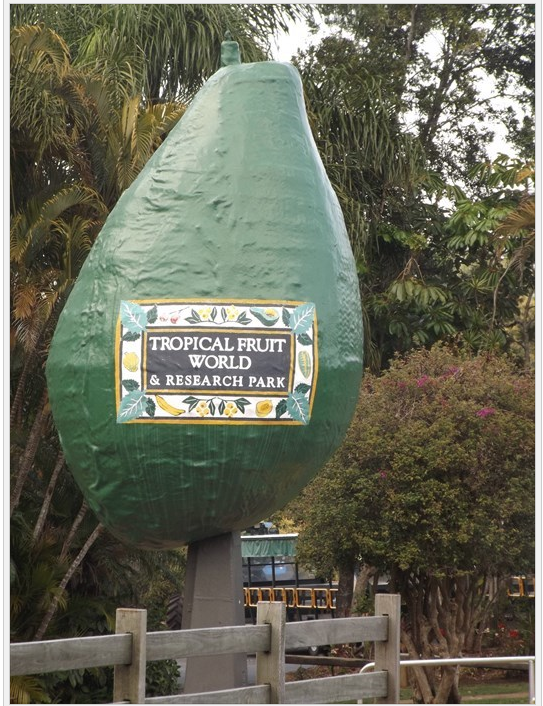

Waymarking

The Waymarking site allows the user to add a geo-tag to any object or place to make it findable by anyone else.They have their entries grouped into categories, and certainly the Oddities subgroup will be of interest to WU-vies.

There you can find, among other things, giant commercial icons such as the one below.

Posted By: Paul - Thu Oct 08, 2020 -

Comments (1)

Category: Food, Geography and Maps, Advertising

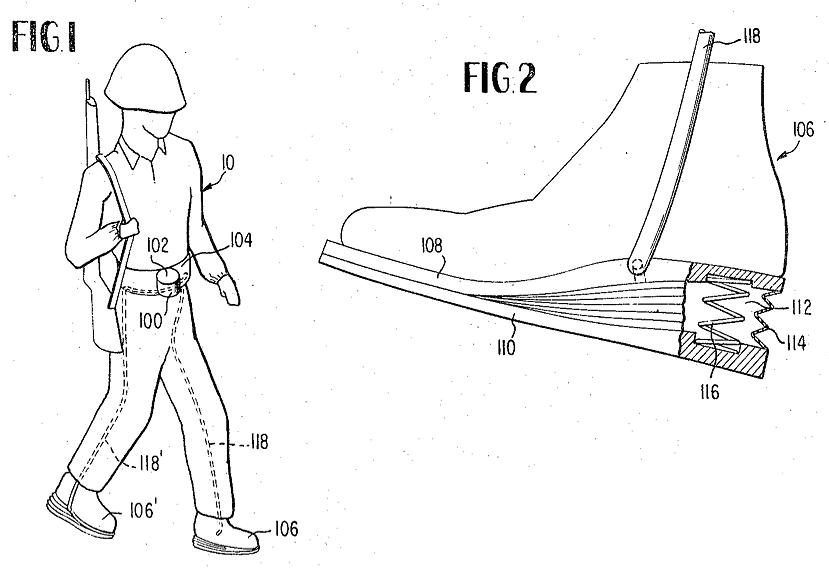

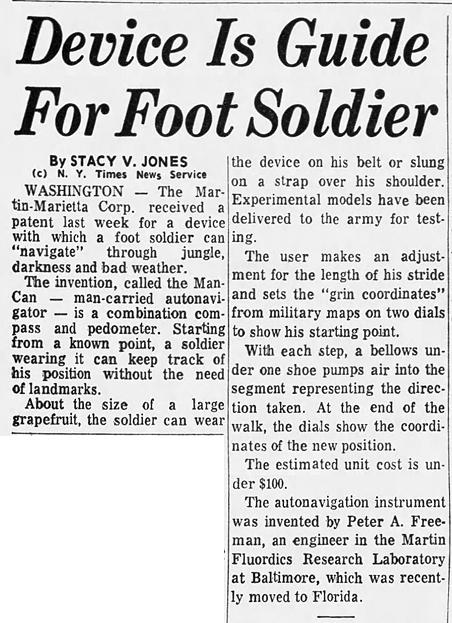

The Man Can

Its formal name was the “man-carried auto-navigation device,” but it went by the nickname “Man Can.” The Martin-Marietta Corporation received patent no. 3,355,942 for it in 1967.It was a device designed to help soldiers avoid getting lost. The patent offered this description:

It combined a compass and a pedometer. A GI would record his initial location on a map, and then the device would track his footsteps and the directions in which he turned. When he was done walking, the device would tell him his new coordinates.

A key feature of the device was that it didn't use any battery power. So the GIs would never need to worry about it running out of juice. It operated via a bellows located in the heel of the GI's shoe.

I can't find any follow-up reports about how well this gadget worked. Apparently not well enough to warrant its adoption by the army. But it was an interesting concept.

Allentown Morning Call - Dec 11, 1967

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jan 05, 2020 -

Comments (4)

Category: Geography and Maps, Inventions, Patents, Military, Technology, 1960s

The Bielefeld Conspiracy

Ever since 1993, a conspiracy has circulated online alleging that the German city of Bielefeld doesn’t exist. Now the city is pushing back by offering a million euros to anyone who can definitively prove it doesn’t exist.Entries can be submitted in either German or English, but the deadline is Sep. 4. So there’s not much time left.

It seems to me that the contest has set an impossible task, because it's well known that a negative can never be proven. For instance, we can't definitively prove that the Loch Ness Monster doesn't exist. We can only say that we haven't found her yet.

But on the other hand, the opposite is equally true. It's impossible to definitively prove anything with absolute certainty. For instance, what if someone believes that Bielefeld exists because they've lived there their entire life? Well, that doesn't actually prove anything. As Bertrand Russell pointed out in his five-minute hypothesis, it's possible that the entire universe sprang into existence five minutes ago, complete with our memories of an older history. It may seem unlikely, but it's possible. So likewise, just because someone remembers living in Bielefeld, it's possible that their memories are false.

Which is to say that even if no one wins the million euros by proving that Bielefeld doesn't exist, that doesn't mean the city actually does exist. The existence of Bielefeld can never be definitively proven or disproven.

More info: epoch times

Posted By: Alex - Fri Aug 30, 2019 -

Comments (1)

Category: Awards, Prizes, Competitions and Contests, Geography and Maps, Conspiracy Theories and Theorists

Stedman Whitwell’s Rational System of Nomenclature

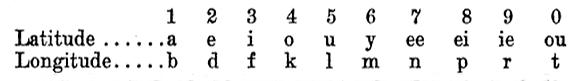

Back in the 19th century, English architect Stedman Whitwell decided that there must be a way to name cities and towns that could not only provide a unique name but also convey geographic information. His idea, as described by George Browning Lockwood in The New Harmony Communities (1902):

The first part of the town name expressed the latitude, the second the longitude, by a substitution of letters for figures according to the above table. The letter “S” inserted in the latitude name denoted that it was south latitude, its absence that it was north, while “V” indicated west longitude, its absence east longitude.

Extensive rules for pronunciation and for overcoming various difficulties were given. According to this system, Feiba Peveli indicated 38.11 N., 81.53 W. Macluria, 38.12 N., 87.52 W., was to be called Ipad Evenle; New Harmony, 38.11 N., 87.55 W., Ipba Veinul; New Yellow Springs, Green county, Ohio, the location of an Owenite community, 39.48 N., 83.52 W., Irap Evifle; Valley Forge, near Philadelphia, where there was another branch community, 40.7 N., 75.25 W., Outeon Eveldo; Orbiston, 55.34 N., 4.3 W., Uhi Ovouti; New York, Otke Notive; Pittsburg, Otfu Veitoup; Washington, Feili Neivul; London, Lafa Vovutu.

The principal argument in favor of the new system presented by the author was that the name of a neighboring Indian chief, “Occoneocoglecococachecachecodungo,” was even worse than some of the effects produced by this “rational system” of nomenclature.

I think the chart above is slightly misleading, as it implies that the top line is for latitude and the bottom for longitude. But if you look at the names Whitwell was coming up with, it's clear that this wasn't the case. It seems, instead, that one had to choose whether to start the name with a vowel (top line) or consonant (bottom line).

If I've understood his system correctly, then the 'rational' name for San Diego (32.71 N, 117.16 W) could be Fena Baveeby. And Los Angeles (34.05 N, 118.24 W) could be Fotu Avapek.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 20, 2019 -

Comments (4)

Category: Geography and Maps, Odd Names, Nineteenth Century

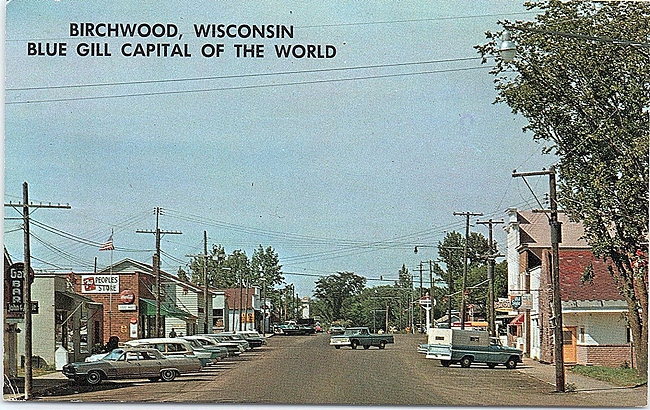

Blue Gill Capital of the World

Was this really the best scene of the "vacation paradise" of Birchwood, Wisconsin that the maker of this 1970s-era postcard could come up with? And where are the blue gills?.Here's (what I think is) the present-day view on Google Maps.

Source: eBay

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jan 12, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Geography and Maps, Tourists and Tourism, 1970s

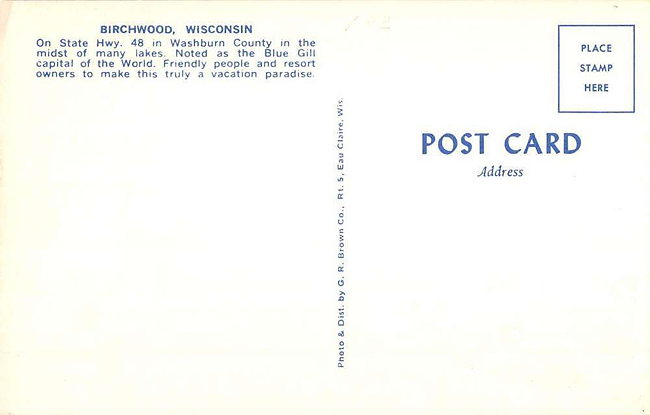

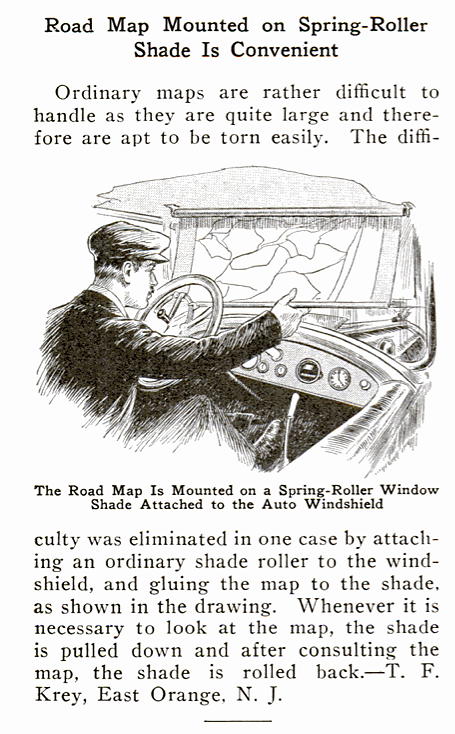

GPS of the 1920s

I can think of one obvious problem with mounting the map in front of the windshield.

Posted By: Alex - Mon Nov 26, 2018 -

Comments (2)

Category: Geography and Maps, 1920s, Cars

Statehood for Lake Michigan

Back in 1975, Federal Administrative Judge Edward McCarthy briefly tried to promote the idea of granting statehood to Lake Michigan. He figured that if the lake itself was a state, then all the surrounding states wouldn't be able to exploit its resources as easily. As for the oddness of a lake being a state, he reasoned, why not? "After all," he noted, "it's a piece of real estate on which a body of water rests."

Waukesha Daily Freeman - Mar 10, 1975

Posted By: Alex - Sun Oct 08, 2017 -

Comments (1)

Category: Geography and Maps, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |