Psychology

Does college turn young women into communists?

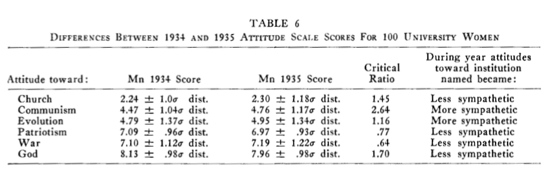

Back in the 1930s families were concerned about whether they should send their young daughters off to college, fearing they might come home infected with communism. So in 1934, psychologist Stephen M. Corey set out to determine whether such fears were justified.Corey administered the Thurstone Attitude Scale to 234 female freshmen at the University of Wisconsin, examining their attitudes with respect to six topics: Reality of God, War, Patriotism, Communism, Evolution, and Church. A year later he retested 100 of these students when they were sophomores.

Godless communists?

When he presented his findings at the Midwestern Psychological Association convention in May 1940, he assured everyone that it was safe to send young women to college, saying, "There was no great difference in the girls' attitudes. The average co-ed apparently would rather mix with stag lines than picket lines."

He also emphasized that the young women lost none of their feminine habits at college. A United Press reporter paraphrased his words:

However, if you look at his 1940 article in the Journal of Social Psychology*, in which he published the results of his study, you find somewhat different information. There he revealed that after a year at college the attitudes of the young women did change slightly, but consistently, in the direction of liberalism — which is to say that they showed less sympathy for god, war, patriotism, and the church, and more sympathy for communism and evolution.

Corey wrote in that article, "The opinions of the students appeared to have undergone at least a degree of liberalization during their one year of attendance at a University."

I guess he wasn't actually lying to the folks at the Midwestern Psychological Association. It's all how you choose to spin the data.

San Bernardino County Sun - May 5, 1940

* Corey, S.M. (1940). "Changes in the opinions of female students after one year at university." The Journal of Social Psychology, 11: 341-351.

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 17, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Psychology, 1930s, Women, Universities, Colleges, Private Schools and Academia

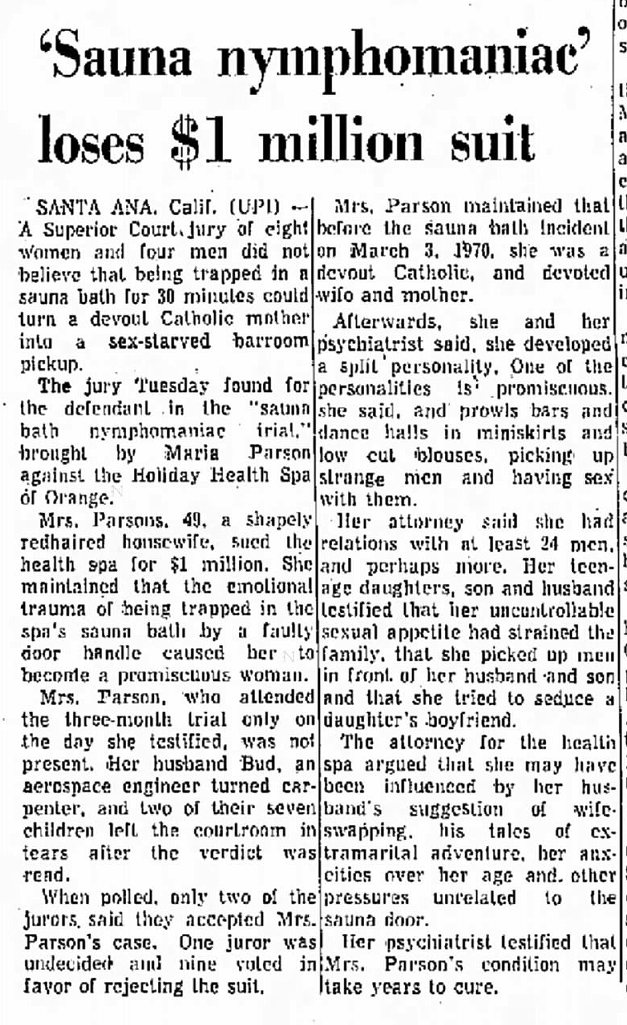

The Sauna Bath Nymphomaniac

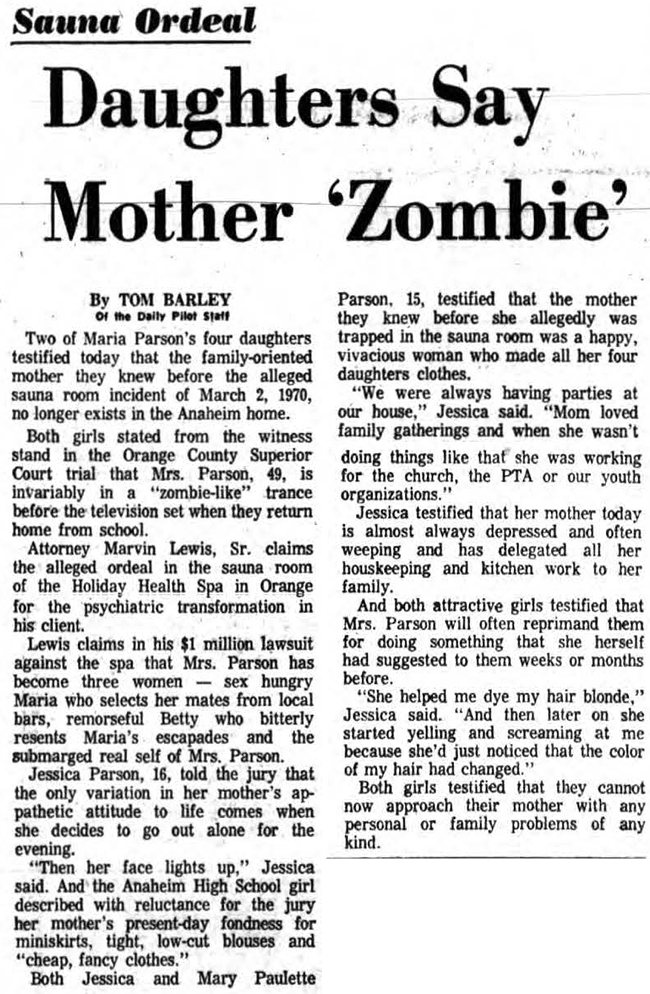

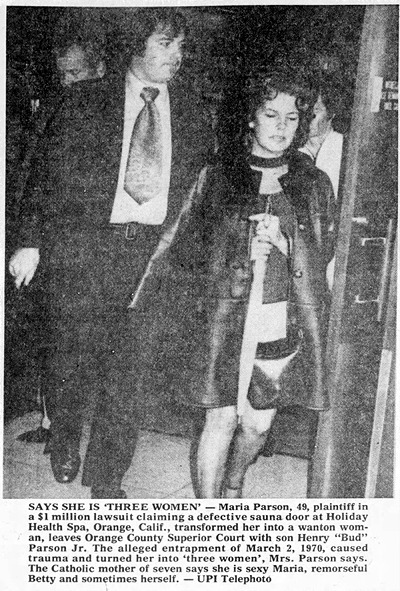

The case of the cable car nymphomaniac is a classic weird news story. Less well known, but along similar lines, is the case of the sauna bath nymphomaniac.Maria Parson claimed that the trauma of being accidentally locked in a sauna for half-an-hour due to a faulty door handle caused her to develop a split personality. She came to have three personalities: "sex-hungry Maria" who prowled bars picking up men, "remorseful Betty" who bitterly resented Maria's escapades, and her submerged real self.

She sued the health spa for $1 million, but lost — even though she was represented by the same lawyer who had secured a win for the cable car nymphomaniac.

Orange Coast Pilot - Dec 20, 1973

Bellingham Herald - Jan 10, 1974

Eureka Times Standard - Mar 6, 1974

Posted By: Alex - Wed Apr 20, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Lawsuits, Psychology, 1970s, Sex

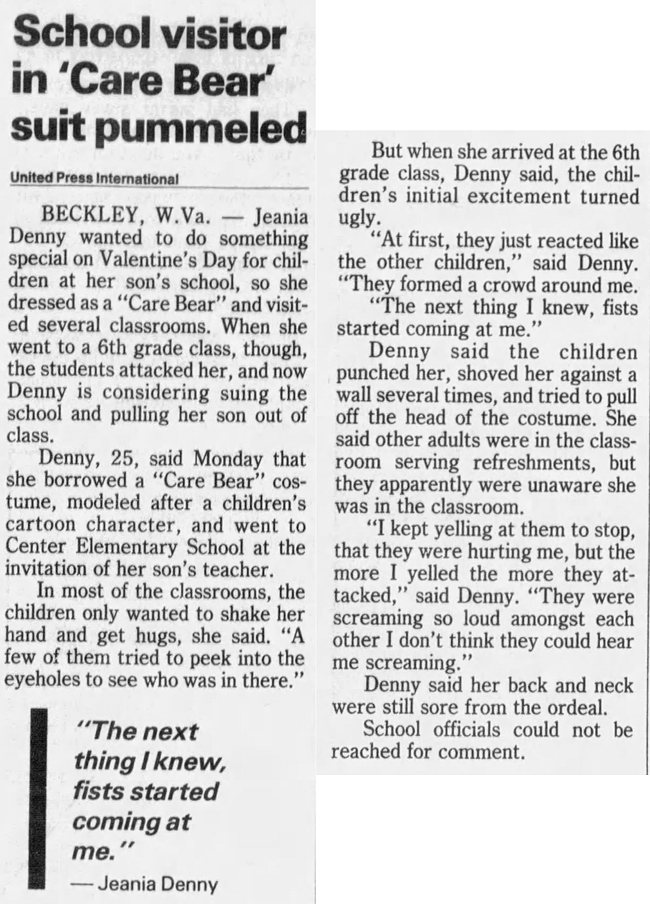

Care Bear Abuse

Feb 1987: Wanting to do something special for her son, Jeania Denny wore a Care Bear costume to his school on Valentine's Day. However, she soon found herself being violently attacked by a crowd of sixth-graders. Said Denny, "I kept yelling at them to stop, that they were hurting me, but the more I yelled the more they attacked."I've heard reports of children (and adults) at Disney theme parks hitting the costumed characters, which seems similar to what happened to Jeania Denny. In the minds of the children, the costume must dehumanize the wearer, which then makes it seem okay to hit them.

Tampa Bay Times - Feb 17, 1987

I'm guessing this was the type of costume that Denny was wearing:

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jan 30, 2022 -

Comments (6)

Category: Violence, Psychology, 1980s

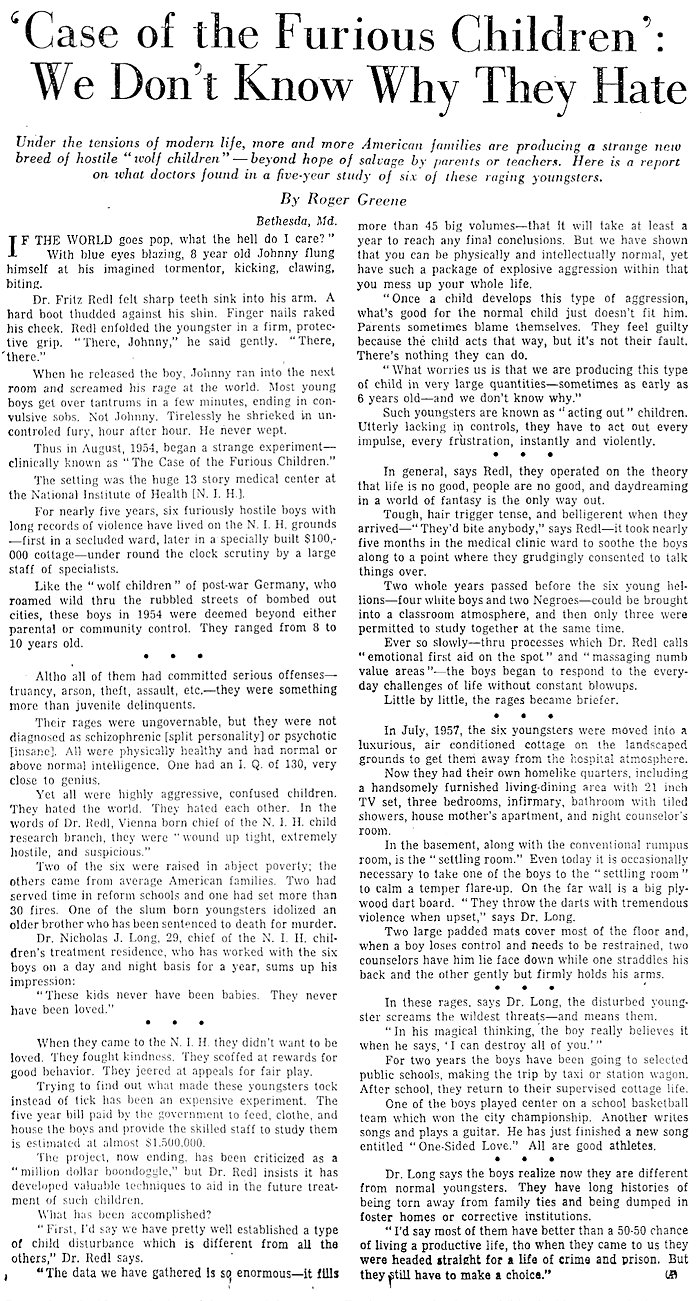

The Case of the Furious Children

In 1954, six young boys who exhibited violent behavior were brought to live on the grounds of the National Institute of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. They were specifically selected because they were deemed the worst of the worst:For the next five years, the boys were attended around the clock by a team of specialists.

It was all part of an experiment, which came to be known as the "Case of the Furious Children," designed to find out why these young boys were so violent and whether they could be turned into responsible citizens. Eventually, around $1.5 million (in 1950's dollars) was spent on this effort.

By the end of the experiment, one of the researchers, Dr. Nicholas Long, said that the boys now had a "better than 50-50 chance of living a productive life." So what became of them? Were they reformed, or did they head down the path of crime and prison that they originally seemed to be destined for?

I'd be interesting to know, but I haven't been able to find anything out. I'm guessing the info has never been released because of privacy issues.

More info: Harpers Magazine - Jan 1958

Chicago Daily Tribune - July 19, 1959

Posted By: Alex - Wed Jan 19, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Antisocial Activities, Experiments, Psychology, Children, 1950s

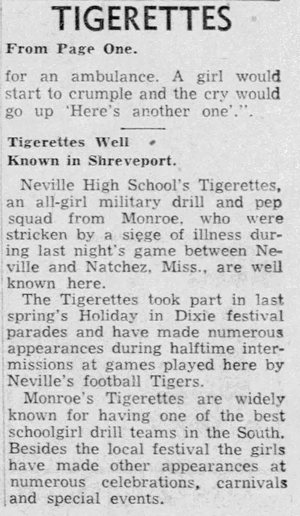

The Fainting of the Tigerettes

Sep 12, 1952: At the end of the first quarter of a high-school football game in Natchez, Mississippi, the 165 members of the Tigerettes cheerleading squad mistakenly marched onto the field to perform their halftime routine. Made aware of their mistake, the cheerleaders began to faint. All of them. One after another. A witness described them as "dropping out like flies". It remains one of the largest mass-fainting events in history.

Shreveport Journal - Sep 13, 1952

The Tigerettes

Monroe Morning World - Apr 27, 1952

Posted By: Alex - Thu Dec 09, 2021 -

Comments (1)

Category: Crowds, Groups, Mobs and Other Mass Movements, Psychology, 1950s

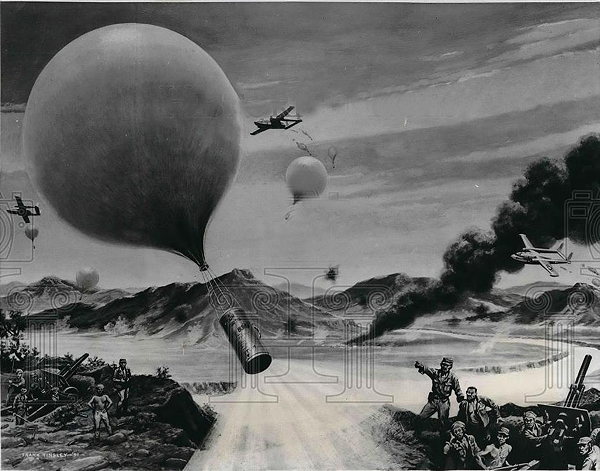

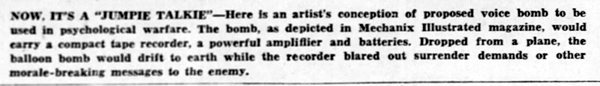

The Voice Bomb

This is another example of the military's interest in using sound to demoralize the enemy. This device was rather straightforward: "Dropped from a plane, the balloon bomb would drift to earth while the recorder blared out surrender demands or other morale-breaking messages to the enemy."See also: Weird alien sounds designed to terrify and panic, and Ghost Tape Number Ten

The Pantagraph - Oct 12, 1951

Posted By: Alex - Tue Sep 07, 2021 -

Comments (4)

Category: Psychology, 1950s, Weapons

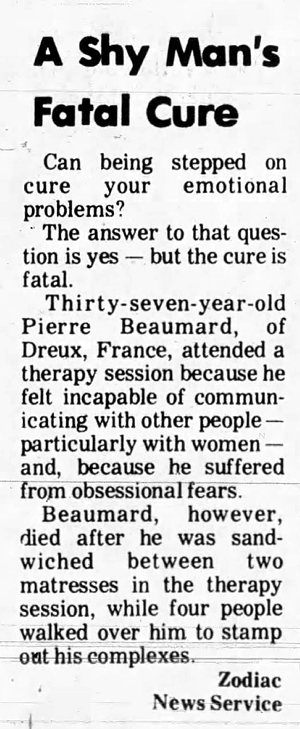

The Death of Pierre Beaumard

1979: To help cure his shyness around women, Pierre Beaumard's therapist had him lie sandwiched between two mattresses. This was meant to simulate the womb. Four people then walked on top of the mattresses to "stamp out his complexes". Beaumard died of suffocation.I'm skeptical about whether this story is true. For some reason it makes my BS spidey sense tingle. It was definitely reported in papers as legitimate news, but it's been known to happen that reporters will hear an urban legend or joke and then (knowingly or not) put it out on the wire services as a true story. I'm suspicious that's what happened here. I'd believe it more if I could find an original French source, which I can't.

The Santa Clarita Signal - May 27, 1979

The Ottawa Citizen - May 17, 1979

Posted By: Alex - Sun Sep 05, 2021 -

Comments (2)

Category: Death, Psychology, 1970s

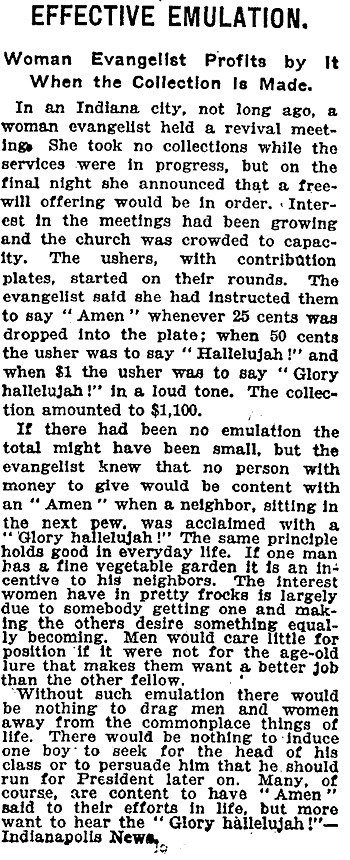

Effective Emulation

A simple, psychological trick maximizes church giving:the evangelist knew that no person with money to give would be content with an "Amen" when a neighbor, sitting in the next pew, was acclaimed with a "Glory hallelujah!"

New York Times - May 18, 1919

Posted By: Alex - Wed Aug 18, 2021 -

Comments (3)

Category: Money, Religion, Psychology

Swindle’s Ghost

'Swindle's Ghost' is a term for an optical illusion that some psychologists have offered as a possible scientific explanation for ghost sightings. Actually, I doubt that many sightings are a result of this phenomenon, but I like the name.Newsday Special Correspondent Paul Brock (May 15, 1967) offered this explanation:

It can be summoned up by anybody. Using no more ectoplasm than a table lamp, friends can join you in this weird experiment, right in your own living room. Choose a dark moonless night and draw the drapes securely so that no stray light from street lamps or passing cars enters the room. Group the chairs near a table or floor lamp with one person directly alongside it to switch it on and off.

First, everyone must remain in the darkened room for at least 10 minutes before the experiment begins, so that the eyes can adjust completely to the darkness. Then, each ghosthunter must look steadily toward the lamp but not directly at it. They must keep perfectly still and keep the eyes from moving during the time the room will be illuminated and immediately afterward.

Now turn on the lamp for a full second. Turn it off. Shortly after you will see the whole scene loom up in the darkness with startling clarity, and the ghost impression will last for some time. Not only will everything appear exactly as it was when the light was on, but many precise details will be evident which could not possibly have been noted during the brief illumination...

The same optical illusion occurs when someone reports that he has seen a ghost in a graveyard at night. If a man is passing a graveyard at night and the moon breaks through the clouds just as he is opposite a white tombstone, in a few minutes he might see a vague white form loom up before him. The moon's illumination has created the 'ghost' which the man actually does see, but which is only an after-image— in the image of "Swindle's Ghost."

Some more info in the book Systems Theories and A Priori Aspects of Perception:

You can find Swindle's original article here:

Swindle, P.F. (1916). Positive Afterimages of long duration. American Journal of Psychology, 27, 325-334.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Jun 15, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Paranormal, Supernatural, Occult, Paranormal, Psychology, Eyes and Vision

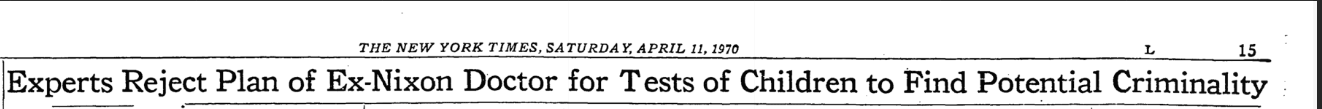

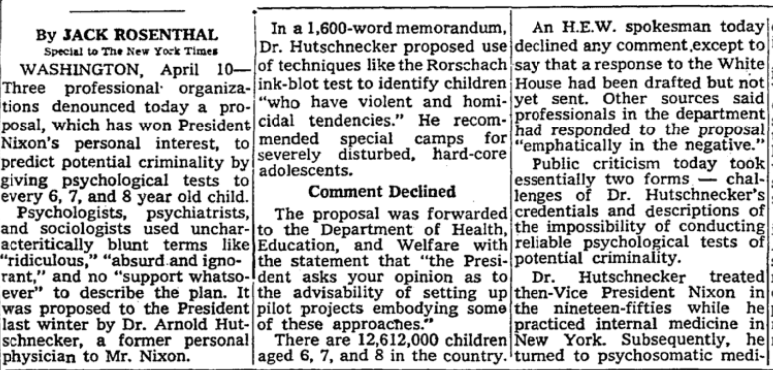

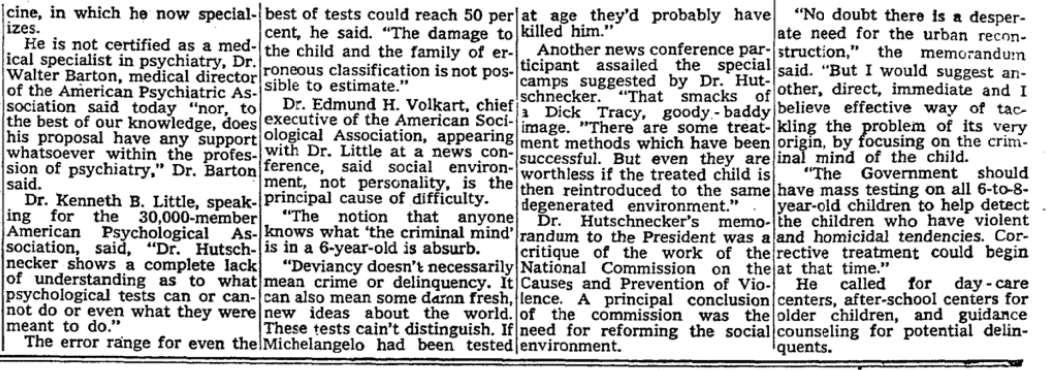

Arnold Hutschnecker’s Juvenile Criminality Tests

His Wikipedia page is here.Not mentioned is the legal charge at age 89 of seducing a patient.

Interesting details of his relationship with Richard Nixon in this obit.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Apr 24, 2021 -

Comments (0)

Category: Crime, Psychology, Children, 1970s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |