Architecture

The Paper House

I think that hoarding newspapers used to be very common. I base this assumption on the fact that I know of two Depression-era relatives in my extended family who never threw away newspapers and ended up with stacks of them in their house. And if I had two in my family, I'm guessing many other families also had paper hoarders.Elis F. Stenman of Pigeon Cove, Massachusetts put his paper hoarding habit to good use by constructing his house, and all the furniture in it, out of the newspapers he refused to throw away. The house still exists and is open to the public.

Of course, now that newspaper deliveries are becoming a thing of the past, paper hoarding must be on the decline.

Images from The Pittsburgh Press - Sep 8, 1938.

Posted By: Alex - Tue Feb 21, 2023 -

Comments (4)

Category: Architecture, Newspapers

Blast-Resistant House

Posted By: Alex - Fri Dec 30, 2022 -

Comments (1)

Category: Architecture, Advertising, Atomic Power and Other Nuclear Matters, 1950s

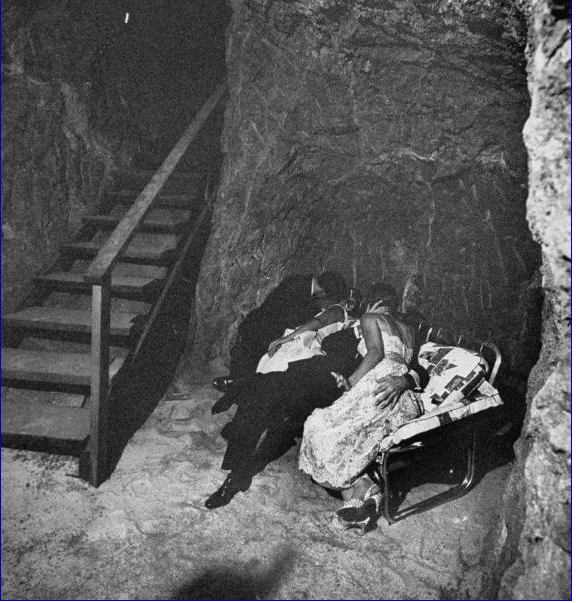

Hal Hayes’s Swinging Bachelor Mansion

For $600,000 -- adjusted for inflation, about $4.9 million today -- Hayes got a six-level, steel-and-glass pad with masculine, maximum technology and minimal custom decoration. He parked on girders projecting from the edge of his hillside lot, piped in hi-fi music, poured drinks from an ultra-sleek mini kitchen designed for catering, not for cooking, seduced brunettes in an orchid greenhouse and did what bachelors do in a free-standing “playroom.”

There was a circular fireplace, a louvered skylight, a mirrored master suite and an artificial beach for topless tanning. An outdoor hearth in gunite lava rock warmed women chilled by gin martinis.

Guests in the bomb shelter of Hal Hayes's house.

Retrospective write-up at the LA TIMES.

1958 feature in LIFE magazine.

Some great pix with this article.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Dec 26, 2022 -

Comments (4)

Category: Architecture, Domestic, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Space-age Bachelor Pad & Exotic, 1950s

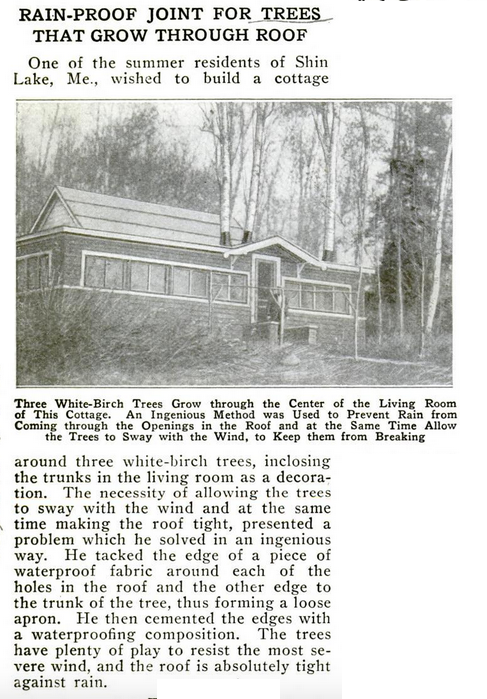

Houses Integrated with Trees

I once ate at a restaurant in Medellin, Colombia, which featured a massive tree in the dining area that grew up through the roof. The urge to blend trees with houses is an ancient one.Here's an instance from 1920.

This article details modern occurences of the motif.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Dec 12, 2022 -

Comments (0)

Category: Architecture, Domestic, Nature, 1920s

Underground Smog Shelter

Despite living on a hill that was relatively free of smog, millionaire Bill Bounds built an underground smog shelter where he could "breathe air filtered by activated charcoal."

"Bill Bounds at the entrance to his underground smog shelter"

Lansing State Journal - Dec 5, 1971

Posted By: Alex - Fri Nov 18, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Urban Life, 1970s

Dome living

I imagine a house like this might be possible to build nowadays, but the monthly electric bill would be a small fortune.

Related post: The Winooski Dome

Posted By: Alex - Sat Oct 29, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Utilities and Power Generation, 1950s, Yesterday’s Tomorrows

Louis Duprey’s Trapdoor Theater Seats

One of the minor annoyances of going to a theater is having your view blocked if someone in front of you gets up from their seat. Or having to stand from your seat to let someone get by.Back in 1924, Louis Duprey patented a solution to this problem. He envisioned a theater in which guests would enter through a subchamber, get into their seats, and then be raised upwards by a hydraulic lift, through a trapdoor, into the theater itself. Anyone who wanted to leave early could simply lower themself back down, disturbing no one else.

It's an over-engineered solution to a minor problem, but I would happily pay extra, at least once, to experience a theater like this. Though I'd probably spend the entire time going up and down in my chair.

More info: Patent No. 1,517,774

Related Posts: Thomas Curtis Gray's horizontal theater, Theater in a Whale, Lloyd Brown's Globe Theater

via New Scientist

Posted By: Alex - Thu Oct 20, 2022 -

Comments (6)

Category: Architecture, Entertainment, Theater and Stage, Patents, 1920s

Lavaforming

Icelandic architect Arnhildur Palmadottir has proposed creating buildings (and entire cities) out of lava. From her website:The basic idea is to create trenches and forms to direct the flow of the lava. Then just wait for the volcano to erupt and hopefully flow in the intended way.

More info: Surfaces Reporter

Update: Paul tells me that the Santa Maria Church in Randazzo, Sicily was built with black lava stones.

Posted By: Alex - Sun Jul 31, 2022 -

Comments (2)

Category: Architecture

Coral Castle, Florida

Their homepage.Their Wikipedia entry.

Posted By: Paul - Sat Apr 30, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Eccentrics, Regionalism, Statues, Monuments and Memorials, North America, Twentieth Century

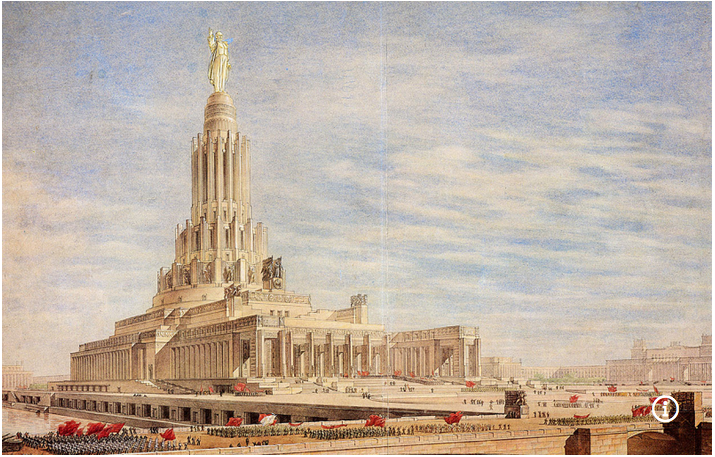

The Palace of the Soviets

Take what metaphors and allegories you will from this famous failure.

The Wikipedia page tells us:

The Palace of the Soviets (Russian: Дворец Советов, Dvorets Sovetov) was a project to construct a political convention center in Moscow on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. The main function of the palace was to house sessions of the Supreme Soviet in its 130-metre (430 ft) wide and 100-metre (330 ft) tall grand hall seating over 20,000 people. If built, the 416-metre (1,365 ft) tall palace would have become the world's tallest structure, with an internal volume surpassing the combined volumes of the six tallest American skyscrapers.[10]

The music on this video is annoying--hit MUTE--but otherwise it's well done.

Posted By: Paul - Fri Apr 15, 2022 -

Comments (3)

Category: Architecture, Excess, Overkill, Hyperbole and Too Much Is Not Enough, Government, Success & Failure, Russia, Twentieth Century

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |