Human Marvels

Bebe Stanton, Telepathic Flapper

Source: The Courier (Waterloo, Iowa) 11 Apr 1929, Thu Page 13

Posted By: Paul - Fri Apr 22, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Crime, Frauds, Cons and Scams, Human Marvels, 1920s

René Lavand, One-Armed Magician

His Wikipedia page.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Apr 10, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Disabilities, Human Marvels, Magic and Illusions and Sleight of Hand, Television, 1960s

Angelo Faticoni, the Human Cork

We've previously posted about two people who claimed to be "human corks": Norris Kellam and Iver Johnson.Now I've found a third to add to the list: Angelo Faticoni.

The lives of Kellam and Faticoni overlapped, but I can't find any evidence that they ever met.

More info: wikipedia

Johnson City Chronicle - July 24, 1926

Hartford Courant - Aug 12, 1931

Posted By: Alex - Sat Apr 09, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Human Marvels, Swimming, Snorkeling, and Diving

The Frozen Woman

Dec 20, 1980: On a cold winter's evening, 19-year-old Jean Hilliard's car got stuck in a ditch, so she decided to walk for help. She was found the next morning, two miles away, frozen solid.Remarkably, doctors were able to thaw her out even though she was so rock hard that needles broke on her skin. She suffered no serious injuries — just some blistered toes.

Read the full story at MPR News

Posted By: Alex - Wed Mar 16, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Human Marvels, 1980s, Weather

The Princess Rajah Dance

Man, that gal's got some strong jaws--as you will see!

Posted By: Paul - Sun Mar 06, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Furniture, Human Marvels, 1900s, Dance

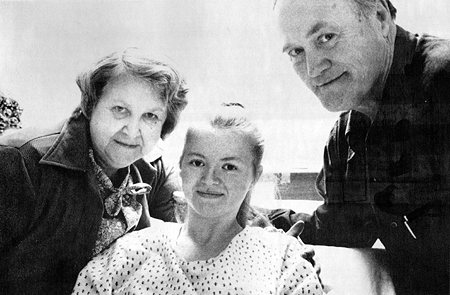

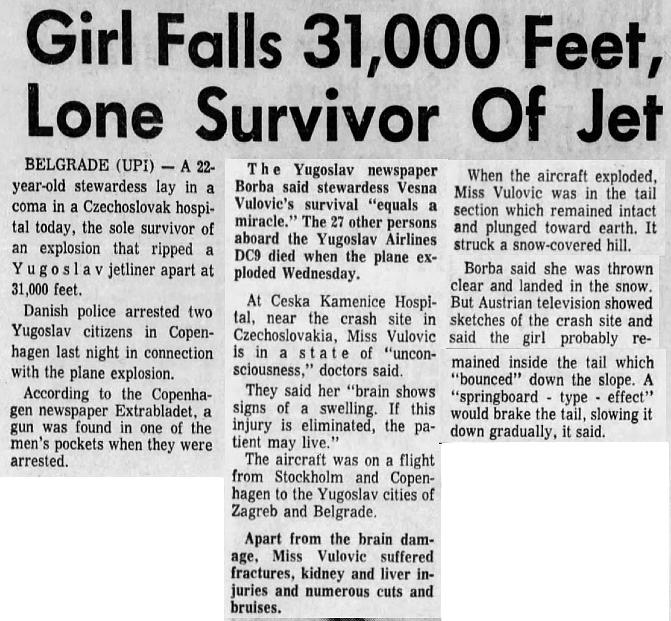

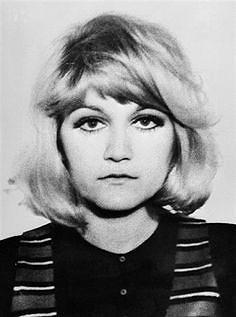

Longest fall without a parachute

We've recently had a couple of posts about people surviving long falls. So this post (originally from Jan 2021) seemed relevant.On January 26, 1972, stewardess Vesna Vulovic was working on a Yugoslav Airlines flight when a bomb blew up the plane. She fell 31,000 feet and miraculously survived. No one else on the flight did. She eventually made a near-full recovery and went back to work at the airline, though not as a stewardess. She died in 2016. To this day, she maintains the world record for having made the longest fall without a parachute.

Pittsburgh Press - Jan 29, 1972

Vesna Vulovic. Source: wikipedia

Vulovic is part of a small group of human marvels who have survived very long falls. Another member of this group is English tail gunner Nicholas Alkemade who, in 1944, survived a fall of 18,000 feet out of a Lancaster bomber.

The question of how people are able to survive very-high falls has attracted some scientific interest. The most famous study on this topic, that I'm aware of, was published by Hugh De Haven in 1942: "Mechanical analysis of survival in falls from heights of fifty to one hundred and fifty feet". I've pasted a summary of his study below, taken from Newsweek (Aug 24, 1942). But basically his conclusion was that, if you're falling a long distance, hope that something breaks and cushions your fall.

Obviously, De Haven couldn't subject human guinea pigs to experimental accidents in a laboratory. Instead, he analyzed the records of some remarkably lucky and well-documented falls—cases where men and women dropped from as high as 320 feet (the equivalent of 28 stories) and survived. A few of them:

--A 42-year-old woman jumped from a sixth floor. Hurtling 55 feet, she landed at 37 miles an hour on her left side and back in a well-packed plot of garden soil. She arose with the remark: "Six stories and not even hurt." Her body had made a 4-inch hollow in the earth.

--A 27-year-old girl dropped from a seventh story window and landed head first on a wooden roof. She crashed through, breaking three 6- by 2-inch beams, and dropped lightly to the ceiling below. None of her neighbors knew about the fall until she herself appeared at the attic door and asked assistance. And although one of her vertebrae was fractured, the girl was able to sit up in bed the same day.

--Another woman fell 74 feet, landing flat and face down on an iron bar, metal screens, a skylight, and a metal-lath ceiling. The impact made a 13-inch bend in the 1.5-inch bar, but she suffered only some cuts on her forehead and soreness about the ribs. She sat up and climbed through a nearby window.

--After a 72-foot drop, a 32-year-old woman landed in jackknife position on a fence of wire and wood. She picked herself up and marched to a first-aid station but was unhurt.

--A 27-year-old man fell 146 feet onto the rear deck of a coupe. Some of his bones were broken, but he remained conscious and was back at work within two months.

--A man dropped from a 320-foot cliff to the beach below, bouncing from a sloping ledge halfway down. Although his skull was fractured, he fully recovered. DeHaven noted that the man wore a large coat, which may have slowed his fall by a slight parachute action.

--A woman fell seventeen floors onto a metal ventilator box, landing in sitting position and crushing the metal downward 18 inches. Though both arms and one leg were broken, she sat up and demanded to be taken back to her room.

In this evidence, De Haven observed that (1) in each instance the blow was distributed over a large area of the body, and (2) the fall was not halted abruptly—in the ventilator case, for example, it was slowed through a distance of 18 inches and the impact was thus decreased. Even so, she had survived a force of more than 200 times gravity. By contrast, a person slipping on a sidewalk might crack his skull because hitting the unyielding concrete pavement generated a force of more than 300 times gravity.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Feb 05, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Human Marvels, World Records, 1970s

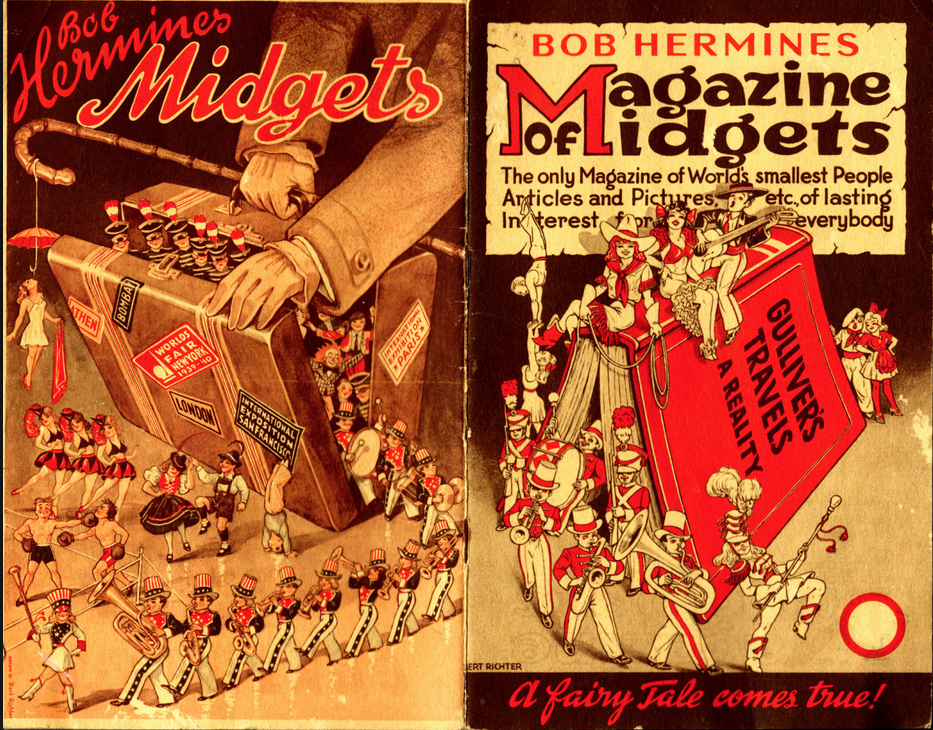

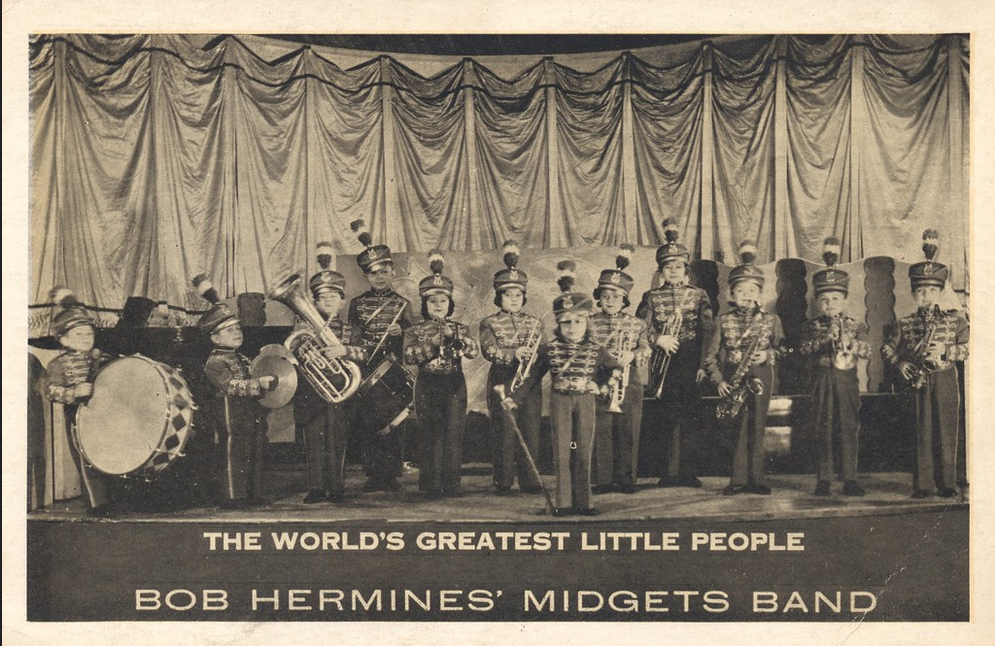

Bob Hermines’s Midgets Band

At this link, you will find several digitized pages from their official handbook.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Jan 29, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Human Marvels, Music, Twentieth Century, Differently Abled, Handicapped, Challenged, and Otherwise Atypical

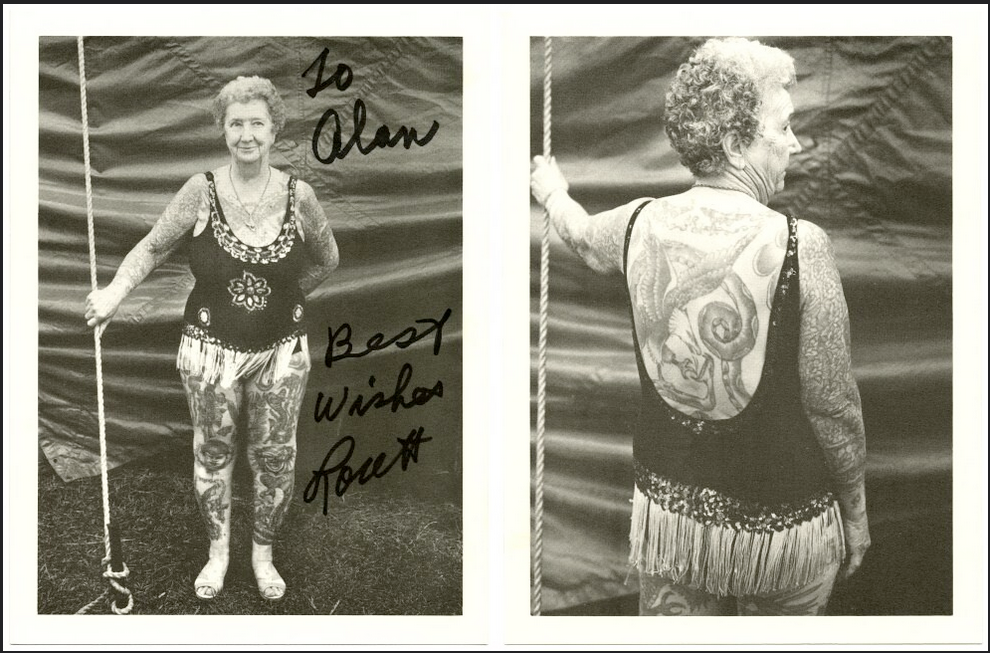

Lorett Fulkerson, the Last Performing Tattooed Lady

Was this gal, still performing in the 1990s, the last of her kind, an old-fashioned circus/sideshow performer? Maybe some current hipster performance piece features a tattooed female of this caliber. But it seems unlikely, so common is tattooing these days, even to the similar extent of Lorett's body, 90% inked.Some info at her Find A Grave site.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Jan 18, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Human Marvels, Tattoos, Twentieth Century, Circuses, Carnivals, and Other Traveling Shows

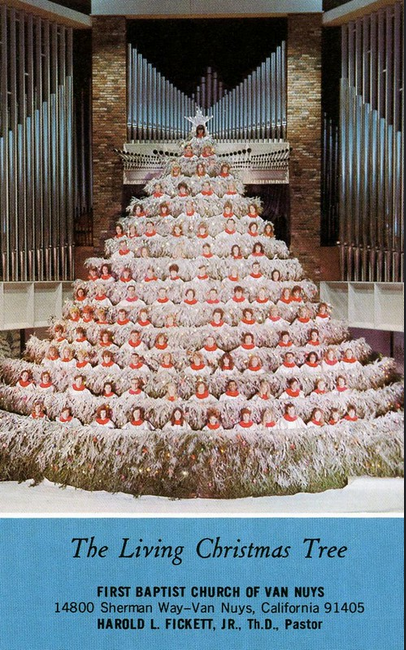

The Living Christmas Tree

Alex and I will be making an announcement soon, about where all WU-vies can meet up to form such a seasonal tribute. Bring your own robe.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Dec 15, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Holidays, Christmas, Human Marvels, Twentieth Century

The man who could read record grooves

Dr. Arthur Lintgen had an unusual talent. By looking at the grooves on a vinyl record, he could identify what the recording was. Within limits. It had to be classical music (no rock 'n' roll), preferably from the time of Beethoven up to the present. And it had to be a complete recording. Not an excerpt. But within those parameters, he was pretty much flawless.You can see him in action in the clip below.

Some more info from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Aug 5, 1980):

Ridiculous.

My editor broke out in laughter. Colleagues howled with scorn. I just smirked a little.

Laugh no more, lest Arthur B. Lintgen M.D. make you chew on your ridicule and swallow every smirk. Lintgen indeed possesses this astonishing talent. Its value, granted, is dubious in terms of mankind's future — nothing like a cure for cancer or a peace formula for Palestinians.

But if you cherish astonishment for its own sake, then watch Lintgen first as he fondles a record, holding it perpendicularly at nose level, frowning at its surface, and then as he looks up smiling brightly: "Why, yes. This is a favorite of mine, the Rachmaninoff Second Symphony."

...

[Lintgen] shies away from the pressures of a betting situation, preferring to keep his "eccentric hobby" an affair for friends and family. He is also quick to point out that his prowess is not universal, and that there are ground rules and limitations to what he can do.

First, the music must date from the time of Beethoven up through the present, the avant-garde excluded. Lintgen cannot precisely identify music he does not know or has no sympathy for. Secondly, no solo instruments or chamber music — where groove patterns, he says, fluctuate too widely to be read. Thirdly, he must know if the recording is a complete work with a fixed number of movements. No excerpts, please.

What then follows seems to be a combination of musical and technical erudition, some inspired deductive reasoning, and something else I am at a loss to isolate — perhaps a gift not unlike the sense of perfect pitch possessed by many gifted musicians.

The Haydn Symphony, No. 100 is outside Lintgen's prescribed ground rules (too early), but we asked him to look at it anyway. The process was illuminating.

• The four bands on the record surface suggested to him the four movements of the classical symphony. This was reinforced by the patterns on band three which indicated to him the A-B-A minuet form of this genre.

• The mirror-like ⅜-inch beginning the side told him "slow, quiet introduction" for which Haydn symphonies are noted. Grooves reveal to Lintgen nothing about pitch, but they do seem to tell him a great deal about volume, timbre, and movements. "Haydn," he determined finally. "I don't know which one."

Posted By: Alex - Thu Nov 11, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Human Marvels, Music, 1980s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |