Psychology

The woman who thought she was a chicken

A recent issue of the Dutch journal Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie (Journal of Psychiatry) reports on the case of a woman who believed she was a chicken. From the report (via Google translate):Clinically, we saw a lady profusely sweating, trembling, blowing her cheeks and displaying stereotypical behavior in which she seemed to imitate a chicken, such as clucking, cackling and crowing like a rooster. After ten minutes, she seemed to tense the muscles for a few seconds, her face flushed and she did not respond for a short time. These symptoms repeated at intervals of several minutes, between which anamnesis was possible. The patient's consciousness was fluctuating, attention was hyper-reactive and the patient was disoriented in time and space. Her memory could not be tested objectively, but she could adequately tell her history.

She said she had barely slept since five days and wandered barefoot and dressed in a dressing gown on the street at around 4 a.m. the previous night. A general feeling of unwellness had been present for several days, as well as a strange feeling in the limbs, as if they no longer fit her body and flapped uncontrollably. The patient expressed the thought of being a chicken and that they had been forgotten to roost her.

Patient's brother added that he found her in the garden in the same condition as we saw her now. Between that moment and the registration with us, the bizarre behavior in attacks occurred.

The researchers note that clinical zoanthropy (the belief that one has turned into an animal) is an extremely rare delusion. Apparently there have been only 56 cases of this reported between 1850 and 2012. Some of the animals people believe they have become include "a dog, lion, tiger, hyena, shark, crocodile, frog, bovine, cat, goose, rhinoceros, rabbit, horse, snake, bird, wild boar, gerbil and a bee."

More info: The Guardian

Posted By: Alex - Tue Aug 04, 2020 -

Comments (13)

Category: Animals, Bad Habits, Neuroses and Psychoses, Psychology

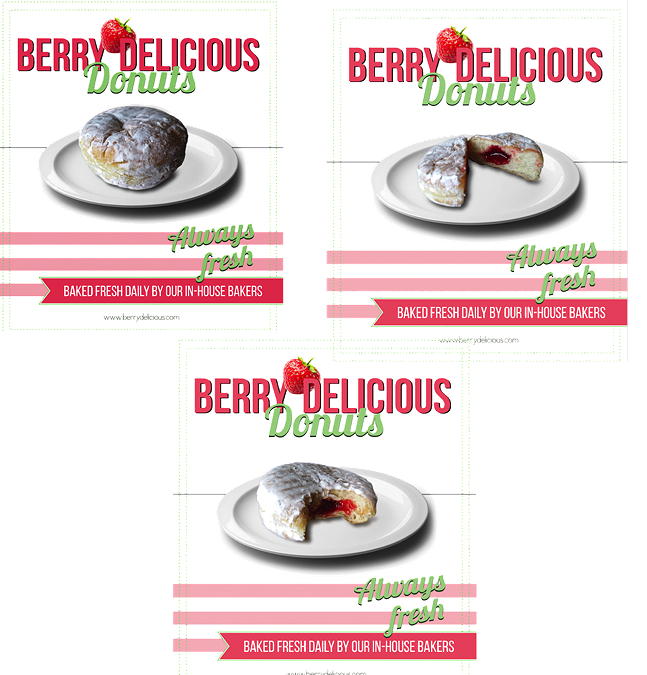

Bitten desserts in advertisements

Do consumers find images of desserts in advertisements more appealing if the desserts are whole, cut, or bitten?The answer: it depends on whether or not the consumer is currently on a diet. That's according to research conducted by Donya Shabgard at the University of Manitoba for her 2017 master's thesis. From the thesis:

These findings explain that the bitten dessert is percieved as more real and authentic in comparison to the cut and whole dessert, and, thus, these perceptions of realness resulted in its positive evaluations. After the bitten dessert, the cut dessert was perceived as being the next most real, with the whole dessert being viewed as the least real of the three.

via Really Magazine

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 02, 2020 -

Comments (0)

Category: Food, Advertising, Psychology, Dieting and Weight Loss

Staring Hitchhikers

Will hitchhikers get more rides if they stare at oncoming drivers or if they look away? A 1974 study published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology attempted to answer this question:In the stare conditions, E stared at the driver of the target vehicle and attempted to fixate on the driver's gaze and maintain this gaze as long as possible until the driver either stopped his vehicle or drove on. In the comparison conditions, E looked anywhere else but at the driver. Thus, on some trials E looked in the general direction of the car; on other trials E looked at his feet, the road, the sky, etc. Es were specifically instructed to neither smile nor frown, and to maintain a casual (neither rigid nor slouching) body postural orientation while soliciting rides.

The two hitchhikers were described as, "both 20 years of age and both dressed in bluejeans and dark coats. The male had short, curly blond hair, and the female, straight, shoulder length blond hair. Both could be described as neat, collegiate, attractive in physical appearance, and of an appropriate age to be hitchhiking."

A hitchhiker in Luxembourg - Aug 1977 (source: wiktionary.org)

(not one of the hitchhikers in the study)

Staring is often interpreted as a threat. So the researchers anticipated that staring at oncoming drivers might result in fewer rides. But the opposite turned out to be true. Which is a useful tip to know if you ever need to hitchhike. But what really helped get a lot of rides was being a single female. From the study:

Contrary to popular belief and hitchhiking folklore , it was no easier for a male-female couple to hitch a ride than a single male, and a mixed sex couple was less successful at soliciting rides than a single female hitchhiker. Although the generality of this conclusion is limited by the fact that it is based upon results obtained by one male and one female E, it is probably the case that couples are less successful hitching rides because of space limitations in the cars they approach. That is, it is more likely that the driver will have room for one additional passenger than that he will have room for two or more additional passengers in his car.

Incidentally, the experimenters never actually ever got in a car with anyone: "After a motorist stopped to pick up one of the hitchhikers, he was politely thanked and given a printed description of the nature of the experiment. No driver expressed any discomfort when he learned that the hitchhiker did not actually want a ride."

Posted By: Alex - Mon May 04, 2020 -

Comments (5)

Category: Science, Experiments, Psychology, 1970s, Cars

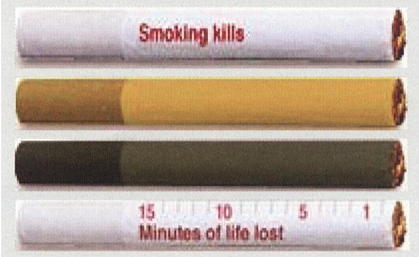

Dissuasive Cigarettes

Public health warnings have been printed on cigarette packs since 1966 (in the U.S.). But recently, public health researchers have been wondering whether altering the appearance of the cigarettes themselves might be more effective. In a study published in the 2016 issue of the journal Tobacco Control, New Zealand researchers tested the response of smokers to a variety of “dissuasive cigarettes.”One of these cigarettes had a “smoking kills” warning printed directly on it. Two others were unpleasant colors: "slimy green" and "faecal yellow-brown." The fourth was printed with a graphic depicting "15 minutes of life lost."

The researchers found that the smokers they surveyed reacted negatively to all four of the dissuasive cigarettes, but had the strongest negative reaction to the "15 minutes of life lost" cigarette:

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jan 28, 2020 -

Comments (2)

Category: Psychology, Smoking and Tobacco

The Zone of Veracity

From the San Francisco Examiner - June 5, 1927:

The latest researches have been made known by Dr. Boris Orlov, a Russian psychologist, now living in Paris. Professor Orlov asserts that modern fashions, by exposing women’s necks, have incidentally exposed their minds. When a woman is not telling the truth, he insists, she will blush in the area just below the breast bone.

Dr. Orlov calls this telltale area the “zone of veracity,” and his book, “La Pseudologie Humaine Normale et Anormale,” offers a number of other interesting tips for the casual detection of untruthfulness. This “zone of veracity,” Dr. Orlov says, is a sort of window through which certain well-disguised feminine mental processes may be seen…

“When a woman lies,” Dr. Orlov continues, “there is inevitably a nervous tension inside her. During the mental stress of lying, this tension is communicated to the vasomotor nerves which control the arteries and capillaries in the skin.

“Blushing in any part of the body is produced by an increased flow of blood into the capillary vessels serving the parts where the blush extends. The area affected is not only reddened, but there is a perceptible increase of heat there.

“The interaction between mind and body is close. A nerve filament from the sympathetic system lies along the sheath of and parallel with each artery and capillary, controlling the expansion and contraction of the muscular coat of the vessel. This is the vasomotor nerve. The mental agitation produced by lying causes temporary vasomotor paralysis and an ensuing rush of blood into the capillary vessels of the skin, which we call blushing.

“A self-controlled deceiver can inhibit blushing in the face. But the feminine fibber’s throat, her upper thoracic area, will visibly palpitate and redden. A throbbing or fluttering will be seen in the area about the breast bone. The blushing will usually cover a space two to three inches in diameter. In many cases, this section of the throat or bosom will redden though not a trace of a blush will color the cheek.”

Posted By: Alex - Thu Jan 09, 2020 -

Comments (3)

Category: Lies, Dishonesty and Cheating, Psychology, 1920s

Chewing Gum Stigma

In Oct 2013, the chewing gum company Beldent gathered five sets of identical twins. In each set, one twin was instructed to chew gum while the other sat motionless. Visitors to the Buenos Aires Museum of Contemporary Art were then asked questions about the twins.Their answers indicated that 73 percent of people had a more favorable impression of the gum chewing twins. Beldent claimed that this disproved the "chewing gum stigma."

Though I disagree. I think gum chewing does turn off some people. What the experiment showed was that there's an even greater stigma attached to being expressionless, showing no emotion at all

Posted By: Alex - Tue Dec 03, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Experiments, Psychology, Candy

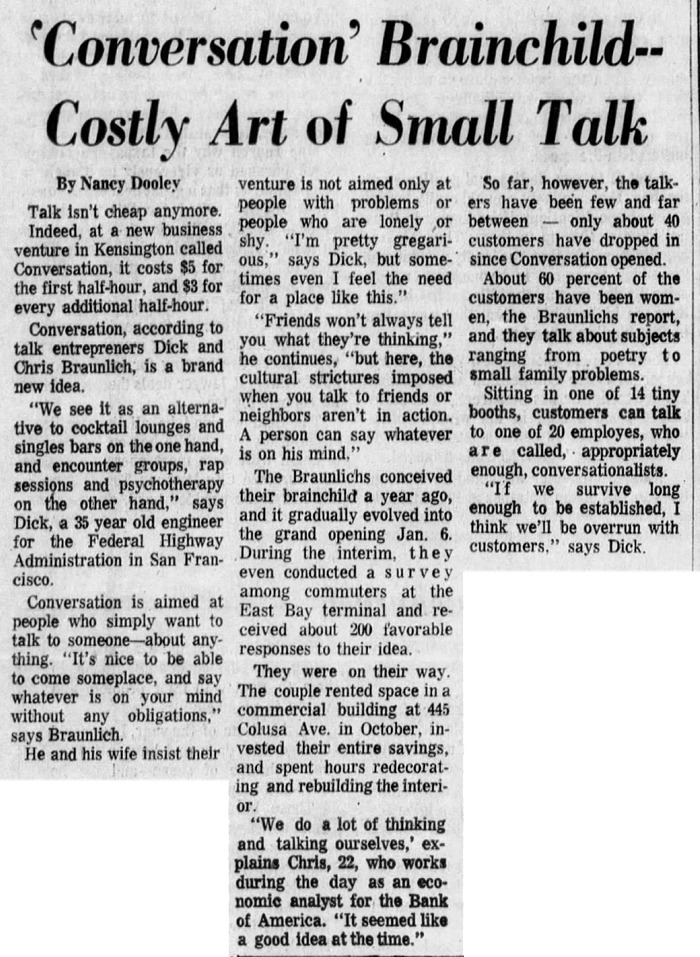

Rent a Conversation

In 1973, entrepreneurs Richard and Christine Braunlich launched a business called Conversation. The idea was that it would allow people to pay to have a conversation with an expert "conversationalist." $5 for the first half-hour, and $3 for each additional half-hour. Some details from the SF Examiner (Feb 11, 1973):So far, however, the talkers have been few and far between — only about 40 customers have dropped in since Conversation opened.

About 60 percent of the customers have been women, the Braunliches report, and they talk about subjects ranging from poetry to small family problems.

Sitting in one of 14 tiny booths, customers can talk to one of 20 employees, who are called, appropriately enough, conversationalists.

And more details from the Moline Dispatch (Feb 13, 1973):

"She left her two kids at a movie and was here when the door opened," he said. "She just wanted to chat with somebody alive, warm and wiggling. Boy, did she want to talk."

Another woman explained that her husband was a nice guy but boring, and she needed to converse with somebody else once in a while...

"Lots of people with problems don't need professional help, but they do need to talk them over," Devendorf said. "They can go to the hairdresser, a bar or a coffee shop, but some are too shy."

At Conversation, persons with serious psychological difficulties are referred to professionals.

Evidently the business didn't succeed.

San Francisco Examiner - Feb 11, 1973

Posted By: Alex - Tue Oct 15, 2019 -

Comments (3)

Category: Business, Jobs and Occupations, Psychology, 1970s

The man hanging from ceiling

Scholarpedia defines inattentional blindness as "the failure to notice a fully-visible, but unexpected object because attention was engaged on another task, event, or object."One of the classic examples of this is provided by the Invisible Gorilla experiment, in which test subjects were asked to watch a video showing a group of people passing a basketball back and forth. Asked to count the number of times the ball was passed, half completely failed to notice that a man wearing a gorilla suit walked through during the middle of the scene.

A recent viral video provides another example. Popular Youtuber Sushi Ramen Riku tied himself to the ceiling of his grandmother's apartment and waited to see how long it would take for her to notice him. Even though he's perfectly visible to her the entire time, in her peripheral vision, she simply doesn't notice him, for over ten minutes. Evidently she didn't expect her grandson to be strapped to the ceiling.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 03, 2019 -

Comments (5)

Category: Video, Psychology

Dessert Stomach

I’ve been saying for years that there’s always room for dessert, because dessert goes to a different part of your stomach. I feel vindicated to find out that there is some scientific basis to this claim. From the Huff Post:"A major part of the reason is a phenomenon known as sensory specific satiety. Basically, this is what we experience when we eat one food to fullness. Our senses tell us we are no longer wanting to eat any more of that specific food. In other words, we are full," Keast told The Huffington Post Australia.

"Part of the response is actually sensory boredom -- the food that excited us with promise of flavour delights is now boring. We are getting satiated, but combine this with the fact that our flavour sensing system is overloaded with the food's flavour helps us stop eating.

"Then you present a dessert, a new flavour experience, a different profile to what we are bored with. It may look and smell good and (from experience) we know sweet is appealing. No more boredom with the food and the anticipation creates appetite -- hence the dessert stomach."

In Japan, this phenomenon is called Betsubara. And some Japanese research suggests that the shape of your stomach can actually change when presented with dessert.

Posted By: Alex - Sat Jul 27, 2019 -

Comments (0)

Category: Food, Psychology

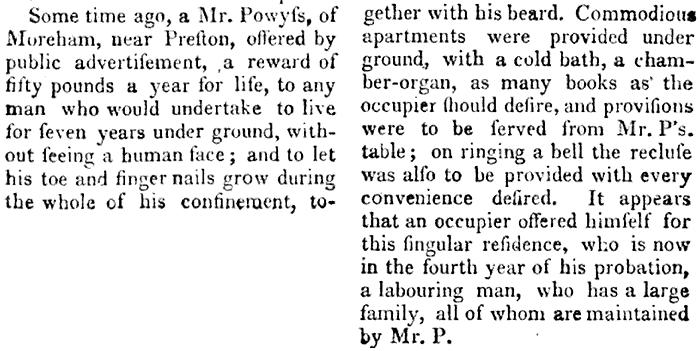

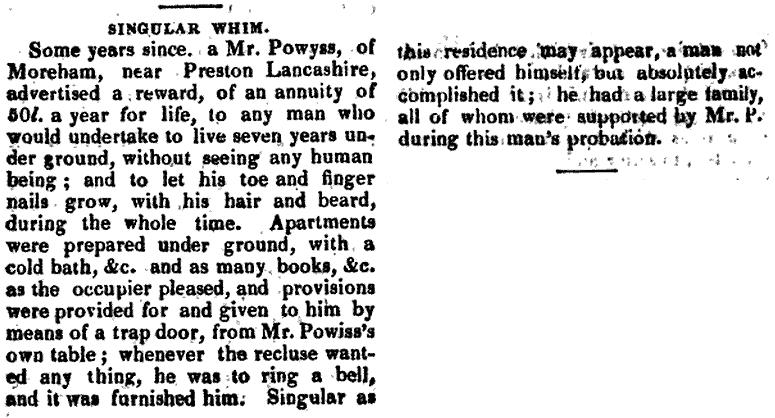

The Solitude Experiment of Mr. Powyss

Circa 1793, a Mr. Powyss of Lancashire apparently decided to conduct an unusual psychological experiment by paying a man to live in his basement, in complete solitude, for seven years.Information about this experiment is hard to find. A brief news item appeared about it in 1797:

The Annual Register... for the year 1797

A news story 30 years later reported that the subject of the experiment had emerged after seven years apparently no worse for wear. Or, at least, he had "absolutely accomplished it":

Given the lack of info, I suspect that the entire story might be an urban legend — one of those fake news stories that often made their way into early magazines and newspapers. However, the story has inspired author Alix Nathan to use fiction to fill in the blanks... imagining what might have happened in her recent novel The Warlow Experiment. As reported by the Guardian:

Posted By: Alex - Fri Jul 19, 2019 -

Comments (3)

Category: Experiments, Psychology, Eighteenth Century

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |