Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil

Eclectric Oil

Dr. Thomas' Eclectric Oil was widely sold as a cure-all in the second half of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. This was even though, as Wikipedia notes, it "mostly contained common ingredients such as turpentine and camphor oil."Some of the things it supposedly cured included rheumatism, lame backs, sore throats, coughs and colds, throat and lung disease, and asthma. It could even cure "chicken flesh wounds" (see ad below).

Wikipedia notes that the name Eclectric Oil was "likely a portmanteau of the words 'eclectic' and 'electric', alluding to the then-popular belief that electricity had curative powers." Of course, the oil was not electric in any way.

image source: wellcome collection

Canadian Poultry Review - Apr 1926

Posted By: Alex - Sun Apr 07, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Nineteenth Century

Cancer Cured with soothing balmy oils

McClure's Magazine - Apr 1898

Posted By: Alex - Fri Feb 23, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Nineteenth Century

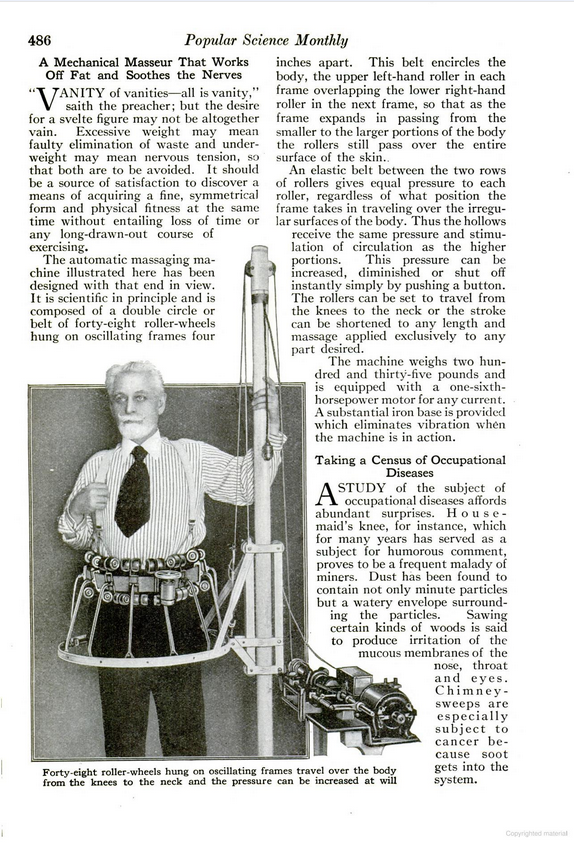

The Fat Roller

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Sun Feb 04, 2024 -

Comments (3)

Category: Body Modifications, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1910s

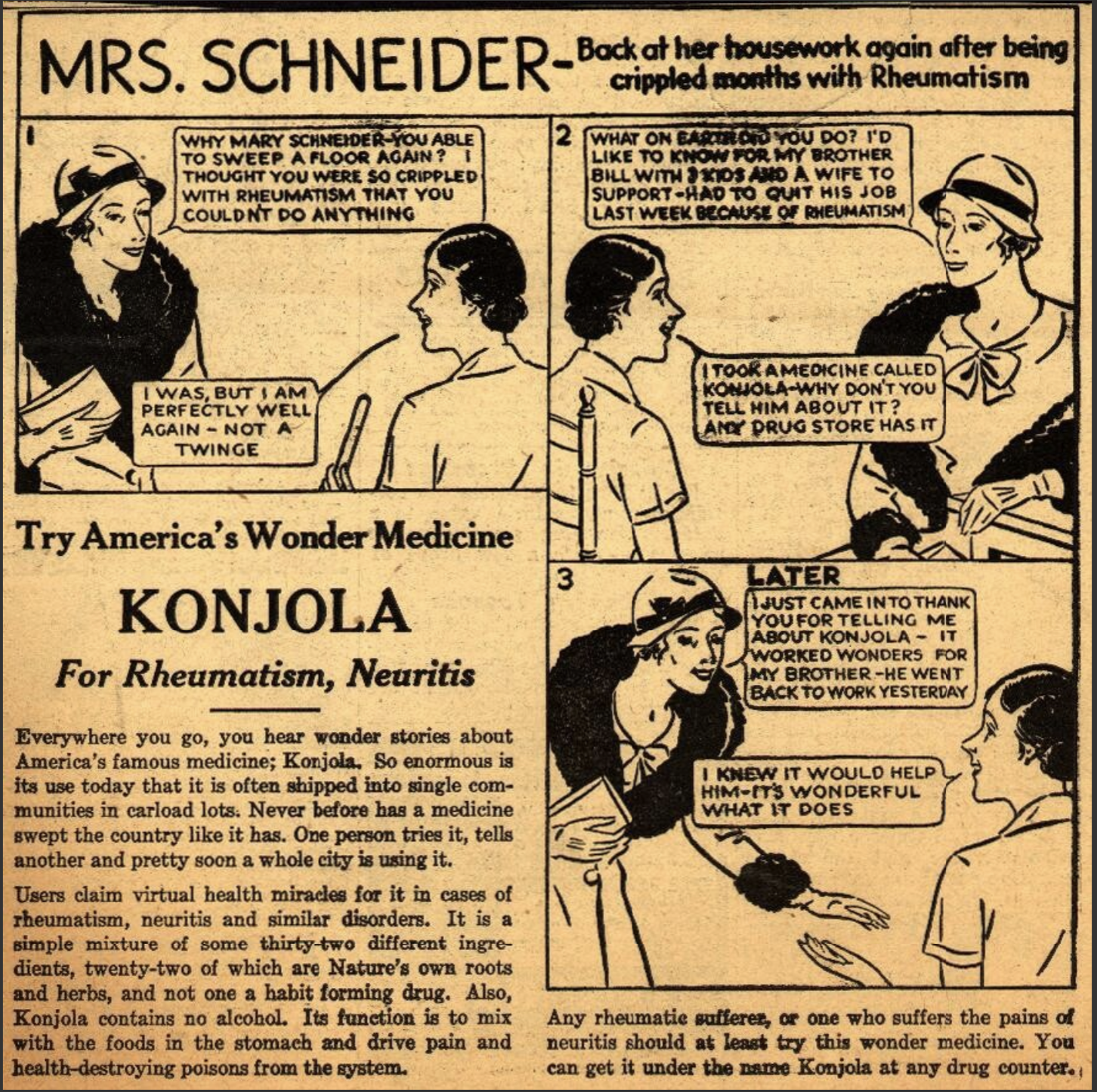

Konjola

Read the full story here.It was a vegetable concoction with a high alcohol content that could be sold without prescription and gave comfort to many who could not or would not find a bootlegger to ease the strictures of Prohibition.

Konjola sold like bathtub gin in the Roaring Twenties. Gilbert and Roberta started Mosby Medicine by mixing up tubs of Konjola in their basement and bottling it themselves. By 1927, Mosby owned a factory on Reading Road in Avondale and was planning an even bigger complex up the road. Mosby bought a spectacular neon sign, 84 feet long and 32 feet high, to advertise Konjola on the central pier of the Atlantic City boardwalk.

And then it all fell apart.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Jan 29, 2024 -

Comments (2)

Category: Regionalism, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1920s, Alcohol

Follies of the Madmen #586

Posted By: Paul - Fri Jan 26, 2024 -

Comments (0)

Category: History, Advertising, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1960s

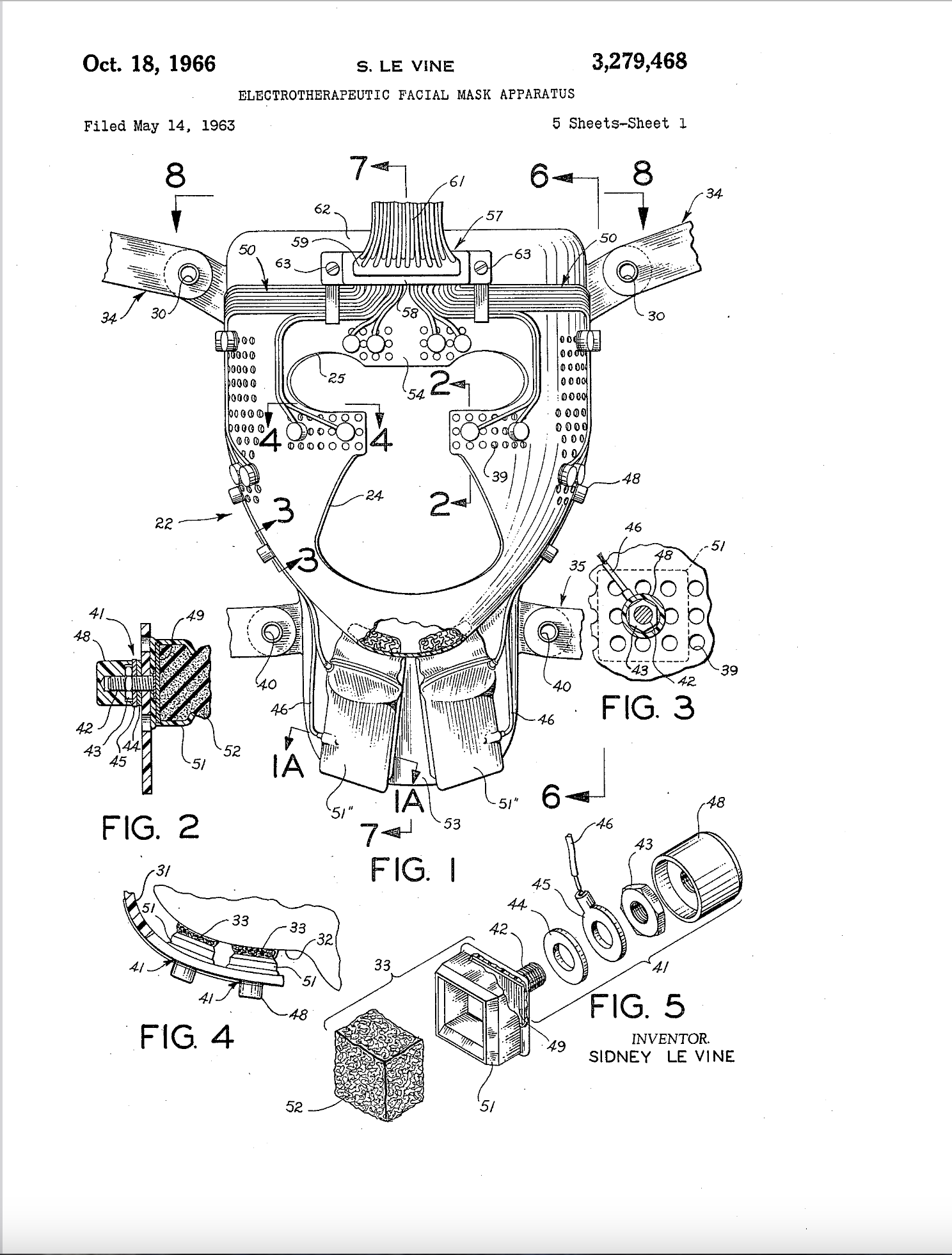

Electrical Stimulation Face Mask

Full patent here.

Posted By: Paul - Wed Dec 06, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Frauds, Cons and Scams, Technology, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1960s, Face and Facial Expressions

Mental Magnetism

Read it here.

Posted By: Paul - Mon Oct 30, 2023 -

Comments (5)

Category: New Age, Supernatural, Occult, Paranormal, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, Books, 1920s

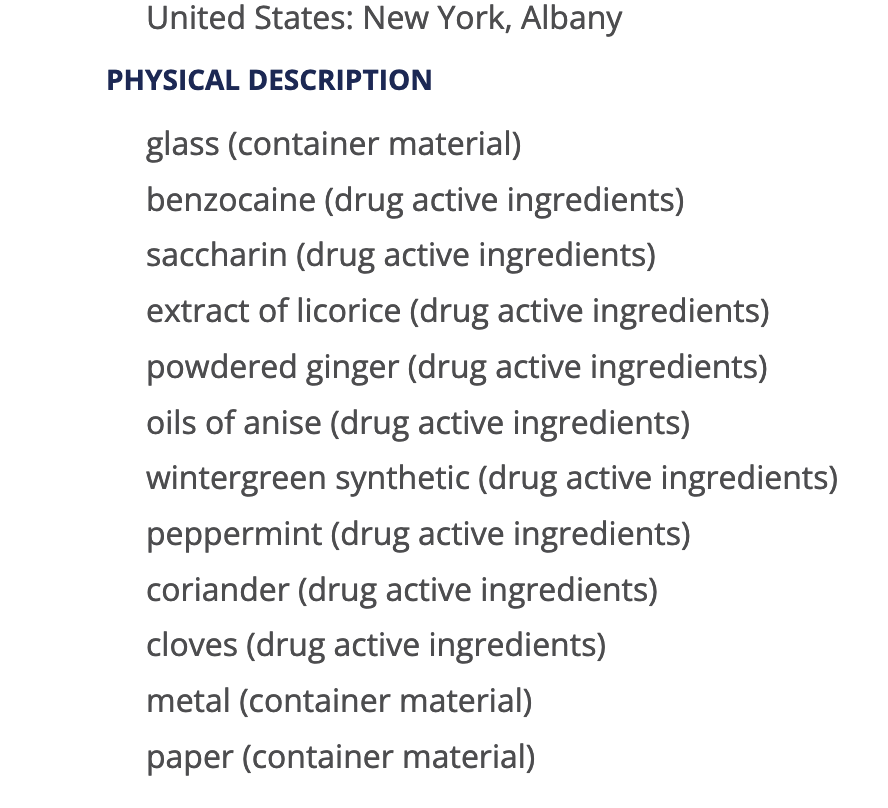

Flavettes

What were the miracle ingredients that could cure the tobacco habit?

Source.

Posted By: Paul - Tue Oct 24, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Scams, Cons, Rip-offs, and General Larceny, Tobacco and Smoking, Advertising, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1950s

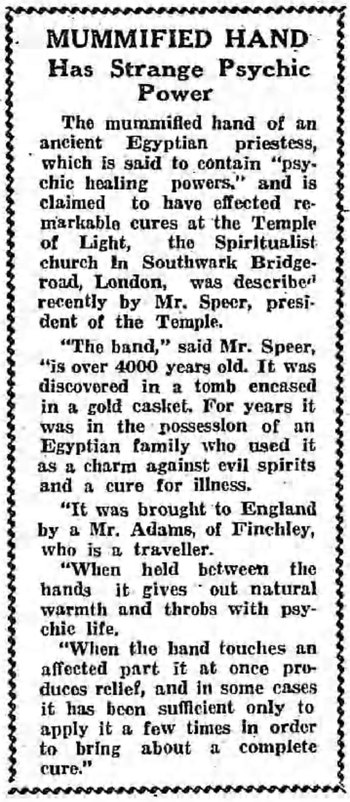

Healing Mummified Hand

Although the mummified hand supposedly healed 500 people, I've only been able to find one description of a "cure":

Saskatoon Phoenix - Feb 8, 1928

Sydney Sunday Times - Feb 5, 1928

Posted By: Alex - Tue Sep 12, 2023 -

Comments (1)

Category: Paranormal, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1920s

Breathing Balloon

"will develop your form, if that's what you want".

Mechanix Illustrated - Sep 1949

Posted By: Alex - Sat Aug 05, 2023 -

Comments (0)

Category: Beauty, Ugliness and Other Aesthetic Issues, Inventions, Patent Medicines, Nostrums and Snake Oil, 1940s

| Who We Are |

|---|

| Alex Boese Alex is the creator and curator of the Museum of Hoaxes. He's also the author of various weird, non-fiction, science-themed books such as Elephants on Acid and Psychedelic Apes. Paul Di Filippo Paul has been paid to put weird ideas into fictional form for over thirty years, in his career as a noted science fiction writer. He has recently begun blogging on many curious topics with three fellow writers at The Inferior 4+1. Contact Us |